Local S6 & the Spirit of the CIO: Welders Wage Wartime Wild Cat Strikes

PHOTO: Two of the seven Bath Iron Works destroyers transferred to the Royal Navy in the Destroyers for Bases Agreement. The outboard ship made the St. Nazaire Raid. Photo by C.J. Ware, Royal Navy official photographer.

In the spring of 1943, Bath Iron Works was humming with activity as nearly 12,000 men and women worked day and night to build warships to defeat the Nazis in Europe and the Japanese in the South Pacific. By June 28, 1943, the company launched its eleventh destroyer of the year, the Ingersoll, in a ceremony that included British Ambassador Lord Halifax, Under Secretary of the Navy James Forrestal and numerous other dignitaries, diplomats and Navy bigwigs. After the Ambassador inspected the ships at the yard, he passed the evening as guests of BIW President William Newell and his wife.

“One thing is certain," wrote the Bath Daily Times of the event, "the reputation which Bath has made down through the years for building ships, whether for cargo carrying, pleasure craft or naval service, has gained rather than deteriorated and with the frequency with which we are launching naval craft, about two weeks apart, we certainly feel that we are doing our bit toward winning the war."

On the surface, labor relations appeared to be running smoothly with the 1941 victory of the company-friendly Independent Brotherhood of Shipyard Workers over the more militant CIO affiliate, the International Union of Marine and Shipbuilding Workers (IUMSWA). The Independent Brotherhood’s success helped pave the way for other shipyard workers up and down the east coast to go independent. Jim Harkins, the founder and first president of the Independent Brotherhood at BIW, was instrumental in founding the “East Coast Alliance of Independent Shipyard Unions of America,” an alternative to the warring AFL and CIO factions.

In February of that year, the pro-business Lewiston Sun Journal applauded the Independent Brotherhood for working collaboratively with BIW. The editor contrasted the labor climate in Bath to Detroit where 6500 UAW workers in the gear and axle division of General Motors broke a wartime “no strike pledge” and walked out in a dispute over the rate of production of certain parts. The LSJ blasted the CIO autoworkers for allegedly stopping the production of army jeeps while the Independent Brotherhood in Bath brought its concerns about wages, sick leave, vacation pay, lunch breaks and other contract disputes to the War Board’s Shipbuilding Commission.

“Even though the contract was not renewed in June because of differences, the workers at the Bath Iron Works stayed on their war job of turning out destroyers for the Navy,” the editorial continued. “Apparently they believe as this column has maintained that no strike can be justified now regardless of what the circumstances may be, for our nation is engaged in a gigantic war which demands of industry’s wheels.”

But not everyone was happy and contented among the men and women who built the ships. Many shipbuilders, especially the welders, felt that the Independent Brotherhood was not doing a good a job representing their interests and easily caved to company demands.

