Guest Column: Company Unions and the Ludlow Massacre

by Michael Hillard, University of Southern Maine (Professor Emeritus)

After 1980, union representation took a nosedive as factories closed and union busting became rampant. At the same time, employers started creating “employee involvement” (EI) programs that purported to give workers a new say in the conduct of their own jobs. (I studied this phenomenon in Maine’s paper mills in my book Shredding Paper.) The goal, workers were told, was a collaborative reorganization of work tasks to turn out better products and services, helping businesses remain “competitive.”

Employers promised their workers “mutual gains” – incentive pay and especially in factory jobs a chance to save one’s job from foreign competition. Labor and human resource experts got very excited about these new programs, hailing them for giving workers “voice” at work in a time when unions were disappearing. Some even celebrated them as a return to the “industrial democracy” previously provided by generations of unionized collective bargaining.

A close look at this history raises an interesting twist. These experts, including Clinton Labor Secretary Robert Reich, proposed eliminating the National Labor Relations Act’s prohibition on company unions to give employers a freer hand in setting up EI programs. But another decade would show that these programs offered workers a false promise of a meaningful replacement for union representation, especially as “mutual gains” never materialized. Notably, the Clinton and Obama presidencies failed to deliver labor law reforms that would have restored meaningful workers’ rights.

That liberals would join corporate leaders in pushing for a return of a version of company unions is an interesting case of history repeating itself. A review of this history reveals much about the problematic nature of one side workplace programs created by bosses, where workers don’t have meaningful rights to form an independent, collective voice to bargain with employers on an equal footing – that is to say, legitimate unions.

What were company unions, and where did they originate? The story begins with the infamous “Ludlow Massacre” of 1914. This labor massacre, one of dozens from that era, took place at the Rockefeller owned Colorado Fuel and Iron Company (CF&I). Colorado was one of many Rocky Mountain states then with massive mining operations, dominated by coal but including a host of precious metals and ores – gold, silver, copper, iron, and later uranium. Owners created company–controlled, fascistic regimes where workers lacked civil rights and had to meet all their needs on company terms. As historian H. M. Gitelman described:

Coal mining imposed a degree of vassalage so inconsistent with the American ideal of freedom, that the resort to arms practically was inevitable. The mining camps were situated in isolated canyons. Everything therein, the roads, streets, land, houses, churches, stores, bars, jails, schools, and governments belonged to the company … Discipline was maintained by intimidation and, if need be, by physical assault … coal companies openly flouted state mining laws, rigged elections, and suborned local public officials. Local law officers served them as a private army, enforcing the law selectively in the interest of both the companies and their own perquisites.

