Labor Day Op-Ed Lessons from the Granite Cutters' Union

A strong labor movement is needed now more than ever

The following Labor Day column by Maine AFL-CIO Communications Director Andy O'Brien ran in last week's Midcoast Villager.

In 1875, a letter appeared in the Rockland Opinion that infuriated General Davis Tillson, a Civil War hero-turned wealthy granite magnate. The letter, written by an anonymous stonecutter, alleged that Tillson kept account of all the voters on Hurricane Island, which he owned with two partners, and made them attend meetings during which he pressured them to vote for his preferred candidates in local, state and federal elections.

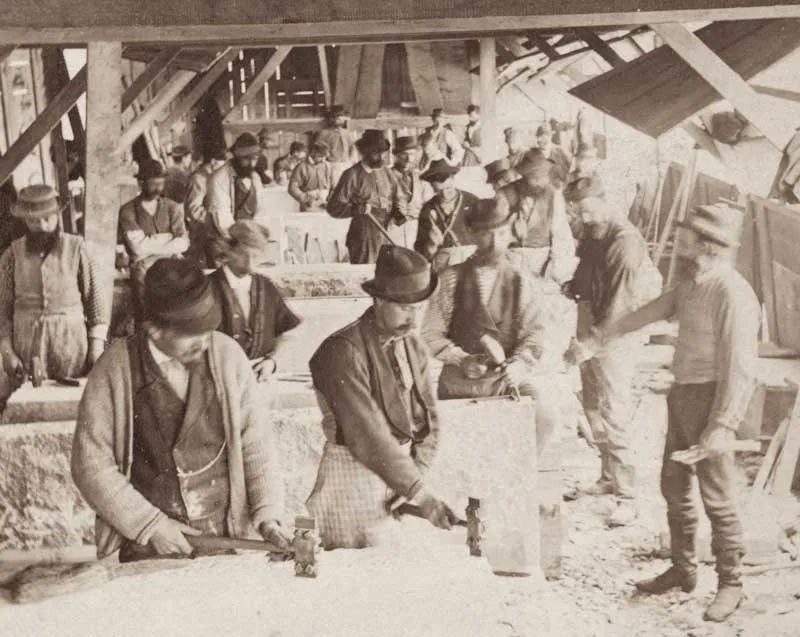

At the time, the island was a classic company town that the general ruled with an iron fist. Tillson was one of four powerful businessmen known as the "Granite Ring” who dominated the granite industry. Cutting stone was dirty, dangerous work and many quarry workers spit up blood in their later years due to silicosis, a respiratory disease caused by breathing silica dust in the poorly ventilated cutting sheds. Children as young as 13 worked as apprentices in the quarries for 50 cents a day. Workers barely broke even because they were coerced into purchasing goods with scrip at the company store.

Most of the blue-collar granite workers were Democrats. However, the letter stated that Tillson told them that his federal granite contracts were dependent on his Republican connections, and “any man who voted the Democratic ticket was his personal enemy.” A stonecutter named P.W. Henrick later testified that he voted for Democrats before working for Tillson, but “democracy has been scared out of me.”

The anonymous letter kicked a hornet’s nest: Tillson soon burst into the offices of the Opinion spewing curses and demanding that the editor give him the name of its author. While the newspapermen didn’t give up the cutter’s name, Tillson had his suspicions. He soon discovered incriminating letters in a trunk in the room of a stonecutter named Timothy McQueeny at a boarding house on the island.

Tillson promptly fired McQueeny, had his belongings thrown into the street, and ordered him to leave the island aboard a steamer to Rockland. The general then announced to everyone in the street that McQueeny was “a convicted thief, liar, reptile, perjurer” and other epithets not fit for print.

“He authorized that any of us who found McQueeny on the island should eject him,” a witness recalled. “That if we hurt him a little it was all right and if we hurt him a great deal he would pay for the damages.”

McQueeny told Tillson he would leave when he was “good and ready” — after all, he paid taxes on the island and had a right to stay.

“To hell with the law,” Tillson retorted. “I own this island and I will be master here. You get off of it.”

Two years later, in 1877, the stonecutters of Penobscot Bay responded to the kind of working environment McQueeny blew the whistle on by forming the Granite Cutters' International Association of America. The union fought for fair wages, shorter workdays, safer working conditions and the abolition of the company store. The momentum of the organized granite cutters was so powerful that a year later they even elected union Secretary Thompson Murch of Vinalhaven to Congress, where he fought for the eight-hour workday. The granite cutters also elected fellow union members to the Maine Legislature. In 1891, they helped pass a state law creating secret ballot elections so prying bosses like Tillson could no longer see how their employees voted.

The Granite Cutters were not alone. By the turn of the 19th century, the Rockland area had become a hotbed of progressive populism and labor radicalism that helped ignite a new era of activism and political reform in Maine. Unionized workers won the citizen initiative, supported women’s suffrage and crusaded against child labor. They formed third parties that called for a minimum wage, a graduated income tax, a national pension system, workers compensation, unemployment insurance, the right to unionize and more. Many of these reforms were later adopted by major political parties and became law. Later, militant organized workers fought for some of our most popular social welfare programs like Medicare, Social Security, Medicaid and more.

At their very essence, unions are about democracy. Being in a union gives workers a stronger collective voice in the workplace to bargain for a fair share of the wealth they create. That collective power extends to our broader society. When one in three American workers were members of unions in the 1950s and '60s, their bargaining power created a more equal and economically just society where more working-class families could afford to live on a single income.

When union manufacturing jobs were offshored and labor laws were scaled back to make it much harder to form unions, their bargaining power rapidly declined beginning in the 1970s. During the same period, powerful elites and their media institutions, increasingly used racism, xenophobia and sexism to divide the working class while right-wing politicians and judges dismantled laws that protect our right to organize together. As a result, working class wages have stagnated while the rich have gotten even richer, even as productivity has risen. We now find ourselves in an increasingly authoritarian society governed by resentment and fear.

At a time when the cost of housing, health care, child care and education are squeezing working families like a vice grip, it’s not surprising that over 70% of Americans support unions. Unions have the potential to unite working people across genders and racial and ethnic lines to see their common economic interests. In order to save democracy unions must be a part of the solution. That’s why it is imperative that we support policies that will create union jobs and reform our broken labor laws to make it easier for workers to rebuild a powerful labor movement — including right here in the Midcoast.