As Private Investors Seek to Buy Up the Land Beneath Her Home, MSEA Retiree Recalls Growing Up in Union Co-op Housing

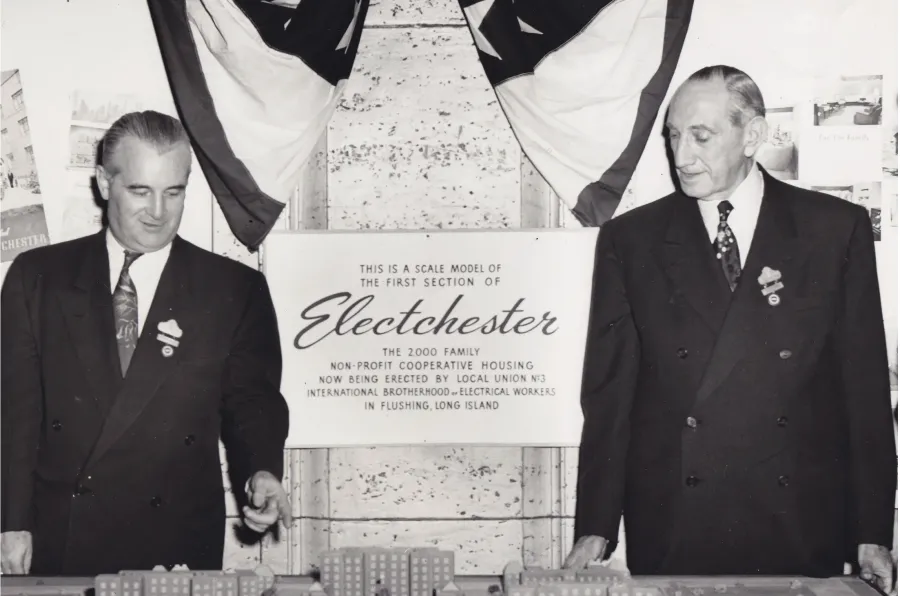

PHOTO: Harry Van Arsdale unveils a model of Electchester. Photo: Archives of the Joint Industry Board of Electrical Industry.

Last spring, a group of residents from the Friendly Village manufactured home park in Gorham got together to address a looming threat to the future of their community. For the past 43 years the land has been owned by Maine Mobile Homes LTD, but they had recently received a letter in their mailboxes from an attorney stating, “The owners have decided to sell their holdings in all states as a portfolio which includes Friendly Village manufactured housing community in which you reside."

The Wyoming investment firm Crown Communities LLC planned to buy the 302-lot park as part of a package deal for $87.5 million. Throughout the nation investment firms have been buying up mobile home parks from small mom and pop operations and then jacking up rents and fees to get a lucrative return on their investments, often without making any meaningful improvements. As a result, the residents of these parks, many of them elderly and on fixed incomes, are left high and dry. They may own their homes, but not the land beneath them and it's often unfeasible and cost prohibitive to move their homes. A manufactured home park is typically the last option for affordable housing.

Under a new contract, Crown Communities would only have to keep the status quo for five years. After that, residents feared the firm could turn it into an expensive gated community as it had done elsewhere.

“I probably couldn't afford to pay any more because my husband is now in a nursing home and I pay almost $2,000 a month for that to the state,” said Kathleen Kadi, a retired state worker and member of the Maine Services Employees Association. “It's a shame for people here to lose it because a lot of them are older and on fixed incomes and would have nowhere to go. It's a more affordable place to move to as a working person too.”

Kadi pays $600 a month for the lot and has done several improvements on the property over the years, including putting in a new patio, having the porch redone and landscaping.

In April, the park residents decided to form a housing cooperative and 80 percent of them voted to move forward with making an offer to purchase the property themselves. In 2023, the Maine Legislature passed the “Opportunity to Purchase” law that gives residents of a mobile home park 60 days to put forward a matching bid on the property if an outside company offers to purchase it. The law requires the owner to negotiate in good faith. Since the law went into effect, three offers by residents of mobile home parks have been accepted while six were rejected.

Nora Gosselin of the Cooperative Development Institute, which helped put forward the offers, argued before the Maine Legislature in April that the law still wasn’t strong enough to give residents a fair chance to purchase the parks. As an example, she noted that residents of Old Orchard Village and Atlantic Village launched a “herculean organizing effort” last year to raise $40.405 million for an offer to match a $40.4 million offer from a then-anonymous third-party buyer.

“During negotiations, the resident cooperative agreed to increase their offer by an additional $100,000 and to shorten their timeline,” said Gosselin. "Still, this wasn’t sufficient; the seller rejected the co-op’s offer because they didn’t believe there was enough resident support or that the residents could secure financing. Neither of these concerns were founded.”

