When Portland Firefighters Formed the First IAFF Local in the State

PHOTO: Portland Fire Department's Engine 1. Portland Maine History 1786 to Present

It was a bright, freezing cold morning following a raucous night of New Year’s festivities in Portland’s Old Port on January 1, 1913. The streets were nearly deserted as a frigid easterly wind whipped between the downtown buildings. Suddenly, there was a crash in the cellar of the H.H. Hay Sons drug store at Middle and Free Streets that would cause the tragic deaths of some of the city’s most well-liked and respected citizens.

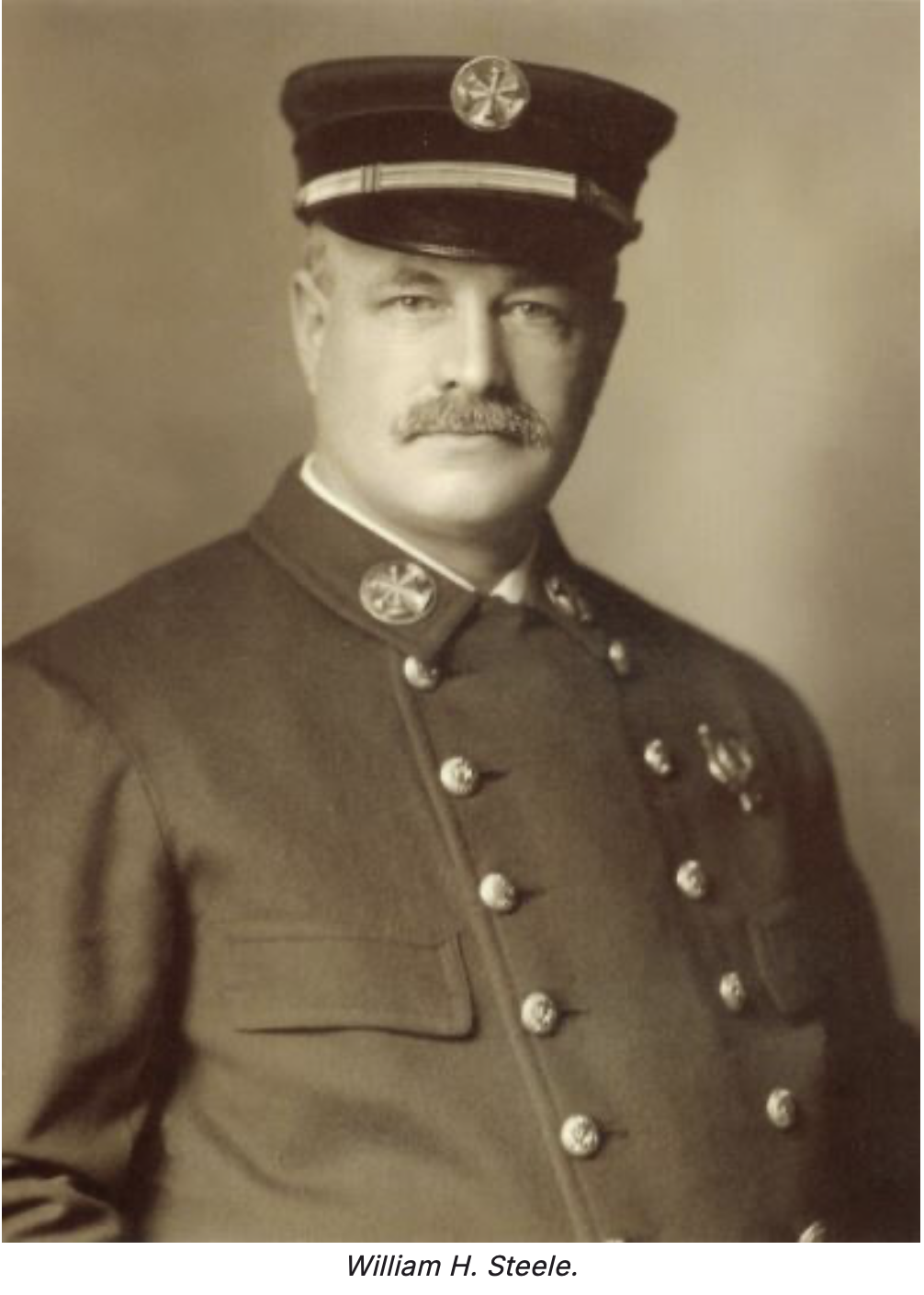

A store worker had accidentally knocked over a carboy of highly corrosive nitric acid, smashing it to pieces. As the deadly fumes filled the basement, the worker fled into the street to pull the fire alarm. The alarm rang in the firehouse at 8:45 am. Portland firefighters sprang from their places and headed out to see what the emergency was about. Normally, Fire Chief Patrick H. Flaherty would be leading the men toward the emergency. But he was out, so Deputy Chief William H. Steele was dispatched to the scene with Chemical No. 1. By the time the company arrived, the deadly fumes had filled the building.

A Proud, Storied History of Firefighting in Portland

Steele was well-liked by both the rank-and-file men and his superiors. He had a pleasant, genial disposition and got along well with everybody. He was also known as a courageous firefighter who didn’t shrink from danger. Steele was very proud to be a Portland Firefighter in a department that traced its roots back to March 29, 1768, when the city of Falmouth established “Fire Wards.” These fire wardens had police powers to direct firefighting efforts and order citizens to assist in fire suppression. As the population grew and fires increased, the Maine Legislature officially established the Portland Fire Department in 1831.

