When Firefighters Went on Strike in Bath and Skowhegan

PHOTO: Downtown Fire of 1894, Front Street, Bath

At the beginning of the 20th century, municipal firefighters in Maine began to look around at other workers unionizing and realized that they too could improve their wages and working conditions through collective action. But before firefighters unionized, they took part in a number of strikes. In the first part of our series on the history of firefighters’ unions in Maine we covered the first recorded public employee strike in the state in 1862. This week we will look at two major firefighter strikes that occurred in Bath and Skowhegan in the early 1900s.

Firemen in those days were known as "fire laddies" and used both hand-pumped engines and newer horse-drawn apparatus to fight fires. The first firefighter strike of the 20th century fell on June 2, 1904, when the Bath Fire Department’s entire volunteer force of 55 men "threw down their badges and announced that they would not respond to fire alarms” after the City Council failed to grant a $60 increase in their stipend to $100 a year. According to news reports, their demand was submitted to the chief engineer who failed to notify the City Council. So when it took no action on their demands, the firemen walked out. The City Council members and Company C. of the Second Maine Regiment volunteered to temporarily fill in for the striking firemen.

“I have secured the services of a sufficient number of men who will man the different companies until tomorrow night when new companies will be organized to fill their place,” Chief Engineer Morse told the Bath Times.

First Lieutenant George A Buker of Company C. Later clarified that the company was only to act “in the capacity of citizens without uniform, not as a militia company and not to take the places of striking firemen.”

Two days later, the Bath Daily Times reported that the striking firemen were willing to resume work for a $10 raise to $50 a year. The strikers claimed that they had not been treated fairly by the City Council and that the Aldermen should have sent a committee to explain the matter. They said they asked their chief to contact the Aldermen but he failed to do so. Not surprisingly Maine’s predominantly conservative newspapers were highly critical of the firefighters. And unfortunately, there it offered few opportunities for the strikers themselves to speak out and defend themselves.

The Biddeford Saco Journal acknowledged that while firefighter pay was low, “membership is entirely voluntary, and to jeopardize the safety of the city by resigning in this manner is fairly good evidence that the men who resigned were getting all they were worth.”

The Lewiston Journal wrote, “No doubt the firemen deserve more pay, but Bath is still too heavily in debt and pays too high taxes to give more generous wages to its public servants,” the Journal wrote. It added that the city council members and the local militia would ensure the “fires will be attended to in a dignified, judicial and military manner.”

However, by July 17, the Bath Daily Times reported that the ongoing strike was creating a “dangerous situation” and city leaders weren’t doing anything to fix the situation.

“While an unpracticed and miscellaneous body of City Fathers, military men and citizens, all captains and no privates, is undoubtedly able to cope successfully with an ordinary fire, if it were suddenly to come face to face with a great one, inexperience and disorganization would prove a source of great peril to the city, and it is not improbable that in the event of a large fire loss under the existing circumstances the insurance companies might refuse to make the losses good,” the Times opined.

The editorial argued that if the fire chiefs were unable to organize a new force at the pay being offered, they should resign. A week later, Mayor John S. Hyde, son of Bath Iron Works founder Thomas Hyde, called a special joint meeting of the Council and Aldermen where Chief Engineer Morse was grilled over his failure to find scabs willing to work for $40 a year. The aldermen were split in their support for the striking firemen. One alderman complained that the strikers were “grasping the city by the throat” to get a wage increase. At the end of the meeting, the lower board (city council) voted 15-3 to increase the annual stipend to $50, which the strikers had asked for weeks earlier. But the Alderman voted 4-2 to reject the proposal. After both sides met in a committee of conference in a closed door session for 70 minutes, councilmen and aldermen finally agreed on a proposal to organize a new department with a 10 percent wage increase.

On August 29, firemen anxiously waited outside City Hall for the Alderman to release the new department rolls. Although the chief engineer recommended that the strikers be rehired, in the end city officials opted to permanently replace them.