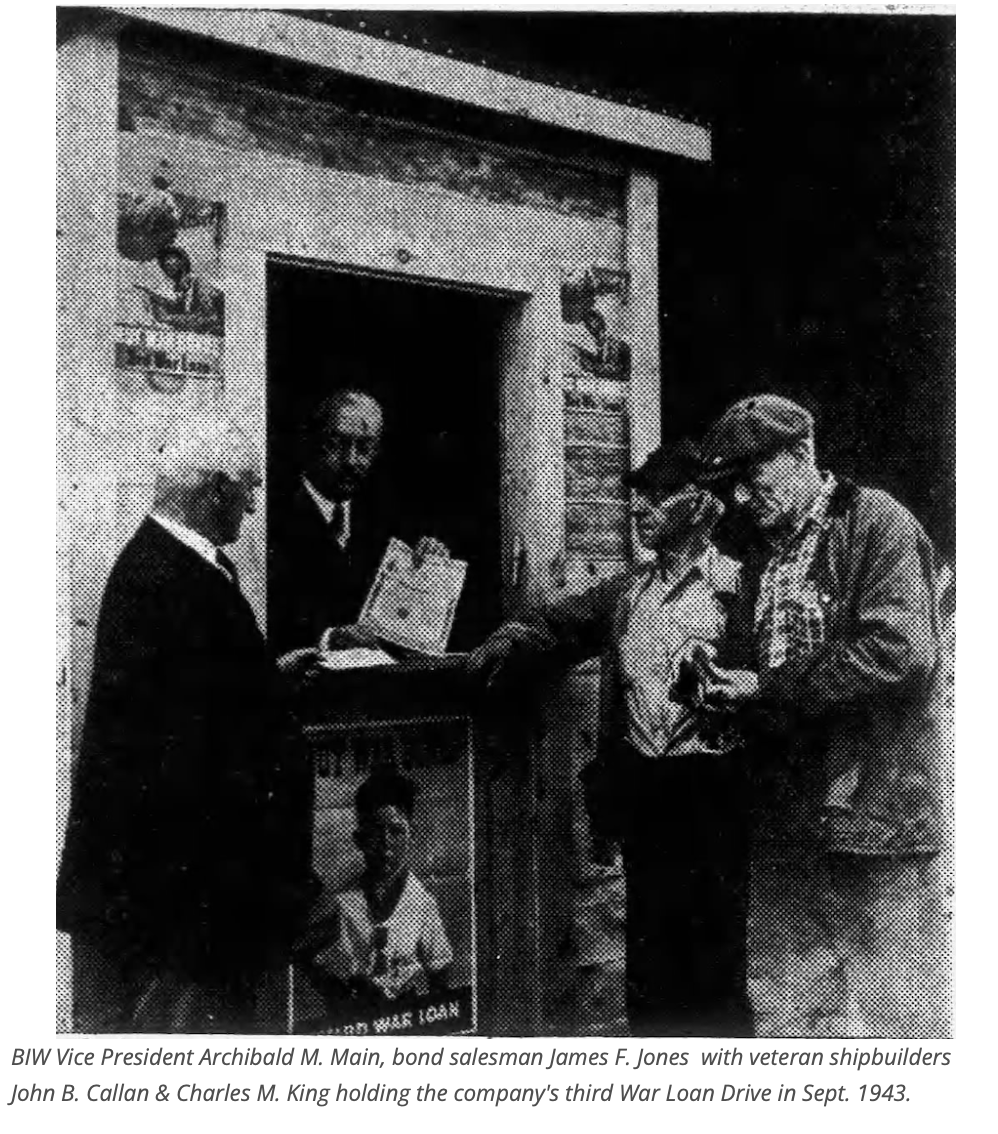

Despite President Roosevelt's famous denunciation of war profiteers on the campaign trail in 1936, defense industry profits were soaring at the height of World War II. In 1942, the House Naval Affairs Committee singled out Bath Iron Works among a handful of other defense contractors for raking in “excessive and unconscionable” profits. The committee report found that BIW had earned profits of $850,000 to $1.13 million ($15 to $20 million adjusted for inflation), 8 to 29 percent, on eight contracts. The following year, in 1943, BIW hauled in a record $3.7 million profits, roughly $64,681,000 in today's money.

Shipbuilders saw those figures and wondered why they weren’t getting their fair share of these lucrative contracts. CIO supporters hoped to finally win an election with the more militant IUMSWA so they could take on the company. However, out of 9,000 eligible voters, the Independent Brotherhood ended up once again crushing IUMSWA, 5,072 to 2,111, with 294 workers choosing the AFL and 59 voting ‘no’ to all three unions.

The Strike Summer of '44

In spite of their losses, the radical CIO welders continued to be a thorn in the side of both the company and the leaders of the Independent Brotherhood. From the summer to the fall of 1943, the shipyard was rocked by a series of unauthorized wildcat strikes.

On May, 31, 240 welders on the night shift walked out after the demotion of a few supervisors and the dismissal and suspension of a welder after a party. The company responded that it would reinstate the welder with a warning and that the other cases were “under discussion.” The strike ended with an ultimatum for the welders to return to work as they had violated the union's "no strike" clause. The Independent Brotherhood placed the blame on CIO sympathizers for stoking the unrest while CIO representatives said that, far from supporting the strike, the union was doing all it could to get the strikers to go back to work.

