“Advocate for the Patient, Get in Trouble:” How Millinocket Nurses Organized Their Union

This article is the fourth part in a series on the history of nurse organizing in Maine. You can read earlier installments here: “We weren’t just fighting EMMC. We were fighting every hospital in the state of Maine.” — A History of Nurse Organizing in Maine.

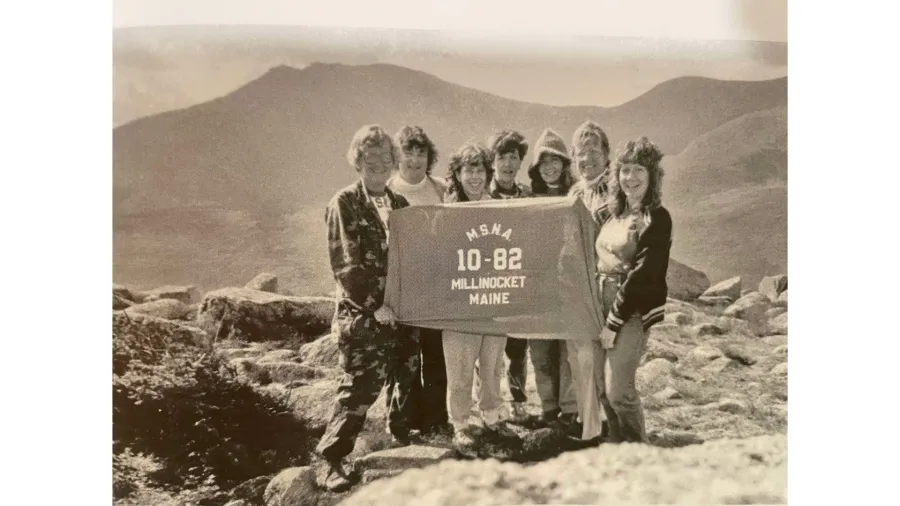

PHOTO: From right to left: RN Terylyn Bradbury, MSNA Executive Director Nancy Chandler, MSNA organizer Polly Campbell & RNs Carolyn Hart, Kristy McGreevy, Kathy Bishop and Faith Flynn after winning their union election.

“Advocate for the patient, get in trouble. Advocate for the patient, get in trouble. This is the way it was every single day when I started working at Millinocket Regional Hospital,” recalls retired registered nurse Cecile Francoeur Martin of South Twin Lake.

Martin said she was “born questioning authority,” so it’s not surprising she emerged as a leader in the movement to unionize hospitals in Maine. A native of Lewiston, Martin could have made more money there instead of up in the remote northern mill town, but she fell in love with a millworker. So at 21 years old in 1968, she headed north to spend the next 46 years caring for patients in the small rural hospital. It was a major change from where she had previously worked at St. Mary’s in Lewiston.

“It was quite a culture shock,” she recalled. “I came from a somewhat progressive hospital for the time to a very small community hospital that was, honestly, 15 to 20 years behind where we were in the cities. When I came to Millinocket I didn’t feel like they really recognized us as nurses.”

Martin was the youngest of a very few young nurses the hospital. She found it hard to fit in at first in the insular mill town.

“It didn’t take me too long to figure out that small towns were very different from cities,” said Martin. “I was an outsider. I mean I married a guy who had been there since he was ten, but I was still considered an outsider.”

The pay was also much lower than what she was used. Eventually she learned that nurses’ aides with much less education were earning more than she was because they had worked there longer. The system didn’t differentiate between registered nurses, LPNs or nurses’ aides on the pay scale. It was a deeply conservative hospital and nurses were expected to know their place in the hierarchy. All of the RNs were required to wear the all-white matching nurses’ cap, nylons and dress ensemble.

It wasn’t long before Martin got in trouble for speaking out about working conditions. She was scolded when she pointed out that nurses’ aides were doing duties that were supposed to be reserved for professional RNs.

“It was not easy. I was a team of one at that point,” Martin recalled. “That went on for two or three years and then a couple more newer nurses started to come in and they were about as uncomfortable with the system as I was.”

When she became pregnant with her first child, Martin was ordered to go home after six months because it was believed that women’s brains didn’t function as well while pregnant and she needed to prepare for birthing.

“Can you imagine telling a young woman today that they can’t work past six months because she’s not able to and probably won’t be able to think as well because of all those ‘hormones?’” said Martin. “That’s ridiculous.”

Women were not considered to be breadwinners in the eyes of society, especially in a town where most of the men had decent jobs at the paper mill.

“Even if you worked, you were still primarily expected to be a mother,” said Martin. “Women were not expected to make career choices that were important to them.They were expected to make career choices that fit the expectations of the time.”

That really limited women to a few professional occupations like secretaries, teachers and nurses. Sexism and sexual harassment were also rampant in the workplace.

“There are some stories that I could tell that would make you just stand there in disbelief and I would swear in any court of law that I was telling the absolute truth,” she said. “It was absolutely horrible sometimes.”