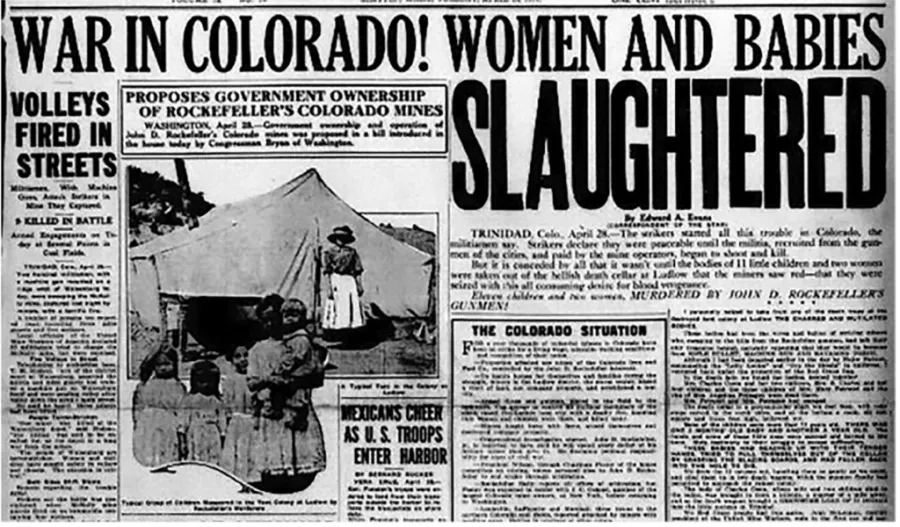

Workers and their families had spent 8 months on strike living in a nearby tent city when an army of state militia and hired guns turned on them. On April 20, company forces started a conflagration in which twenty-three strikers and family members died. Company forces overran the strikers’ encampment and famously doused strikers’ families’ tents with kerosene and then used machine guns to rake the tents and gun down men, women, and children as they fled.

The Ludlow story is important to all who seek the unvarnished truth of US labor history. Engaging accounts include Blood Passionand Killing for Coal. (Read Caleb Crain’s great review of Killing for Coal– a brilliant book that combines environmental and labor history – if you don’t have time for an entire book.).

Not surprisingly, the Massacre changed US discourse and politics. Muckrakers and a Congressional Commission made it the poster child for corporate excess and criminality. The fact that CF&I was owned by the Rockefellers, the nation’s richest family, was pivotal, as historian H.M. Gitelman recounts in The Legacy of the Ludlow Massacre. It raised the bar for employer treatment of workers by giving credence to a new language of “industrial democracy.” US entry into World War I – a war to “make the world safe for democracy” – created full employment, gave workers some bargaining rights, and raised worker expectations for real workplace democracy. However, these hopes were dashed by even more repression after the war. Some 20 years later though, tens of millions of workers were able to bring about real collective bargaining. However, that was only after 20 years of a kind of fake industrial democracy known as the “company union.”

The company union came about because John D. Rockefeller Jr (Junior) was thrust into trying to repair his family’s name. Embarrassed and embattled, the younger Rockefeller hired the best experts in a quest to rehabilitate the Rockefellers’ reputation. This sent him to create an employer-friendly version “industrial democracy” – “employee representation plans” (ERPs) created wholly by management. Junior first set up an ERP at Ludlow in 1915. The company stage-managed its rollout. It unilaterally improved some wages and conditions, gave workers a constitution that spelled out company obligations to create certain better conditions along with committees of workers and managers where workers would have “voice” over safety conditions and certain matters like piece rates. The CF&I “plan” would last until 1933 when it was replaced by the United Mine Workers. (UMW). It gave workers some improvements in conditions, but experts and workers themselves saw it as a weak replacement for a real union.

Junior’s ERP model made him the nation’s first important “corporate liberal.” He heralded it as a tool for creating industrial harmony, improving workers’ conditions, and making unions irrelevant. While Rockefeller did improve his public reputation, his plan was used employers mainly to deter unions coming back after employers quashed the 1919 mass strike.

Hundreds of companies created ERPs in the 1920s. In practice, they gave workers “voice, not power.” Why? As employer funded and created entities, bosses were free to disband ERPs whenever it chose to and often did so if workers demanded too much out of them. They were designed to be weak, forbidding wage bargaining or strikes. Workers’ real problems of compensation, hours, and conditions were structural – occurring at the multiplant employer or industry level. Workers could only match their bosses’ power if they unionized across the company and especially the entire industry. Limiting ERPs to one worksite blocked this. Still hungry for real industrial democracy, millions fought for and gained real unions after 1935.

By the late 1920s, most employers were union free and skipped creating ERPs for fear they would open the door to workers seeking a real union. The ERP made a comeback when workers organized in the 1930s – employers created shell ERPs as part of ruthless union busting campaigns. Congress rightfully outlawed them in 1935.

More recent EI programs are clear descendants of company unions. Still popular amongst employers, they offer “voice, but not power.” In an era of low-wage dead end work, they do not offer a path towards a fairer workplace. Creating a fairer workplace requires a real right to unionize, not more “gifts” from autocratic employers.