Portsmouth Naval Shipyard Workers: More than 225 Years of Struggle for Dignity, Fair Wages & Workers’ Rights

Photo: The launch of the USS Washington at Portsmouth Naval Shipyard on October. 1, 1814,, with the USS Congress (1799) in attendence. Painting by John Samuel Blunt (1798-1835)

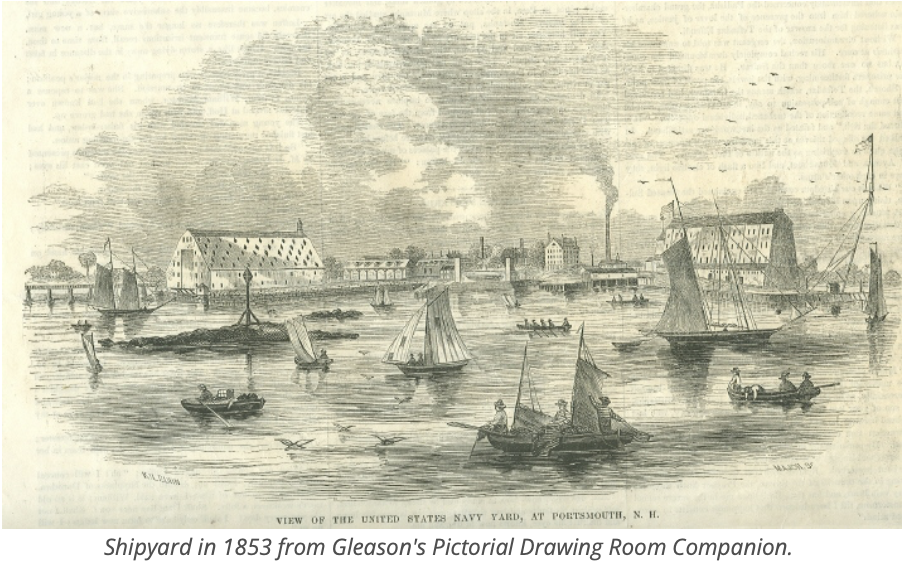

For the past 225 years, Maine and New Hampshire workers have built and maintained ships at Portsmouth Naval Shipyard, the second longest surviving Navy shipyard in the nation. For much of its existence, the beleaguered shipyard has faced threats of closure, but has somehow managed to weather the storm from the age of sail and steam to diesel and atomic energy. These days, the workers at the yard overhaul, repair, and modernize submarines.

The shipyard’s unionized workforce has overcome a lot of adversity over the past 100 years, from virtually no rights to collectively bargain over their working conditions, to finally winning that long fought struggle 60 years ago.

Now they face an unprecedented attack by President Donald Trump, who has stripped them of their collective bargaining rights in an attempt to deprive them of their right to exist. But unions existed at Portsmouth Naval Shipyard long before they were legally recognized and they will continue to fight for their rights. Some of them may even have ancestors who were there from the very beginning when workmen stood ready to defend the shipyard from the British Navy with their lives if necessary.

A History of Workers’ Struggles

The Kittery Navy Yard was established on June 17, 1800, during President John Adams’ administration. It was originally built on Fernald's Island, which is now conjoined with five other islands to form Seavey’s Island in Kittery bordering Portsmouth, NH. As historian Dennis Robinson writes, the US Navy determined that the rugged island at the mouth of Piscataqua River, which fishermen previously used to dry salted cod, was the best spot to build warships because it could be heavily fortified. But it also had its challenges, such as fog in the late summer months and a rapid current that made navigation only safe at high tide. The area was also attractive because it had access to raw materials like lumber from local forests and it was home to skilled craftsmen who had been building warships there for over a hundred years.

The fifty-gun ship HMS Falkland, which was commissioned there in 1696, was the first British warship built in the Thirteen Colonies. During the American Revolution in 1776, Piscataqua shipbuilders completed the Raleigh on Badger's Island in Kittery, though it was later captured and served in the British Navy. According to Mark Dennett of Kittery, a brother of the former owner of Fernald’s Island, the island was then covered with a dense undergrowth with a single elm tree, a small stream and a swamp extended to where a dry dock was later built. There was only a small two-story house his brother built and a fish shack there when the Navy began building the shipyard in 1800.

The first vessel built at the new Kittery Navy Yard was the 74-gun ship of the line USS Washington, which was completed in 1814 during the War of 1812 (it was broken up in 1843). As historian Walter Fentress writes is his book “1775-1875: Centennial History of the United States Navy Yard, at Portsmouth, N. H,” the port was closely blockaded by the British Navy and the workers lived in constant fear of an attack as they anxiously watched British vessels cruising back and forth between the mainland and the Isle of Shoals. Fearing that the British would do a night raid and burn up the USS Washington before it was even launched, the shipyard’s commander, Commodore Isaac Hull, convened naval officers and local militiamen to devise a plan to defend it should a raid occur.

Dennett told Fentress that the firing of three guns would be the signal to assemble the troops in the event of an attack.

“I was then about 29 years old, and an officer in a company of minute men at Kittery,” Dennett recalled. “One cold night the heavy report of three cannon came booming over the water, and in a few minutes, our men could be seen hurrying to the rendezvous in numbers. When I arrived, I found about sixty assembled and we took up our line of march to the Yard by way of Kittery. One old gentleman, who has passed away long since, was eager for a fight, and wished to drink British blood before night, but his patriotism was allowed to cool, for before taking boats for the island, an officer sent by the Commodore met us and reported the alarm as caused by some fishing vessels sailing in, which were mistaken for the enemy's boats.”

