Local S6 & the Spirit of the CIO: When BIW Welders Launched a Wildcat Strike

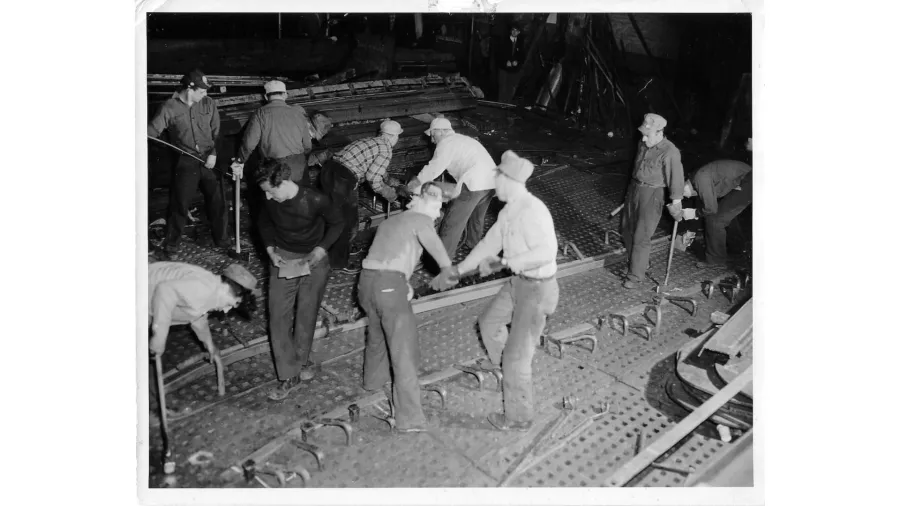

PHOTO: BIW shipyard workers sweat as they shape steel beams with sledge hammers for a Liberty Ship at the South Portland Shipyard. May 15, 1944. Maine Maritime Museum.

This is the third part in our series about the founding of Local S6, one of Maine’s powerful unions, at Bath Iron Works. You can find part one here and part two here.

On December 21, 1938, shipbuilders at Bath Iron Works lost their first union election to be represented by the Industrial Union of Marine and Shipbuilding Workers of America (IUMSWA), CIO. But while they were down, the pro-union workers weren’t ready to throw in the towel any time soon.

The welders were also the most pro-union shipbuilders because they knew that taking collective action was the only way to force the company to improve workforce safety. As welder and former union leader Arthur Lebel told an interviewer in 1972, the welders’ job was particularly hazardous because they had to work in poorly ventilated areas like the insides of tanks where they were exposed to zinc oxide and other poisonous fumes

“We were more militant than the other groups,” said Arthur Lebel. “The fact of the matter is in a few years after that, the welders organized themselves to a point where they wanted to do something about the conditions. They had no blower systems that take away the fumes from the welding arc and, when we worked in the bottoms of the ship there was no ventilation.”

The following spring of 1939, Bath Iron Works employed a record 2,400 workers at the yard as they worked to complete five Navy destroyers. In addition, the company had two additional bids in the process, but it was also facing the threat of a wildcat strike.

The welders had drawn up a series of demands for BIW, including the installation of a ventilation system, removal of clocks from welding machines and the establishment of a wage scale and classification system to address rampant favoritism at the yard. Although they didn’t officially have a union at the time, welders set up a meeting with BIW executives to present their proposals.

“I think we negotiated for five weeks and they agreed that our cause was just, that we should have more money, and that we should have better conditions, but they never gave in on a single item,” Lebel recalled. “ I think then that the welders got together and they decided to give the company a twenty-four hour notice that if we didn't get a realistic answer to our proposals that we would call a cessation of work.”

The welders were infuriated when all they received back from the company was a written statement on a plain piece of paper that didn’t even acknowledge their grievances. To preserve their "dignity and self-respect," the welders and tackers laid down their tools in a near unanimous action. The "dirty dozen” who scabbed during the strike were sent out to "mix" with the strikers with "more vague company promises" to try to get the men back to work.

PHOTO: The Peoples’ Baptist Church in Bath where the strikers at BIW held their meeting in the spring of 1939.

A federal mediator was eventually brought in to meet with both sides. Finally, the company agreed to some of the workers’ demands. The strike lasted for two and a half weeks.

“A federal mediator was sent in [and] we was able to re-classify not only the welders but the entire yard,” said Lebel. “And I recall at the time that the raises averaged from two cents an hour to thirty-six cents an hour. I think a man named Sidney Bean got a thirty-six cent an hour raise and they installed a fifty thousand dollar ventilating system, which I dare say has saved hundred of lives since that installation.”

As a result of the strike, the company also finally agreed to scrap its arbitrary piece work system for paying welders and established rates per foot. The company also agreed to give the workers lockers to store their gear instead of having them keep it in the blacksmith shop as they had prior to the strike.

“They put their arms around our neck and said, ‘well, you've done a good job and from now on if anything is wrong come and talk to us about it,’” Lebel added.

However, as Maine labor historian Charlie Scontras noted, the welders failed to win time and half for Saturdays despite the fact it was the practice at other shipyards. The workers’ pro-union newspaper The Shipyard Worker wrote that the yard “reeks of favoritism" because workers still didn’t have seniority rights. The company also found loopholes to avoid living up to its promises. BIW fattened its bottom line by demoting workers from a mechanics rating to that of a lower-paid handyman or helper.

The Shipyard Worker argued that the company and “its humble and obedient” The Bath Times newspaper continued to spread rumors of layoffs to intimidate workers and cultivate a “slave psychology” among the men. As the war raged in Europe, BIW’s profits soared thanks to war time contracts and industry-low wages paid to shipbuilders. As the Shipyard Worker asked its readers in April, 1940:

Why then should not the workers who build the ships share in this prosperity?

Why should the B.I.W. be one of the few yards to refuse to grant a wage increase in the last several months?

Why should the B.I.W. be the only yard without paid vacation?

Why should the B.IW. openly flaunt the seniority rights of its employees?

The answer was abundantly clear: “Organize.”

Stay tuned for next week’s installment of the Local S6 & The Spirit of the CIO!