90 Years Later: Local S6 & the Spirit of the CIO

PHOTO: lAMAW Local S6 member Doug Hall on strike on his birthday in 2020.

Whenever there’s a picket line in Maine, chances are you’ll see Machinists Local S6 member Doug Hall right there holding a sign. A stalwart union man since the 1980s, Hall was elected as a Local S6 shop steward in 1994 and elected to the grievance committee in 1998, where he has served for seven terms. He's also served as a chief steward and on the union’s negotiating committee during the 2020 strike.

Originally from Farmington, Hall said he didn’t grow up in a union household, but he developed a strong sense of class consciousness as a young man. After graduating high school in 1986, he went to work at the Forster toothpick factory in Strong where he and his cousin were members of United Paperworkers International Union Local 14.

Despite the town’s name, it wasn’t a particularly strong union, recalls Hall. But when thousands of Local 14 members walked off the job during the International Paper Strike of 1987 Hall became more radicalized. His uncle was among the strikers, so instead of scabbing like some of his former classmates, Hall joined his family on the picket line. A year later in 1988, he went to work at Bath Iron Works with a firm understanding of what it means to have solidarity for one’s union brothers and sisters.

“I went from making toothpicks to war ships,” said Hall.

It was there that he became a part of a long, militant union tradition going back to the 1930s when shipbuilders with the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) began organizing for better wages and workplace safety. With so many younger members coming to work at the shipyard in the past few years, Hall is passionate about teaching them about their union’s proud history and instilling in them the spirit of CIO.

Formed in 1935, the CIO was originally called the Committee of Industrial Organizations that worked within the American Federation of Labor. Led by charismatic United Mine Workers leader John L. Lewis, It changed its name to the Congress of Industrial Organizations after it broke away from the AFL due to a fundamental disagreement on organizing strategy and became a separate federation of unions in 1938.

Unlike AFL unions, CIO affiliate unions organized all workers — Black, white, men, women, skilled and so-called “unskilled” — into factory wide “wall-to-wall unions.” AFL unions only organized the highest paid skilled craft workers and typically excluded women and Black workers. The International Brotherhood of Boilermakers, then the largest shipbuilding union, refused to admit Black workers and instead placed them in “auxiliary” unions that put them in a “subservient position compared to the white unions.” Thanks to CIO organizing Black union membership grew from 100,000 to half a million from 1935 to 1940.