It wasn’t until July, 1815, five months after peace was declared with Great Britain, that the USS Washington was finally launched as thousands of onlookers gathered along the shore to watch and a band played jaunty melodies. According to local lore, a British spy was arrested at the launch, but it was actually Commodore Isaac Chauncey’s brother who was arrested after being mistaken for an English officer.

The Kittery Navy Yard Strike of 1815

The first shipyard strike in Maine occurred the month after the historic launch of the Washingtonwhen shipbuilders at the Kittery Navy Yard refused to work due to the depreciation of US Treasury notes. Inflation had skyrocketed during those years largely due to disruptions in trade and the government’s reliance on the issuance of paper currency to finance the war effort. Unfortunately, there don’t appear to be any existing accounts of the workers who participated in the strike. Only a brief mention of it appears in a letter written by Secretary of the Navy B. W. Crowningshield dated August 21, 1815.

“If the work of the ship is suspended in consequence measures will be taken to equip the ship in order to proceed to New York, where the payments in Treasury notes are equal to those in gold and silver,” he wrote. “This will eventually drive all the Naval operations and equipment, from the Northern to the Middle and Southern States.”

Black workers also worked at the Kittery shipyard in the early days and likely helped build the Washington, but as Fentriss writes, "orders from the Department caused their discharge and none were allowed to be employed excepting as servants to officers.”

It wouldn’t be until 1941 that Black workers were able to get jobs as skilled tradesmen at the yard due to President Franklin D. Roosevelt's signing of Executive Order 8802 prohibiting ethnic and racial discrimination in the country’s growing defense industry. The order came in response to pressure from Black labor leaders like A. Philip Randolph who had called for a mass rally in Washington to protest discrimination.

The Strike of 1854

In the beginning, the shipyard workers worked from sun up until sun down, but Navy leaders adjusted the hours in the 1840s as shipyard workers throughout Maine and New England were organizing and striking for the 10-hour day. As the shipyard’s commander Commodore John Drake Sloat wrote to Navy Secretary Abel P. Upshur in 1842, "time of work is from sunrise until sunset, except when the sun rises before 7 o'clock or sets after 6 when they commence work at 7 and quit at 6 o clock, not exceeding 10 hours labor at any season of the year." He said ththat wages "are always fluctuating according to the demand for mechanics.” This policy would come back to bite management.

In 1854, as the workforce of 750 was rehabbing the 57 -year old USS Constitutionand building the three masted frigate the USS Santee and the sloop-of-war USS Franklin, the Navy announced a cut in their wages. For the workers, that was the last straw. As the Portsmouth Chronicle reported on December 2:

"A STRIKE: We learn that on Friday morning the ship carpenters and blacksmiths employed on the Navy Yard near this city were informed that their wages from that time would be cut down twenty- five cents per day, leaving the ship carpenters $2 per day and the blacksmiths about the same. When the roll was called after dinner, not one carpenter answered; and it was said that all the blacksmiths were to quit last night. The carpenters are to hold a meeting to consider the matter this forenoon, at 10 o'clock, at Mr. Hayes' on the Foreside.”

The ship carpenters met on December 2 at Hayes’ Hall in Kittery where they adopted a series of resolutions:

- Resolved 1st that we consider the reduction in our pay unjust and uncalled for, and we will not submit to it.

- Resolved 2nd that we view with contempt the conduct of those who continued to work.

- Resolved 3rd we render thanks to the brother mechanics not employed at the Navy Yard, for their sympathy and efficient aid in our behalf.

The group established a three-member committee to set firm wage guidelines for the future. They created another committee to inform the Naval Constructor that they would all resume work at the higher former rate. By December 4, the workers had returned to work after presenting “satisfactory evidence” to the Commodore “that their wages were no higher than was paid in private yards.” The workers also called out a small group of men who scabbed the strike in an ad in the newspaper:

“There were a few who did go to work, against the wish of the great majority — and whose conduct in so doing was strongly censured by the meeting afterwards. Their names were Charles Williams, Wm. W. Brooks, Alpheus Brooks and Ira Delano."

However, the Navy bureaucracy wanted to set an example of the strike leaders. As historian Ray Brighton writes, while the Navy decided to return carpenters’ wages to the original rate of $2.25 per day, it also fired the strike leaders. In response, the workers refused to return to work until the leaders were reinstated. The carpenters, blacksmiths and joiners held another meeting including a representative from each trade at the yard. At the meeting, the workers voted to appoint the strike leaders to go to Washington DC to meet with the Secretary of the Navy to plead their case. Five days later, the Chronicle reported that the suspended workers had returned and would likely get their jobs back. In the end, the Navy reinstated the strike leaders and restored the workers' original wages.

A few years later, shipyard workers were producing warships for the Union Army during the Civil War. By that time, they were building steam-powered battleships and developing submersible and ironclad vessels. The railroad had also arrived and the workers had built a massive floating dry dock. Perhaps the best known of the warships built at Portsmouth Naval Shipyard during that era was the Kearsarge, a steam and sail-powered sloop-of-war that famously defeated the notorious Confederate commerce raider CSS Alabama off France in 1864.

Prior to the 1880s, the winning political party in an election would award federal jobs to their supporters, friends and cronies. That changed with passage of the Pendleton Act of 1883, which created a bipartisan Civil Service Commission to evaluate job candidates on a nonpartisan merit basis. With a more professionalized workforce, workers also demanded to be treated like professionals and began forming unions to fight for their common interests.

Next week: Modern Unions Organize at Portsmouth Naval Shipyard