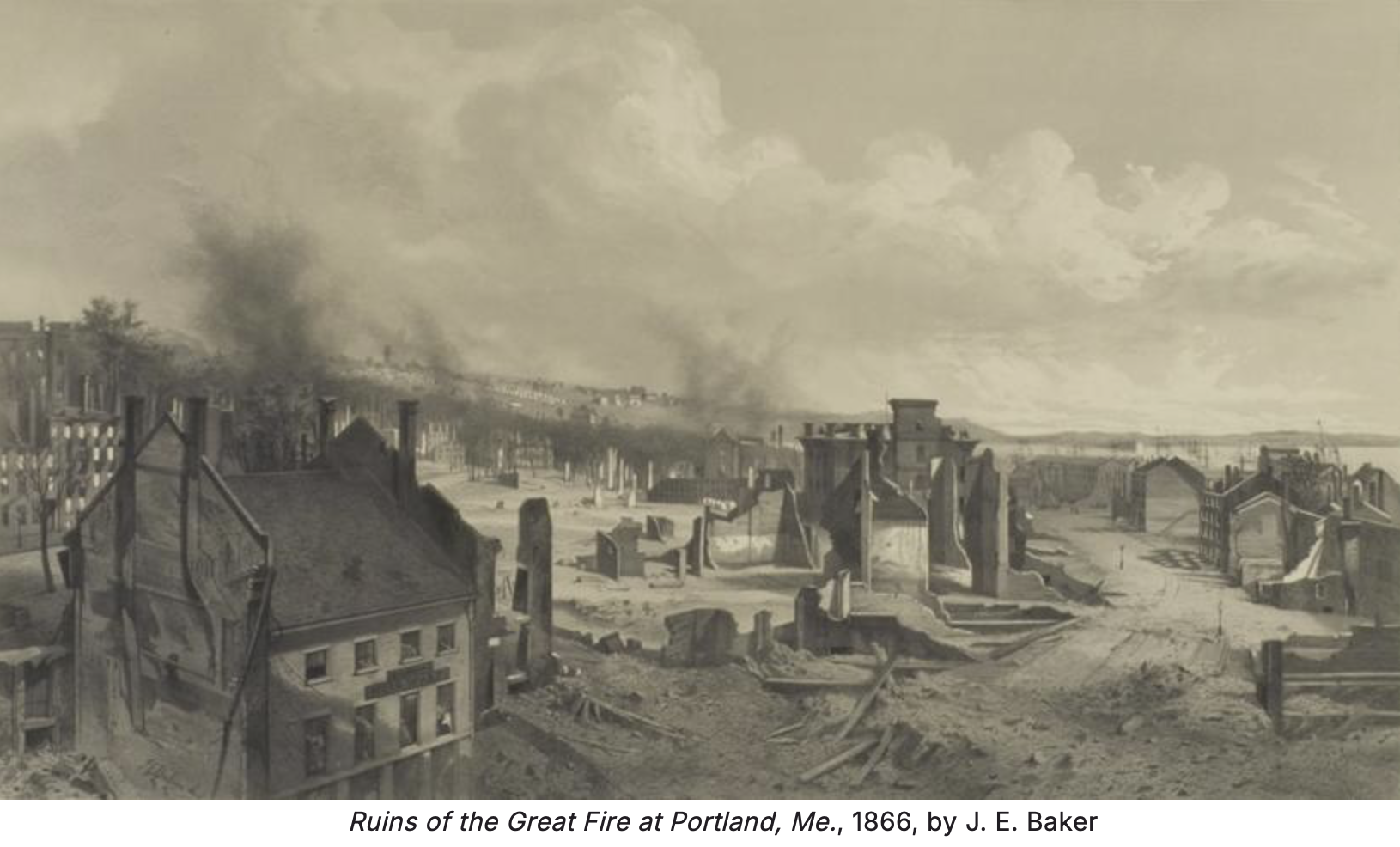

Steele liked to joke that he was there when the Great Fire of 1866 swept through downtown Portland destroying City Hall, the Customs House, the Post Office, all the city's banks, hotels, shops, offices and several churches.

“Oh, yes, I was in Portland all right during the big fire of 1866,” said then-Captain Steele, as he laughed in a 1909 interview with the Portland Evening Express, “but as I was only about three months old at the time, I will not attempt to spin any fairy tales based upon my recollections of it, for all I know about the big fire is what I’ve read and heard of it.”

But there were firefighters still working at the Portland Fire Department when Steele made those remarks. Captain Benjamin L. Sawyer, who was one of the first firemen on the scene that July 4, served on the department for 50 years, from the early 1860s to 1912. He always said he could not begin to explain what it was like, having never seen such a raging inferno.

