“We weren’t just fighting EMMC. We were fighting every hospital in the state of Maine.” — A History of Nurse Organizing in Maine

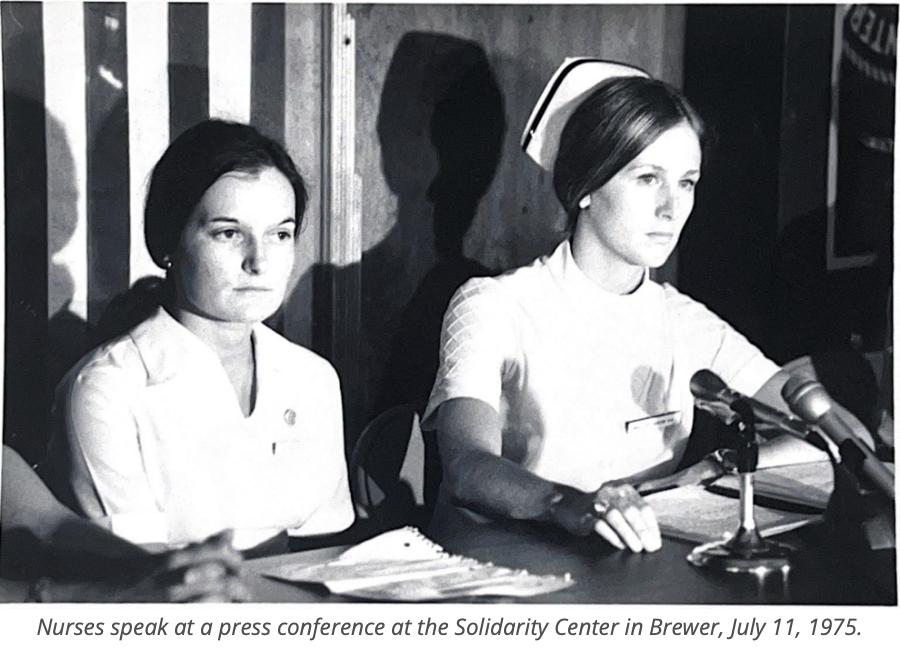

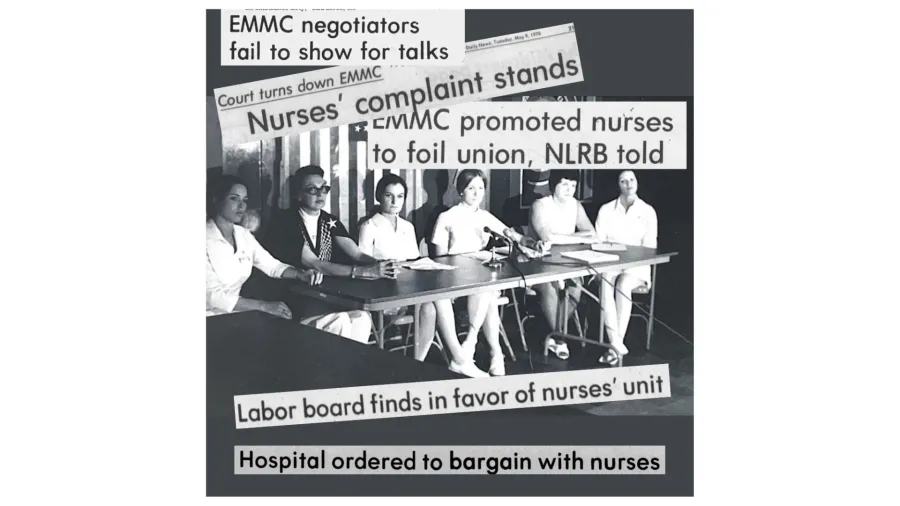

PHOTO: EMMC registered nurses announce their effort to form a union on July 11, 1975.

One day Dottie Barron, a registered nurse at Eastern Maine Medical Center in Bangor, was called into her supervisor’s office. Her first thought was, “Oooh! Somebody is doing something!” What she heard next filled her with excitement. The supervisor wanted to know if Barron knew anything about an effort among some of her colleagues to form a union.

“The funny thing is, long before I ever heard anybody say anything, I used to say, ‘Jeez, what we need around here is a union,’” recalled Barron. “When I was called into management’s office about the union, I guess she pegged me as interested, but I hadn’t gotten the word yet because they were trying to be very low-key. I just listened to her and said, ‘Oh?’ I really hadn’t heard anything at that point. So I left that meeting and thought, ‘hmm…I wonder who is safe to talk to and I started asking people questions. Then I found the right person and away I went.”

The next thing Barron knew she and her union sisters were holding a press conference at the Labor Temple (now called the Solidarity Center) in Brewer to announce the formation of their union.

“For too long the registered professional nurses at the Eastern Maine Medical Center have been frustrated with their ability to function at the level for which they have been prepared,” said Patricia Martin, the chairwoman of the organizing committee. “Therefore, these registered professional nurses feel that now is the time to take a positive and progressive step forward by joining together to form a collective bargaining unit; a first for the State of Maine. The primary purpose: quality patient care.”