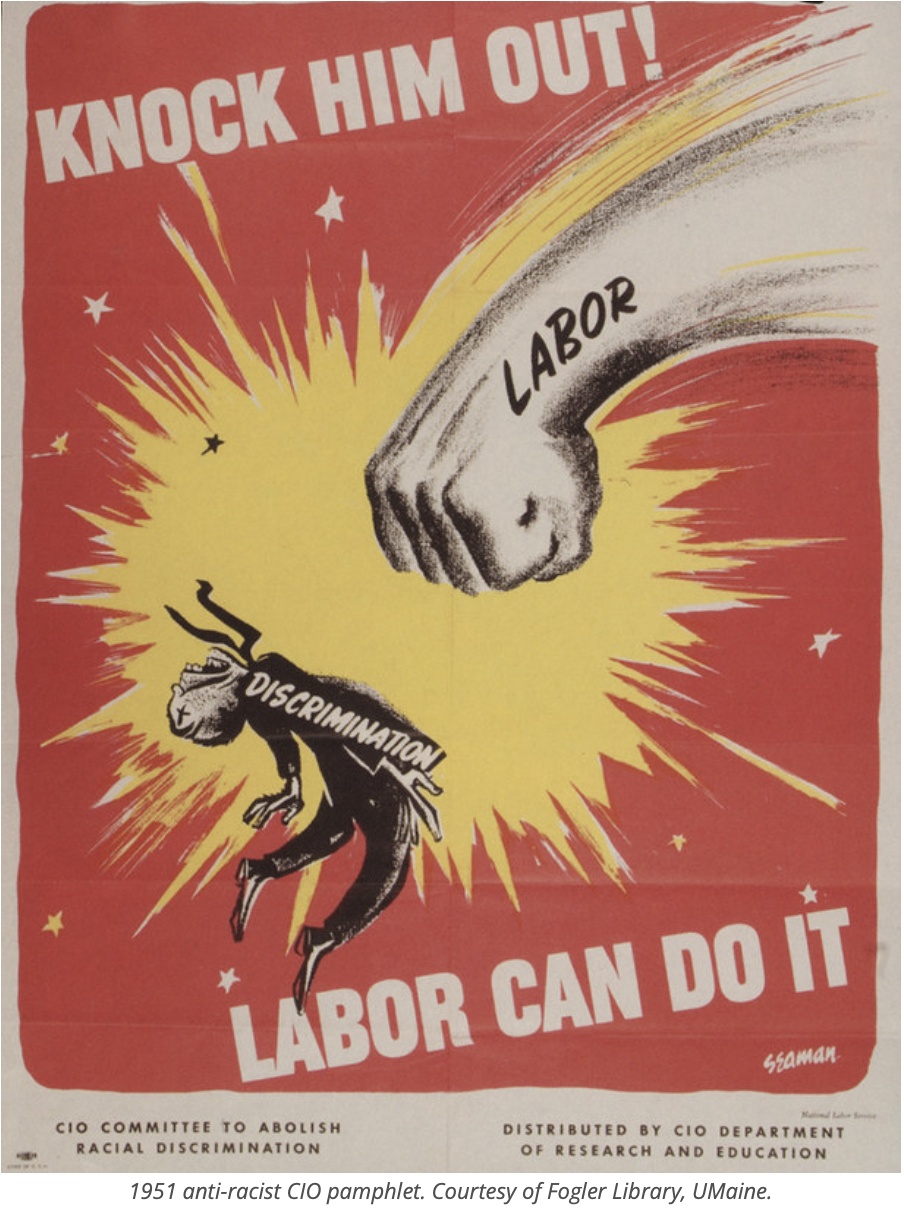

“The CIO’s philosophy was always ‘we’re all equal, it doesn’t matter.’ We were on the cutting edge of fighting racism during the CIO days of the 1930s and 40s,” said Hall. “I think it’s something we need to get back to teaching members. Human rights should always tie into being in a union.”

CIO supporters argued that while the craft union model may work in other workplaces, dividing workers in a single factory into several different crafts with their own agendas weakened workers’ collective bargaining power and left the lowest paid workers without union representation.

“As far as shipbuilding, we are the last industrial CIO union that represents wall-to-wall members. All of our production workers are organized under one umbrella, from maintenance and custodians to the skilled trades,” says Hall “Our philosophy was to organize the entire workplace because that’s the only way to beat the company. When we’re all in it together we have more power.”

Other shipyards have what are known as Metal Trades Councils, made up of several separate craft unions, but Local S6 includes all of the production workers. Hall argues that Local 6’s industrial union model makes it more militant because the company is less able to pit unions against each other.

“The company tries to drive wedges between workers wherever they can,” says Hall. “If they can divide workers by giving out raises to some and not others, or treating trades differently they will. Under the CIO model, it’s harder for them to do that."

The cornerstone to the Local S6 contract is seniority. Rather than simply laying off workers when work is slow in a particular department, there’s a provision in the contract that allows them to be loaned to other trades or take recalls into other departments based on seniority.

“That’s a lot harder when you get into metal trades council because they’re two separate entities,” Hall said. “If I’m a tin knocker in the sheetmetal union my primary concern are tin knockers because you’re elected by those people. Industrial unions are more radical.”

When Bath shipbuilders began organizing with the CIO in the 1930s, CIO workers were in the midst of massive nationwide struggles that culminated in collective bargaining agreements at US Steel and General Motors, following a dramatic forty four-day sit-down strike. From Detroit and Pittsburgh to the tiny village of Bath, Maine, the momentum was unstoppable.

For the 90th anniversary of the first union founded at Bath Iron Works, next week we will continue with the second part of “Local S6 & the Spirit of the CIO.”