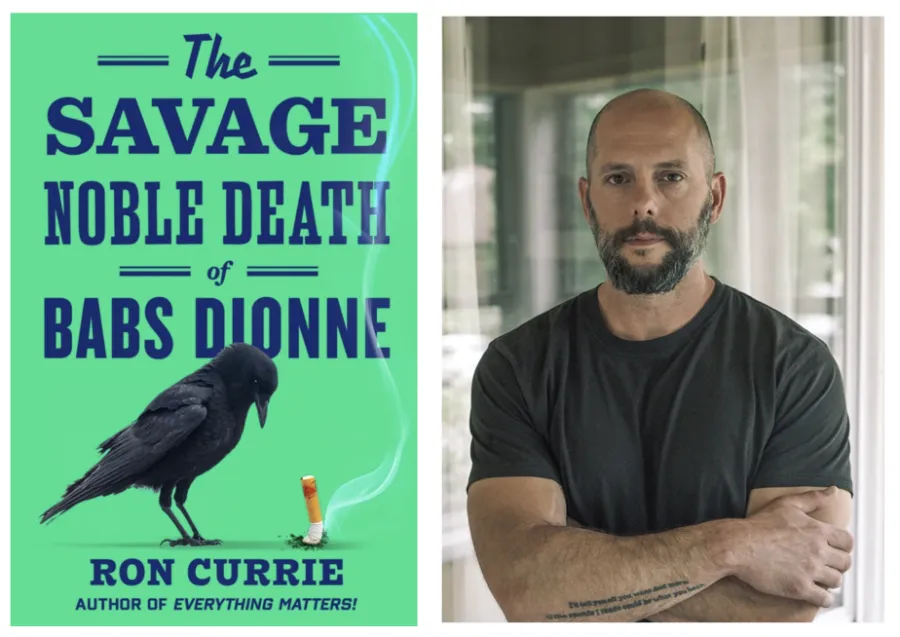

Author Ron Currie Discusses Labor, Franco Americans & His New Novel

Earlier this year, author Ron Currie released his acclaimed new novel The Savage and Noble Death of Babs Dionne about a brash, sharp-witted businesswoman, doting mémère, and ruthless drug kingpin of Waterville’s Franco-American neighborhood. The directors of Stranger Things are developing for a series on Netflix based on the book.

Currie’s crime thriller, set in 2016, is the story of how and why this crime boss controls the flow of drugs into Waterville’s Franco neighborhood, aided by a tight group of sexagenarian lieutenants — Babs’ girlfriends since they were teenagers. The Bollard ran my review of the book in July.

Currie will be giving a free talk on his new book at the University of Southern Maine’s Lewiston campus, 51 Westminster St. in Lewiston, room 170, on September 15, 2025 at 6 pm. You can also attend remotely via zoom by registering here.

Currie grew up in a working class Franco-American household in Waterville. The son of a union firefighter, Currie has written powerfully about the value of unions and collective struggles. When I interviewed Currie in June we discussed his life growing up in a union home and his next two books in the Babs Dionne Trilogy.

“What’s cool about this story is that the thriller is a Trojan Horse,” he told me. “Come for the crime and bloodshed and stick around for the history lesson about being French and Catholic in a Protestant English-speaking state.”

There’s a kind of working class anger that fuels Currie’s creative work. That resentment is especially apparent in his latest novel as Babs sticks it to the tourists and navigates the upper class world of Colby College bigwigs to solicit support for a new French language school. Such an institution, she believes, will prevent her neighborhood from losing touch with its cultural heritage.

“I’ve got a big old blue collar chip on my shoulder, but I also recognize that you can’t be pure in this world,” Currie said. “Can Babs make a play for cultural, economic, religious freedom while also engaging with capital from outside the community to somewhat ironically hold the community together?”

Currie traces some of those class resentments to growing up in a hard scrabble Waterville neighborhood with a “broad sense that everybody was treading water.” His father was a union steward and Currie grew up hearing about issues he dealt with in the workplace.

“He believed in the idea of organized labor very deeply and felt it was very important for the fire department to be a union shop,” said Currie. “They were always fighting battles and putting out fires, as it were, in terms of staffing and city managers’ efforts to churn budgets.”

Currie has written about his father’s struggles with “the corporate jackals” who ran his income insurance program after he suffered a career-ending heart attack at work. The company refused to cover him despite the fact they he had paid into the plan for decades. At 50 years old with only 20 percent of his heart still working, Currie's father lost the modest livelihood he’d built through a lifetime of work.

“I learned two things as I helplessly watched all this going down,” Currie wrote in a 2023 NY Times op-ed. “First, only a sucker bets on a future more distant than his next breath. And second, the difference between being shaken down illegally and being shaken down legally is that instead of going to prison, the crooks in neckties get stock bonuses and gold Rolexes and hearty pats on the back for a job well done.” He added, “Do I sound bitter? Good. I am. Still, after 20 years.”

The strained town-gown relationships in Waterville and Maine’s reliance on tourist dollars from away are also themes explored in his novel.

“I wanted to be able to dramatize the gulf between my intellectual and emotional understanding of what it means to be a Mainer,” he said.

Currie said the second book in the trilogy will be a prequel set during a bitter strike in the 1980s. The story is based on the 1987-88 International Paper Strike in Jay.

“It’s an origin story for Babs in how she became the person we meet in the first book,” said Currie. “When the strike goes sideways she decides that playing by the rules doesn’t work anymore, if it ever did.”

It also explores the long memories of workers in small town communities about their scab neighbors who cross picket lines. The third book, which takes place seven years after the events of the first book, follows Babs’ daughter Lori’s relationship to French speaking immigrants from Central Africa. It will be one of Loris “principle challenges, but also opportunities” in the book, he says.

“I don’t have the experience of being a refugee,” said Currie, “but it strikes me that if you travel half way around the world to a place, a culture, a climate, a topography that is as foreign to you as Mars and then you find that there are people there who speak your language, that’s got to signal home in some way. I’m interested in exploring that in a dramatic way.”

Currie added that it’s unfortunate that so many Franco Mainers hold negative attitudes toward newer arrivals despite being only a few generations away from being immigrants themselves.

“At the very least, the fact that you have a living memory of being descended from immigrants should give your political views a bit of empathy,” he said. “But it feels like a bridge too far for a lot of us.”