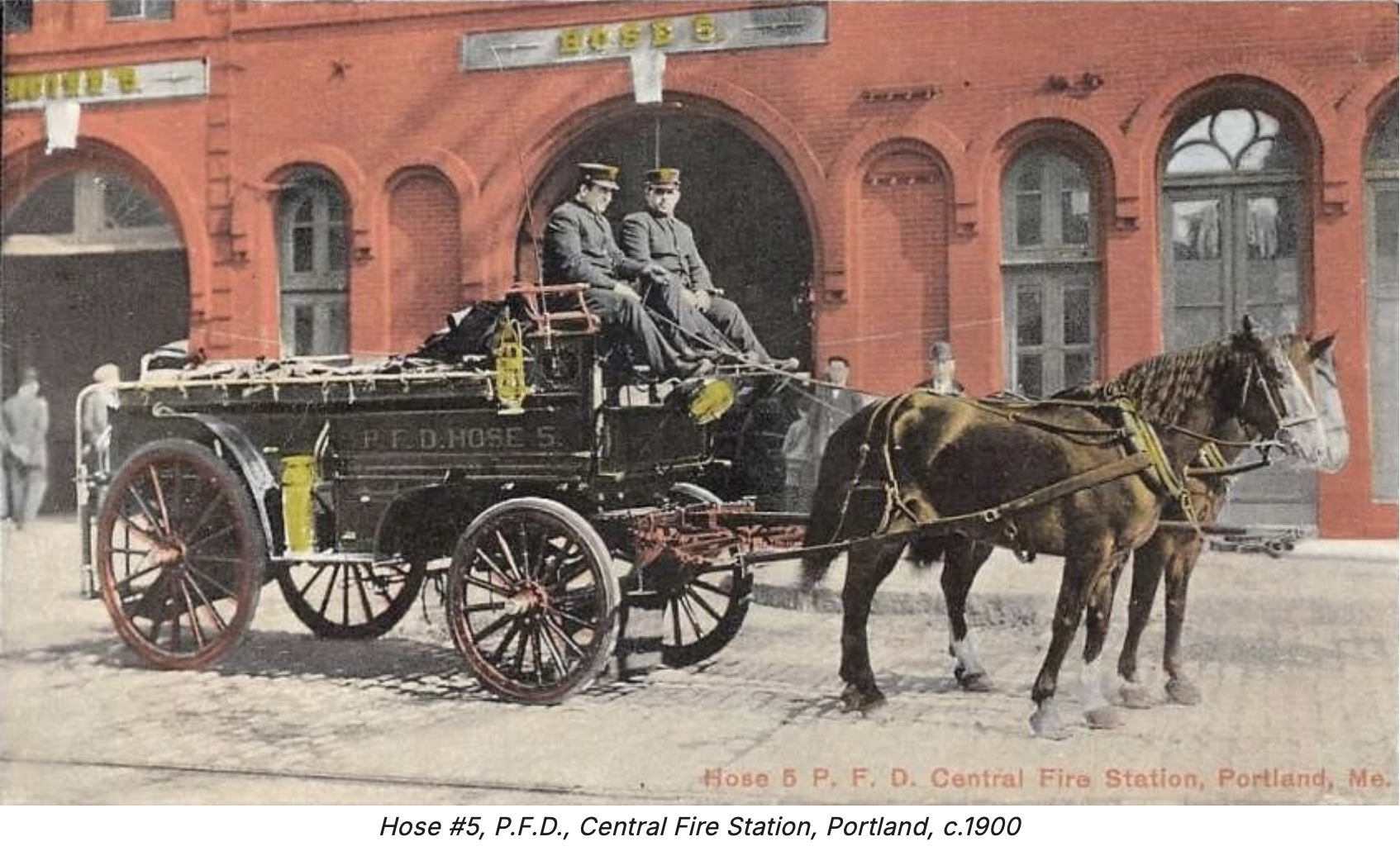

By the turn of the century. the Portland Fire Department became known throughout the Northeast for its skill at battling major fires. Firemen devoted their entire lives to the fire service in those days. There was only one shift so they basically lived in the fire house 24/7. They came home for meals, but had only one day off every eight days. There were massive fires that took out whole blocks. Steele was nearly killed at this first fire as a young recruit in 1894, when the largest mercantile establishment in the city went up in flames. The fire burned from 6pm until the next day.

“It was a bitterly cold night and the boys suffered from both heat and cold, for while they were facing the blaze, it was hot enough to suit anybody, but the moment they dropped back the icy temperature caused them to shiver and shake,” said Steele. “It was a case at this fire where a man’s face would be almost blistering with the heat, while his back would be freezing. I was assisting three or four members of 4’s company in handling a line in an alley way in the rear of the building, when without warning, a big section of the wall came down and for a few moments the hot bricks were flying all around us, although fortunately none of us were injured in the least”

A three-alarm fire at Brown's Wharf on Commercial Street in Portland on November 9, 1903. At left is Engine No. 1, an 1871 Amoskeag engine built as "Machigonne No. 1," the fire department's eighth steamer. At right is Engine No. 9 as reassigned, a Portland Company-built engine, formerly known as the "Cumberland No. 3," built in 1870. Courtesy of Maine Historical Society.