Very gradually, a small group of younger nurses got together to push back on management about working conditions and the unfair pay scale. While they were successful in getting the administration to pay them a little more, their wages remained low and other problems persisted. One day, Martin complied with a doctor’s order to start an IV and was called into the director’s office. The nursing director threatened her with termination for supposedly violating the law. Martin asked what law she had violated and was informed that only doctors could start IVs.

“I said, ‘I think your wrong,’” she recalled. “I knew this wasn’t a violation of the law because at St. Mary’s I was running around with a nurse just doing IVs all day long for a while and I became proficient.”

She then wrote to the Maine State Nurses Association, which was also a trade association that advocated for proper nurse licensing and professional standards, and provided a detailed account of what happened. The MSNA President wrote back to the hospital that indeed Martin had not broken any law and that it should allow RNs to start IVs. However, it wasn’t long before Martin was again threatened with termination for protesting an order to do anesthesia on obstetrical patients because she wasn’t a licensed nurse anesthetist.

“They were insistent that all of the other nurses were doing it and I was going to do it. And I said ‘No, I’m not going to do that,’” she said.

Once again, Martin wrote to MSNA and it wasn’t long before the hospital hired its first certified registered nurse anesthetist (CRNA). She remembered clearly that it was 1971 because that was the year her son was born. She became one of the first patients in Millinocket to have an actual CRNA administering the anesthesia instead of a registered nurse without the proper training or licensure.

“I made a lot of waves, but by then they weren’t pushing back as hard as they used to,” said Martin. “They had a new director of nursing and they recognized that the nurses were starting to get more assertive.”

Even Millinocket wasn’t immune to the larger social currents happening. By that time, the women’s rights movement was surging as women across the nation demanded equal rights, better opportunities and greater personal freedom.

“The women’s rights movement influenced me and I had an influence on it as well,” said Martin. “I’ve always been assertive and I never thought being female meant being subservient. I’ve always seen myself as a collaborator.”

She started making symbolic gestures to show her autonomy. When she returned to work full-time after her second child was born, Martin decided to ditch the dress for a pantsuit and soon other younger nurses followed suit. Doctors made derogatory remarks and management didn’t approve of the new outfits, but the nurses weren’t going back, even though they continued to wear their white caps and shoes. Then one day, Martin decided she had had enough of wearing the cap. Soon the director of nursing called Martin into her office.

“‘When you come to work tomorrow, I want to see that cap,” said the director.

“Tomorrow you will see my cap,” Martin replied.

The next day, she went to work in the intensive care unit and laid her cap on a desk. When the director came in and asked her if she was planning to put it on, Martin replied, “‘No I thought I’d leave it there for my whole shift and at the end of my shift, you can tell me who was more productive: me or that cap.”

No one was ever asked to wear a cap again. Other nurses followed Martin’s example except one who wore the cap until the day she retired.

“She really loved her cap. She felt she worked very hard for it and for her it was important and we supported her,” said Martin. “I never felt that nurses should remove their caps because I took mine off. I removed mine as a symbol that nurses needed to move forward and make decisions based on patient care and not outward symbols of what they thought a nurse should be. In my mind, nursing was changing and I wanted that to be a symbol of change.”

Around 1976, Martin returned to work on a regular basis now that her children were older. The same year, nurses at Eastern Maine Medical Center voted to unionize and she started talking more with her coworkers about working conditions. The pay-scale was still sub-optimal and they agreed that they needed a stronger voice in patient care.

“We needed to get away from that modality where the physician was viewed as a paternal figure who told you what to do and you just kind of went out and did it,” said Martin. “I wanted it to become a collaborative thing where it was two professions working together for the greater good of the patient.”

Martin began writing page after page of grievances and her group began meeting with the hospital administrator to discuss how to resolve them. They made a little headway on wages, but it still was not enough. Doctors and management strongly opposed giving RNs protections from firing for following rules, regulations and laws that governed their profession.

“We were dealing with newer nurses who were a little bit more progressive and physicians who were brought up the traditional way. So things were not going well,” said Martin.

Then along came a young nurse from a tobacco farm in Ontario named Terylyn Bradbury. There weren’t many nursing jobs in Canada in the early 1980s, so she joined a traveling nurse company in the US. She had first worked in Nevada, Texas and Cleveland before landing a gig at Eastern Maine Medical Center in Bangor in 1980. The new union at EMMC had just finally won official union recognition in court and were ready to begin bargaining. Bradbury joined the union as soon as she began working there.

From there on out, she made a commitment to herself to never cross a picket line as a traveling nurse. She had planned to go to Hawaii for her next gig, but after falling in love with a young man from Millinocket at Mardi Gras she ended up back in Maine at Millinocket Regional Hospital subbing for nurses on their summer vacations. It was a much different working environment than at EMMC and other hospitals where she had previously worked.

“Even in 1980 they were quite a bit backward in not giving nurses any kind of independence like we have now,” recalled Bradbury.

Martin was immediately intrigued when Bradbury told her about the union in Bangor. It wasn’t long before they met with Maine State Nurses Association member Dottie Barron, who had led the unionization effort s at EMMC, to discuss organizing Millinocket.

