Saco Firefighters Launch the First “Public Employee” Strike in Maine

PHOTO: Saco Fire Department, 1870. Dyer Library/Saco

On May 1, 1862, volunteer firefighters in Saco launched what would become known as the first public employee strike in Maine. While the firemen were “technically” volunteers and not public servants, “in practical terms,” wrote the late labor historian Charlie Scontras, “the line would seem to be rather blurry as far as citizens were concerned.” The community relied on these volunteer fire companies, he wrote, to protect lives and property while the companies gave members a sense of a sense of public duty, social status and comradeship.

They were also a “colorful” bunch of men, whose fierce ambition often led to pitched battles with rival companies in the days before firefighting was more professionalized. Whiskey-fueled fist fights for possession of fire hydrants and acts of sabotage, such as cutting a rival’s hose, were common. Occasionally volunteers “paused from their heroic labors” to “pocket valuables salvaged from the burning buildings,” according to to Scontras. Likethis memorable scenefrom the film Gangs of New York.

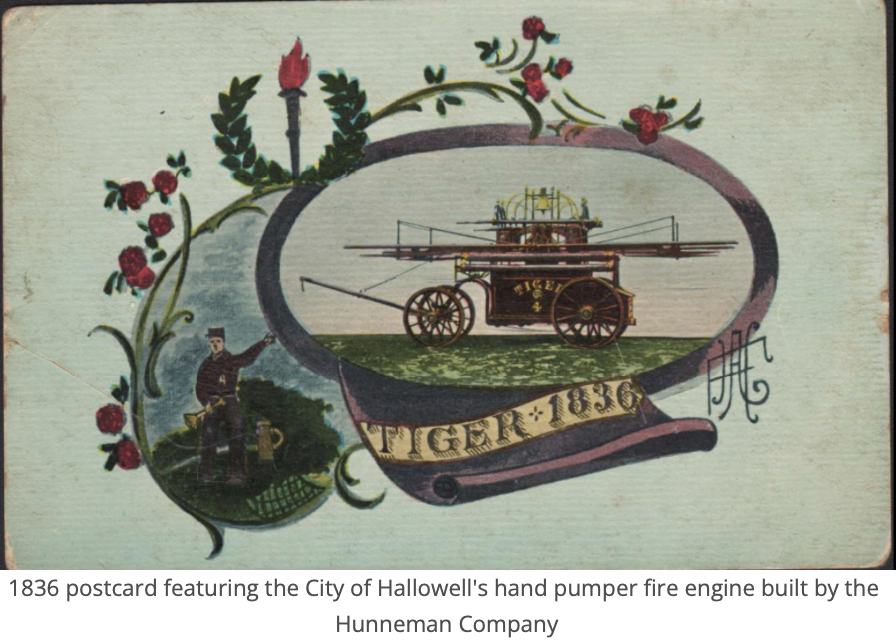

Saco had some form of fire fighting capacity since colonial days, but its first organized fire department was established in 1834 with the formation of the Saco Mutual Fire Club. The town purchased its first Fire Hand Engine called the “Niagara” in 1848, followed by a second one called “Deluge” in 1854. the fire department formed two companies, the 85-member Niagara Company 3 and the 60-member Deluge Company 4. In 1862, the economy was booming as Maine’s factories ramped up for wartime production, but Saco was not doing well economically and it was expected that there would be efforts to reduce spending at the town meeting. Since 1851, the Saco Firefighters had been receiving some compensation for their service, but when it came time for a raise in 1862, rural residents of the community mobilized to vote it down.

Firefighter and local jeweler Charles Twambley, the Chairman of the Board of Fire Wardens, explained in a letter to the Saco-based Maine Democrat that the the fire companies had presented a proposal to provide $800 for the fire department to increase the firemen’s pay. A committee was then appointed to discuss the matter and ended up recommending just $650 without consulting the fire companies. The move “touched” the firemen’s “dignity,” wrote Twambley, and their hurt was compounded by the meeting’s rejection of their proposal to build a new brick Hook & Ladder house to replace one that burned down. What followed, according to the local press was “the irrepressible conflict between the firemen and the citizens.”

On March 26, 1862, the Saco fire companies held a joint meeting where the firefighters unanimously adopted a resolution expressing their displeasure with the vote on their compensation. They pledged to walk off the job on May 1st if their demands were not met. The resolution stated:

Resolved, That we, the members of the Fire Department of Saco, in joint convention assembled, taking into consideration the late action of the town in regard to compensation of our Department, desire to express to the inhabitants of the same that we do not deem it expedient to continue our services under existing circumstances, and therefore do instruct our officers to deliver up to the proper authorities of said town the engines and apparatus, and any other property of theirs now in our possession on the first day of May, A.D. 1862.

The firemen provided several weeks advance warning so that the town could organize new fire companies to ensure that it would not be “at the mercy of a gang of hoodlums or firebugs.” Twambley recommended that the Selectmen appoint Fire Wardens to a committee and “see if some satisfactory arrangement" could be made for both sides. ”

In response to the announcement of a strike, the Saco Selectmen — David Fernald, Henry Simpson and Henry J. Rice — agreed to assemble a committee of fire wardens, who acted as public employees to oversee the department, in an effort to avoid the dissolution of the fire companies. The community was deeply divided over the looming strike, with some supporting the firemen and others calling it a “holdup." Some urged the town to “call” their “bluff” and form a new fire department to replace them. In a letter to the Maine Democrat, the foremen of Niagara 3, Deluge 4 and Hook and Ladder 1 called the criticism "the offspring of minds more fertile of evil than of good.”