1908 turned out to be the most disastrous year for fires of the early 20th century in Portland. That year, fires consumed Portland City Hall, including the third floor Fire Alarm Office. The department purchased four steam engines for Engines 1, 4, and 9. Steele manned the horseless, steam-powered Engine 5 and Chemical 1 that year. He said that chemical company members “stand more punishment in a year than any other men in a fire department” because in order to aim the chemical stream effectively they had to be up close to the blaze, exposed to extreme heat and "eating" all kinds of smoke. It was “one blaze after another” that year, said Steele. He and his men battled fires in 70 mile-per hour winds that blew blazing boards, shingles and embers across the city for almost a mile. In 1911, Portland High School was destroyed in a fire blamed on bad electrical wiring.

In those years, the Portland Firefighters had to bury a number of brothers. They died horrific deaths in chemical explosions and roof collapses. They fell from ladders and died of asphyxiation from inhaling smoke and toxic fumes without protection. Others died too young of work-related PTSD and heart disease, but were never counted among the fallen.

The deadly Sturdivant's Wharf fire on April 25, 1903, took three firemen’s lives. Engine Company 2 hoseman Thomas W Burnham, 68, got trapped in the middle of the blaze and died two days later from severe burns surrounded by his wife and two sons in the hospital. Burnham, a native of Lubec, was a call man and temperance activist who made his living as a cabinet maker.