One of the major issues was that step increases stopped after five years, so most nurses all earned the same after reaching the fifth year. There weren’t many male nurses but there was one in the emergency room who earned well over the pay scale of the female nurses.

“He wasn’t in favor of the union. Imagine that!” laughed Bradbury. “He was negotiating his own contract.”

With only about 30 nurses in the bargaining unit, it was a smaller organizing campaign than at EMMC. It also helped immensely that Millinocket was a strong union town. Most of the nurses were married to union millworkers, so they understood what unions were about. They knew that the community would not look kindly on the hospital if it waged a scorched earth anti-union campaign like EMMC had.

“I don’t think they really took us seriously. I think we took them by surprise,” said Bradbury. “I think they thought just a few of us were pushing things and the rest were going to vote no.”

In the end, the union won in a landslide victory and MSNA Local 1082 was official. Bargaining the first contract went relatively smoothly. Bradbury said it helped that it was a small hospital where everyone knew each other and had friends on both sides of the bargaining table.

“We were very fortunate in that getting that first contract went a lot smoother than I thought it would,” she recalled. “We all agreed to do the best we could to get a contract nailed down and build off it in the years ahead. We allowed people to get what they needed instead of having to beg for it or kiss up to someone.”

Bradbury said that while the nurses didn’t get “the sun, moon and the stars,” they did win better wages and a pay scale. It gave RNs broader professional autonomy and the ability to advocate for their patients without retaliation. Full-time nurses were also given preference in hiring over traveling nurses.

The one sticking point was language the nurses proposed to include “significant other” in their bereavement policy because Bradbury wasn’t yet married to her longtime companion. A nurse supervisor on the management side grumbled, “She’s living with him. Why doesn't she just marry him?” Bradbury did marry him eventually and they raised a family together. She became the local’s first President and Martin its longtime chief steward.

“I always liked that position because I got to write a lot of the wording in the contract, if not most of it,” said Martin. “I got to negotiate directly with the MSNA leadership as well as hospital leadership and I enjoyed training younger stewards.”

She served as president for a little while, but didn’t like it because she didn’t have much power besides presiding over meetings. The vice president was where the real power lay, she said, because the VP was the chief negotiator. In addition, she held various positions within the statewide union and taught workshops to other nurses about how to become strong patient and nurse advocates.

Bradbury served as both president and chief steward at various times throughout her 35 years at Millinocket Regional Hospital. She retired in December, 2021 after 44 years at the bedside. On her last day of work, she dug out her old nurses’ cap and cleaned it up as best as she could. She wore it all day as management and her coworkers honored her for her long career of caring and advocating for patients.

“Now I’m living the dream,” she said. “The only unfortunate part of my dream is that my husband passed away so he’s no longer with me living this dream, but other than that I’m doing fine.”

Her advice to younger nurses is to avoid taking management’s word for it when it comes to their contract. She says rank-and-file RNs need to read their union contract and seek out their stewards if they have questions because it’s easy to misinterpret language.

Martin worked in the field for 46 years before retiring on Dec. 12, 2013 — a date she remembers clearly because she marks it on her on calendar every year to remind herself. Even after retirement, she has continued to be very active in supporting labor causes and advocating for Medicare for All.

Martin and Bradbury have seen many changes over the years, including the loss of Great Northern Paper and the shrinking of the hospital workforce. They’ve watched with alarm as deindustrialization and the political war on workers’ rights has decimated the ranks of organized labor. They both agree that lack of patient staffing has become a crisis and the state must pass legislation requiring safe nurse-to-patient ratios in hospitals. Bradbury said that her son-in-law is an RN, but had to leave the position he loved in the ER because he was worried that having too many assignments could put his license at risk.

“We’ve got to fix this somehow because we have enough nurses. We just don’t have enough nurses who want to practice nursing and take care of patients because of the working conditions,” said Bradbury.

Martin says she also worries that too many RNs are leaving the profession or becoming nurse practitioners because they don’t want to deal with the stress of being bedside nurses. She has experienced first-hand the decline of rural health care. She and her husband live on Twin Lake in an unorganized territory outside Millinocket and they are finding that they have to increasingly travel to Bangor or out of state for specialists. Their primary care physician will also be retiring soon so that also means they will probably have to drive an hour and a half to Bangor for primary care.

“I think we need universal health care and I am as forceful in that belief today as I ever have been,” she said. “I think it is wrong, wrong wrong to have a tiered system of health care like we have in this country.”

Bradbury says the union was the best thing to happen to nurses at Millinocket and other parts of the state, but she worries that some may take the hard work and sacrifices of their forebears for granted.

“I think what happened after years and years of good contracts and making good money, people get a little complacent and younger nurses don’t know how hard it was for us to win our unions and hold onto them,” she said.

Martin Agrees. “I have that discussion with my grandchildren today on why they’re going to lose what we worked so hard for if they don’t step up to the plate. For all women all over America. I don’t want to go back to where it was in the 1950s and the 60s.”