The Skowhegan Firemen’s Strike

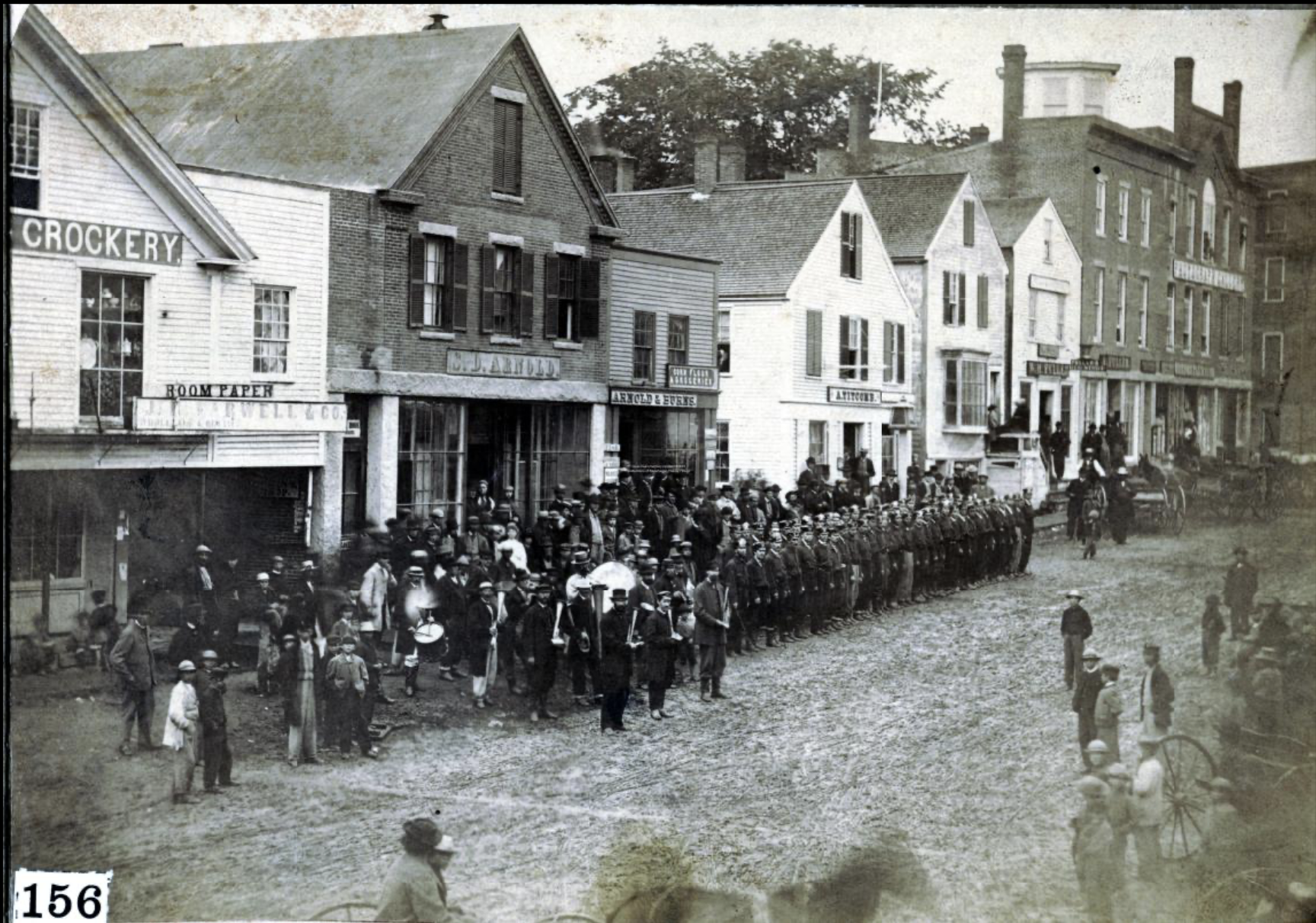

PHOTO: Westerly side of Madison Avenue, Skowhegan, ca. 1870. Skowhegan History House

Five years later, in July of 1909, 45 members of the Skowhegan Fire Department went on strike over a wage dispute. As the Bangor Daily News reported, the firemen asked for more pay and were rebuffed by city leaders who did “not see fit to pay a price to men to fight the fires.”

According to the BDN, after a major fire burned down much of Milburn Black on Water Street, the town voted to appoint a fire commission of three men - A.K. Butler, George Webb and Clyde Smith, husband of future Senator Margaret Chase Smith - to reorganize the fire company. They hired an “experienced fire fighter from Bangor” to train the men. It also hired Anson Savage as the chief of the company, who would live full time in the fire house on a salary of $750 a year. Two assistants were hired for him at a salary of $50 each. The department consisted of three companies of fifteen men in each. The men were paid a salary of $36 per year. The rank-and-file firemen demanded an additional forty cents per hour after the first two hours of firefighting.

The BDN noted that Skowhegan had experienced some of the worst fires in New England and had lost several of its “best business blocks” to fires over the past ten years. Fires had consumed Heselton block, a large hotel (twice!), Coburn Hall and blocks across Madison Avenue and Walter Street. Then in December, 1908 blaze wiped out five homes and “two of the finest brick blocks in the town.”

“It was not strange after this catastrophe that the citizens began to think that the fire company should be reorganized, but like the fellow who was going to build a house had no money to build with, and so Skowhegan has made good resolutions but no money with which to carry them out,” the BDN wrote.

It's not clear how the strike was resolved, but the fire company was back in action by the following October.