A month later, on May 22, Engine 3 Hoseman Clarence A. Johnson died at the Maine Eye and Ear Infirmary from severe burns he sustained in the same fire. His mother and his wife were at his side. A native of Limington, he was also a call man whose full-time occupation was brick mason. He left behind a daughter.

Hoseman Charles W Barrett, 41, was electrocuted by a high voltage wire at the Congress Square Hotel on Oct. 2, 1908. He was a Permanent member of the Fire Department, who had recently given his resignation. He planned to return to his previous occupation as a metal worker, so he could be home more to take care for his sick and invalid wife and their six children, all Under 11 years of age. Little did Chief Steele when he responded to the H.H. Hay Sons emergency that fateful New Years Day, he too would become another statistic.

A Tragedy at H.H. Hay Sons

When the firefighters arrived on the scene, Steele ignored the warnings of store employees and dashed into the fume-filled cellar followed by Lt. Ralph E. Eldridge of Chemical Co. 1 and the other men. As the Portland Evening Express reported, their only thought was to “eliminate the danger." But as soon as they reached the cellar they began choking on the deadly fumes. They bolted back up to the street for air.

“Revived, they rush back into the cellar, armed now with water-saturated sponges,” the Evening Express reported. “Again and again, they are driven to the street, choking, spitting and gasping for breath. Finally, the fumes subside. The acid is washed away.”

The firemen no sooner returned to their stations than another alarm rang, alerting them to a fire on the Number 2 Plant of the hardware and tire manufacturer E.T. Burrowes. Unaware that they were “sick unto death,” Steele and Eldridge rushed off to the Burrowes fire. They finally extinguished it at about 1pm and the men returned to their stations. It was then that the “insidious work of the poisonous nitric acid fumes” began to “bear its ugly fruit” and the men fell ill.

First Capt. William G. Parker of Ladder 5 became sickened, followed by John J. Gubbins, Chemical 1, and call man Silas H. Redmond Jr., Engine 4; and finally, Deputy Chief Steele. As the men were sent home, District Chief William R. Read was called in to take charge of the department. Steele died at 9’clock that night, leaving behind his wife Margaret and two adult sons. Lt. Ralph H. Eldridge passed away at 4am the next morning. Steele was 46 and Eldridge was 34.

On January 4, 1913, a massive crowd of firefighters and mourners gathered at the First Baptist Church on Congress Street to pay their respects to the fallen deputy chief. From 12 to 1, Steele's body lay under guard by members from the department and hundreds who were unable to attend the services viewed his remains. Department members assembled at the Central Fire Station and marched to the church, the casket placed nearly hidden by large banks of flowers.

After the service, the apparatus at the Central Station was driven by the church and the firemen stood at attention while the casket was placed in the hearse. The procession was headed by a platoon of police commanded by Sergeant Stephen H. Cady. Following the hearse was the chief’s team bearing the hat of the deceased deputy and Chandler’s First Regiment Bang played a funeral dirge. Eldridge’s funeral was held at Woodfords Congregational church. Hoseman Harry E Harmon of Engine Co. 6, 41,

Two months later, the Portland firefighters had bury another brother. On Tuesday, March 18, 1913, Hoseman Harry E Harmon died from pneumonia as a result of smoke inhalation from a two-alarm fire at the Royal Remedy Company on Commercial Street on March 7. The 41-year old call man was also a driver for the grain dealer WH. Thaxter Company. He left behind his wife Edith and three children, Amy, 14; Franklin, 17; and Harry, 15.

Four other firemen remained critically ill from inhaling the toxic fumes at the drug store. Capt. Parker was the sickest among them and died a year later. Capt. Black, a firefighter named Redmond, and John J. Gubbins, recovered after a few weeks. But the trauma of the incident and other deadly fires over the years would haunt Gubbins for the rest of his life. In 1918, he would join a group of other Portland firefighters to form the first firemen’s union in Maine with the newly established International Association of Firefighters.

For the next 25 years, they would organize and fight for a two-platoon system so that they would have time to spend with their families because they never knew if it would be last time they saw their loved ones the next time the fire alarm rang.