It was July 11, 1975 and the scrappy group of nurses would go on to win the first union election at a hospital in the State of Maine.

For the nurses, wages weren’t the driving issue, although they were indeed fed up with being paid less than men. They wanted more involvement in defining patient care programs and better in-service education, personnel polices and practices around staffing assignments and communication between management, physicians and nurses. Most of all, they wanted a collective voice to improve patient care. The nurses claimed 45 percent of the 200 eligible RNs at the facility had pledged their support for the union

Barron grew up in Millinocket, which was then a union stronghold. Her father was a union man and worked at Great Northern Paper, so she knew first-hand the benefits of union membership. She was about five years old when she began thinking about becoming a nurse when she grew up. She remembers asking her mother what the workmen down the street were building. Barron's mother told her it was a hospital and described all of the good work the people inside the hospital do to make people well again. Upon graduating high school Barron enrolled in nursing school in Bangor and got her first full-time job at Eastern Medical Center after graduation in 1971.

In those days, short staffing wasn’t as much of a problem as it is today. She worked in an all-female medical ward with four bedrooms and would float back and forth between the mixed unit and the all-male ward below depending on where she was needed.

“Things were a lot less technical,” she recalled. “I hate to say it this way, but people didn’t survive back then who survive now because of technology.”

But she was also frustrated with the way nurses were treated and the unfairness of how work schedules were doled out. If you were close friends with supervisors, you got the raises and promotions. If you weren’t, you didn’t. Standards and expectations widely differed depending on which department you worked in and who your supervisor was.

“I felt there really needed to be some fairness and there wasn’t,” said Barron. “It didn’t matter what we said. They didn’t see us as bringing in any money. Everything revolved around the physicians.”

As Barron recalls, these long simmering grievances boiled over after an intensive care nurse with excellent reviews and impeccable credentials was fired because a physician didn’t like her. Shortly after, a nurse got a group of her close colleagues together for a spaghetti dinner to discuss forming a union and the movement grew from there.

A Very Brief History of Nurse Organizing

Following passage of the 1935 National Labor Relation Act (NLRA), which set up the process for union elections and required companies bargain with unions, there were a few successful nurse union drives here and there. But the 1947 Taft-Hartley Amendments to the NLRA passed by Congress excluded workers at private nonprofit hospitals from collective bargaining rights . In 1962, President John F. Kennedy issued an executive order allowing workers at Federal hospitals to unionize. In 1966, workers at the Togus VA Medical Center in Augusta defeated an independent union at the ballot box and formed American Federation of Government Employees (AFGE) Local 2610.

In the meantime, twelve states (not including Maine) passed laws granting nurses at private non-profit hospitals collective bargaining rights. It wasn’t until 1974 that Congress amended the NLRA to expand these rights to health care workers nationwide. At the time, the Maine State Nurses Association (MSNA) was a professional organization affiliated with the American Nurses Association (ANA). Founded in 1896, ANA’s historic mission has been to protect the interests of nurses and improve nursing education and professional standards. It also occasionally joined the fight for labor rights like the eight-hour day. Gradually, ANA began to get into labor organizing as nurses gained collective bargaining rights. With the support of MSNA and ANA, the EMMC nurses developed a list of objectives for their new union and began organizing.

“None of us really knew what to do in the beginning,” said Barron in an interview for the book Maine Nursing: Interviews and History on Caring and Competence. "The American Nurses Association sent people to help us, figure out what we needed and how to get things going, how to get organized. We received a lot of help from other unions in the area. They were very helpful in terms of meeting with us about organizing and letting us use facilities for free. We had no money.”

The Maine AFL-CIO, Teamsters Local 340 and the local MEA teacher's union came to the union's aid, providing them with a meeting space and use of a photocopier.