CDI and the Friendly Village residents advocated for passage of a new law, sponsored by Sen. Tim. Nangle (D-Cumberland), which will give a group of mobile home owners or a mobile home owners' association the right of first refusal to purchase their park if the owner intends to sell it. However, the bill did not receive the necessary two-thirds vote to pass as an emergency measure, so it won't help the residents of Friendly Village. The sale to Crown Communities is unfortunately likely to go through.

Growing Up in Union Cooperative Housing

The cooperative housing model is not a new one and unions once led efforts to develop these projects for members. Kathleen Kadi herself grew up in Electchester, a nonprofit cooperative housing complex of 38 buildings in Queens, New York. The project was constructed in 1949 by Local 3 of the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers, of which Kadi's father was a member. As a child, Kadi recalls moving around a lot, but once a slot opened up at Electchester in the 1950s, the family seized the opportunity and moved in.

The project was spearheaded by Local 3 Business Manager Harry Van Arsdale Jr., who later became President of the New York City Central Labor Council. Arsdale and the Joint Industry Board of the Electrical Industry purchased 103 acres on the spot of a former country club in East Queens for the project. By 1953, golfers were replaced by working class New Yorkers and their families. As New York Magazine reports, the down payments for the apartments began at $470, and the monthly carrying charges were a maximum of $28.27 per room, depending on room size and income. It noted that the apartments were extremely cheap until the co-op lost state-tax abatements in the 1990s, but the carrying charges remain under market with down payments ranging from $7,000 to $16,250.

The complex contains a shopping center, a public school, a library, a popular bowling alley, athletic fields, a basketball court, basement rumpus rooms for kids and space where a variety of clubs meet. It also still houses the Joint Industry Board of the Electrical Industry. Along the complex are two shopping centers, a public school and a library. Van Arsdale himself later lived at Electchester in one of the “Towers,” a fancier set of buildings with larger apartments and private terraces.

“It was a good place to grow up,” recalled Kadi. "There were always fun activities for kids."

Electchester had its own athletic association and Kadi’s father served as its President for a time. She fondly remembers playing on the softball team and watching a football game once a week. There was also a small gym for boxing and a neighborhood hockey team called the Jokers.

“We found girls wanted to be on the softball team, but the coaches and the boys said, ‘no way.’” Said Kadi. “So we had an all-girls team and the girls team won!””

At the end of the season each year, Electchester residents would have a big outing at Jones Beach in New York where the top teams would compete against each other. One year, both the Electchester boys and girls teams had won nearly every game so they were set to play against each other. The boys didn’t show up so the girls won by default. Kadi proudly remembers being part of that year’s championship team.

“And as a co-op, they improved the buildings and kept the grounds up as we got older,” said Kadi. “By the time my parents left, they put in air conditioning and things that we didn't have when I lived there as a kid."

As the labor writer Ari Paul writes, the movement for cooperative housing in the early 20th century was part of “a grand, radical labor plan to unite the working class.” Kadi’s grandparents lived in co-op housing developed by the International Ladies Garment Workers Union in the 1920s. Meatcutters, typographers and other unions also got into the game and by the early 1950s, there were nearly 40,000 units of co-op housing in New York City, writes Paul.

As Joshua Freeman, a professor of labor history at the CUNY Graduate Center and the author of Working-Class New York, told Paul in 2013, the Electchester co-op housing development was made possible thanks to federal funding from the 1949 Housing Act, which helped hire idled workers and purchase the building materials.

“The end result continued the spirit of the New Deal: public investment to hire workers, enable prosperity, and deliver a physical and utilitarian infrastructure for the long-term use of those we today would call the 99 percent,” wrote Paul.

He attributes the decline of union cooperatives to New York City’s financial crisis in the 1970s and the federal government’s decision over time to cut funding for subsidized housing. With about 6,000 residents, half of whom have family ties to Local 3, Electchester remains an example of the potential for unions to play a role in creating affordable housing. As former union president Charlie Fahlikman, a resident since 1954, told New York Magazine, he paid $139.10 for his two bedroom and now it's $1,250, well below the average price for a similar apartment in Queens.

“I met my wife in the building. One of my childhood friends was just back from Vietnam, and he came to see if I wanted to play tennis in Cunningham Park with his girlfriend, Pat, and her friend,” said Fahlikman. “I’ve been married to the friend for 50 years. For our anniversary, we went to Valentino’s on Kissena Boulevard. The owner there calls me “Mr. Electchester.”