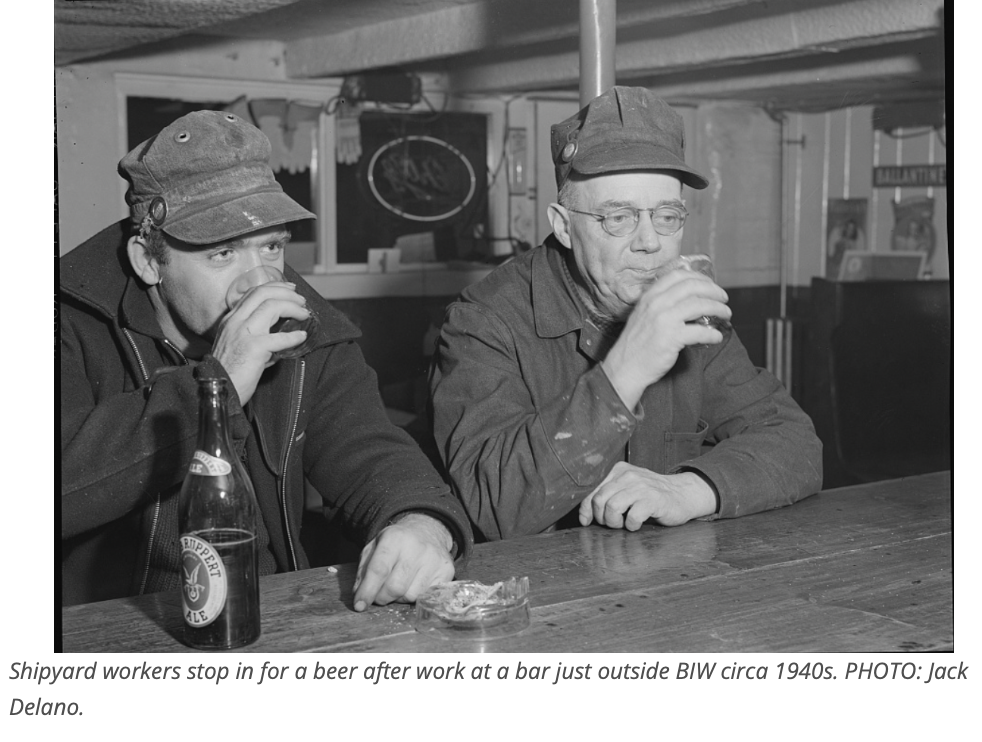

Then in mid-August, another 150 welders walked out to protest being reassigned to the 4pm to midnight shift without their consent or regard to seniority. The wartime walkouts were condemned by local newspapers and prominent men in the community. Father Timothy C. Maney at St. Mary’s Catholic Church in Brunswick “soundly berated” the strikers in a Sunday sermon. He contrasted their behavior with a local man named Bobby Hawks, who had been serving on the frontlines “calmly and uncomplainingly” accepting “24 hour jobs that might bring death at any moment.”

While the welders drew “high salaries” of $18 dollars a day and complained about their long hours, wages and scheduling, he continued, “the American boys, on the fighting fronts, were the only ones who had the privilege to complain, but you never heard anything from them.” He didn't mention the massive profits President Newell and his shareholders were raking in.

“Look at Bobby Hawks,” said Father Maney, not realizing Hawks himself was sitting in the pews. “For three years he has been in the fight. He’s been up and down the Pacific, in the thick of things. You didn’t hear anything about his working too long hours, about the poor pay he was receiving, about how he’d like a change in schedule. You haven’t heard of him going on strike.”

With a weak pro-company union, President Newell knew that he had the strikers over a barrel. Their most effective leverage was to strike, but they would face withering criticism that they were selfish, unpatriotic and un-American. Independent Brotherhood officials preferred that the workers stay at their machines and let the leaders take grievances before the National War Labor Board, a 12-member arbitration board of businessman and labor representatives established to mediate labor disputes during the war. The War Labor Board essentially replaced collective bargaining during the war because it could intervene in any labor disputes that it saw as endangering "the effective prosecution of the war" and impose a settlement.

Then in the early morning hours of Saturday, September, 30, 1944, 2000 shipbuilders, nearly every worker on the day shift, walked off the job in protest over BIW's delay in implementing an incentive bonus plan for hourly workers. By noon, 95 percent of the workers were out on strike. The Regional War Labor Board immediately called for the Independent Brotherhood to end the strike in compliance with the no-strike agreement because it interfered with "vital materials needed by our armed forces.” Independent leaders quickly met with the strike leaders in the "emergency committee" to hammer out a compromise.

Harold H. Chadburn, President of the Independent Brotherhood, acknowledged that there was “gross inequality in the take-home pay of employees.”

“We will do all in our power to bring the true facts before the management and process them through agencies according to government law," he told the press. "A referendum seems to be the best to determine the wishes of the majority."

As part of the t "return-to-work" agreement, the company agreed to send different options for the new bonus incentive plan to the workers for a referendum. The referendum asked whether the workers desired to continue the present individual departmental contracts; change to an overall blanket contract affecting all employees on an equal basis; or whether they wished to accept the management's bonus covering hulls completed since last July 8 and payable Nov. 29.

The workers also faced intense pressure from the government as State Selective Service Director Harold M. Hayes immediately requested the names, addresses and other information of all male employees ages 18 to 37 who did not return to work the following Monday. By leaving their jobs and striking, the men were now eligible to be drafted into the war. By Monday, the strikers were back at work and the plant was once again running at full capacity.

On October 10, the shipbuilders turned down a recommendation from the War Labor Board and voted in favor of an an incentive pay plan that would include all of them equally, so that every worker would share in savings on each ship delivered by the yard. One of the main complaints of the Bath workers during the work stoppage was that some employees were receiving incentive pay bonuses, while workers in other departments were still waiting for incentive pay in their department. The vote, at least temporarily, resolved a lot of the frustration in the yard over the company bonus pay system, though electricians were reportedly unhappy with the deal and briefly threatened another walk out.

It's possible that the company and the union could have prevented a lot of the unrest had it engaged with the rank and file workers and negotiated the compromise in the beginning, but in typical fashion, the Lewiston Sun Journal put the blame solely on the strikers.

“Until this strike, employees at the Bath Iron Works had been turning out destroyers with a minimum delay from labor troubles,” the editorial grumbled. “It is to be hoped they will return to that policy and will not again bring construction of destroyers to a stand still. The lives of too many American fighting men depend on those Bath destroyers to warrant any strike here.”

As the Allied Forces closed in on Germany in the spring of 1945, more unrest would bubble up on the home front in the little shipyard in Bath, Maine.

Tune in next week for “The CIO Strikes Back!”

Read the rest of the "Local S6 & the Spirt of the CIO" installments here:

PART 1: https://maineaflcio.org/news/90-years-later-local-s6-spirit-cio

PART 2: https://maineaflcio.org/news/90-years-later-local-s6-spirit-cio-0

PART 3: https://maineaflcio.org/news/local-s6-spirit-cio-when-biw-welders-launched-wildcat-strike

PART 4: https://maineaflcio.org/news/local-s6-spirit-cio-hicks-beat-city-slickers