“It is indeed to be regretted that so efficient a Fire Department as that now existing in this town should be broken up, unless it is morally certain, one equally as good can be re-formed upon its ruins,” the men wrote. “Many of us have been connected with this department for the last 12 years, and have labored assiduously to bring it to its present state of efficiency, and we cannot now look upon its dissolution without many regrets.”

The letter was signed by wardens Owen B. Chadbourn, a temperance activist and carriage and sleigh maker; H.D. Hanson, and attorney Rufus P. Tapley, who would go on to become a justice at the Maine Supreme Judicial Court. During negotiations, the firemen stuck to their promise to remain on the job and put out a fire that swept through a two tenement building in the city. The Democrat praised the firefighters for doing “good service on this occasion in checking the fire, or much greater damage would have resulted.”'

At the April 3 meeting of the fire wardens, it was agreed that an additional appropriation of $250 as part of a $1000 budget for all three fire companies. They put forward that recommendation to the selectmen along with $1200 to build a new hook and ladder house to replace one that had burned down. Eventually, a deal was struck between the Selectmen and Fire Wardens to forego the building of hook and ladder house for another year in favor of the $1000 budget to increase the firefighter compensation. However, rural opponents of the wage increases petitioned for another town meeting on May 3 to undo the compromise. Twambley condemned the decision to hold another meeting, arguing that the “Firemen have shown their magnanimity and a disposition to compromise”

“Now as far as my knowledge extends the Firemen have acted in good faith towards the town,” Twambley wrote. “They are composed of our best citizens — men of property and integrity — and they ask for nothing more than justice. Although they are willing to serve the town both by day and by night in the capacity of Firemen, they don’t consider that this act of humanity disfranchises them in the least from their rights as Citizens.”

After the opponents managed to blow up the compromise at the May 3 town meeting, a frustrated Twambley threw up his hands and announced his resignation. In a follow-up letter on May 5, he wrote that the outcome of the vote “forbids that any member of the old organization with a just sense of self respect should longer remain in service” and that they must withdraw from the fire service. He complained that village residents were not able to address matters that were important to them like the Fire Department without interference from people outside the village. He said, many of the firemen didn’t even vote at the town meeting because they were so “disgusted with the proceedings.”

“By their vote on Saturday last they have decided that they, (the people) know better about what is for the interest of the town than I do myself, or any of my associates in the board of Engineers,” Twambley wrote. He added that as his services “do not appear to be appreciated by the town, and they have chosen to take measures against our convictions of justice."

He concluded his letter by stating those who were “instrumental in destroying the old” fire department should now be responsible for forming a new one of equal efficiency and effectiveness in protecting the Biddeford-Saco community. On May 8, two new groups of firemen reformed the Niagara and Deluge companies.

The day after the new companies were formed, a fire alarm went off at midnight. Daniel Campbell, who resided on Middle Street in Saco, had caught sight of a bright light in front of his house. He discovered three men setting fire to a stack of hay in cart, which they rolled towards the fence. Soon flames were shooting up near the top of the house. Campbell and some of his neighbors pursued the arsonists, managing to tackle one of them, a Mr. Wentworth, who was promptly taken to jail. On the following Sunday, the police arrested the other two accomplices, Stephen Milliken and John Littlefield. Wentworth was admitted as State’s evidence, and the other two were fined $6 and costs, $10.80 each.

Milliken paid his fine and costs, and Littlefield was sentenced to jail time. A small vacant house on Birch Street in Biddeford was also believed to have been set on fire by arsonists that night. The Democrat suspected that “these fires were set with the design of calling out the newly organized fire departments.” The strikers, according to a local citizen, greeted their replacements "with hootings and abusive language.” In a letter to the Democrat dated May 13, a resident with the pseudonym “Citizen” praised the performance of the replacement firefighters and said it proved the old fire companies wrong that the community would not be properly protected if they were replaced. Citizen argued that the behavior of some of striking firemen alienated residents:

Up to that night (Friday) the writer of this had taken but little interest in the content between the town and the old fire department, but the insulting yells of many members of that organization on that night, the abusive and vulgar epithets applied by them, to many of our best and most respectable citizens, and the apparent pleasure with which some of their number, who claim to have some sense of propriety, heard the course mockery of their comrades, furnished abundant evidence that the town has got rid of that department none too soon. They may preserve their organization and as they threaten they will do, endeavor to control the affairs of the town, but unless they improve their manners and apparent dispositions, no respectable man will, for a great length of time give them support.

Although the old fire companies lost the strike, the striking firemen then reorganized a new fire department called the the "Ex-Fire Association of Saco.” Despite his resignation announcement, Charles Twambley would continue on as Chief Engineer and many of the firemen would go on to assist the Portland Fire Department in battle the Great Fire of 1866.