In Come the Union Busters

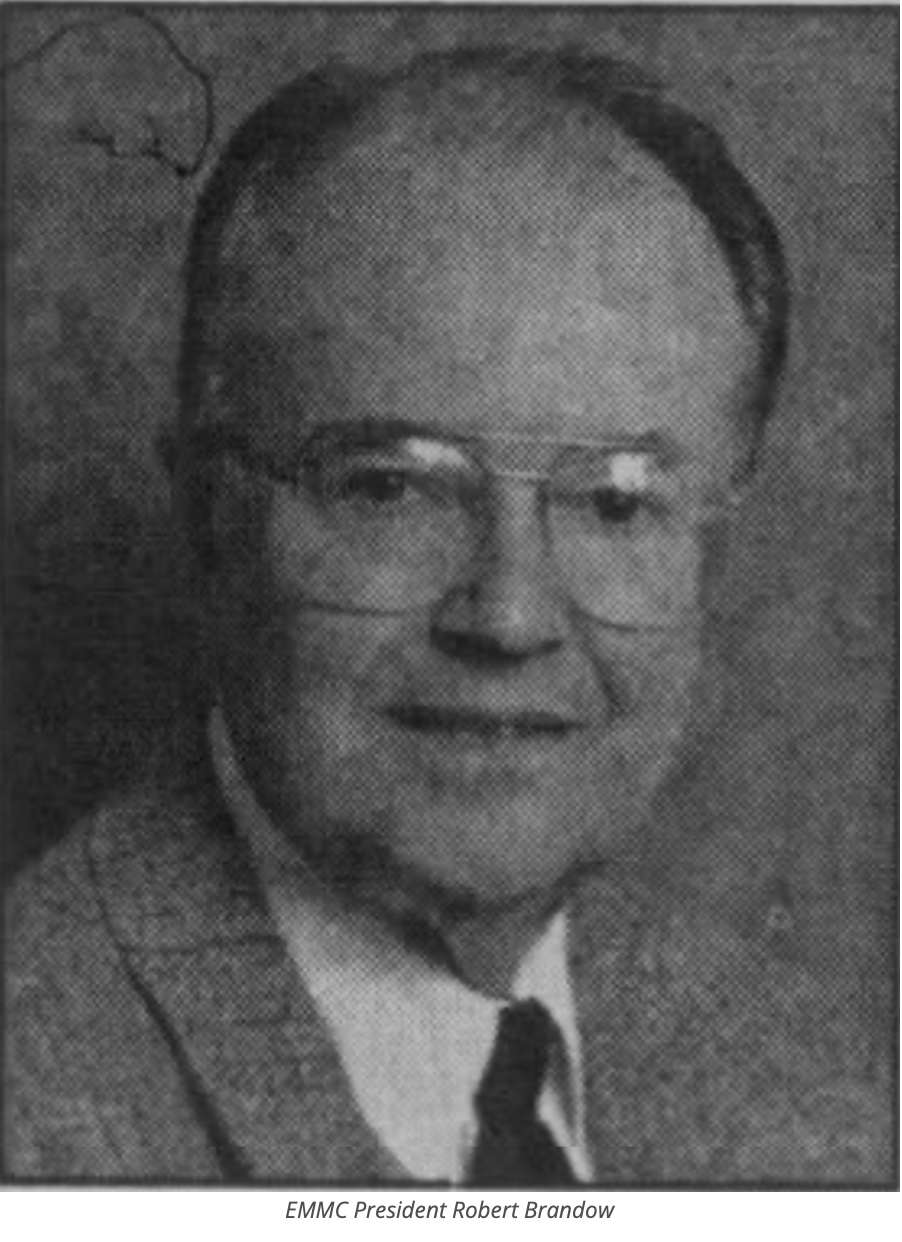

However, the EMMC Board of Trustees and President Robert Brandow were not about to let a rag tag group of nurses build power in their hospital. Brandow joined the hospital as its first administrator with hospital management experience in 1969 and soon made a name for himself as a change agent.

As the Bangor Daily News noted in a tribute following his death in 2021, modern hospital administration was in its relative infancy in those days. Brandow applied his skills to oversee the hospital’s expansion, streamline operations and take its budget out of the red. He was also instrumental in creating the precursor to what is today the Northern Light health care system, a sprawling network of ten hospitals throughout the state.

A Northern Light spokesman remembered Brandow as a “visionary and gifted businessman.” But his corporate vision for the hospital did not include unions and he would do whatever it took to prevent them from taking root, even stretching the boundaries of legality. All of the other hospital administrators in Maine were tensely watching the events unfold at EMMC because they knew if MSNA won this round, they would be next.

Brandow was prepared to spend thousands of dollars to defeat the union and immediately hired the services of the notorious Modern Management Methods, known as 3M, the largest union busting firm in the country at the time. With over 70 employees, 3M took on roughly three dozen anti-union campaigns a month, specializing in health care, universities, banks and insurance companies. Its consultants received per diem fees of between $500 and $800 a day ($2,700 to $4,300 in current dollars adjusted for inflation ), plus expenses.

“Oh they were spending megabucks on union busting companies. We were fighting the world,” Barron recalled chuckling. “Just some nurses.”

One of 3M’s most famous consultants was Martin J. Levitt, who detailed the company’s unethical tactics and use of deception, intimidation and dirty tricks in his tell-all memoir Confessions of a Union Buster. As 3M founder Herbert Melnick told the New Republic in 1979, front-line supervisors were 3M's “primary tool” against union drives. They would misleadingly convince supervisors that a victory for the union would jeopardize their power and make them lose their ability to hire, fire and discipline workers. If the supervisor wasn’t willing to do the dirty work, they would find one who could and reward them for their loyalty.

Armed with stacks of anti-union literature, the supervisors were ordered to hold as many as 25 one-on-one meetings with each employee and report back to the consultant daily about the workers’ reactions. They also helped the anti-union workers organize against the union. Barron said that unlike the pro-union nurses, the anti-union nurses “seemed to have all kinds of free time” to talk to their coworkers while they were supposed to be on duty.

“There’s not a doubt in my mind that they were being paid by the hospital to organize against the union,” she said.

3M’s signature tactics including firings and suspensions of union activists, surveillance, interrogation, isolation and harassment of pro-union workers with a constant flood of half truths and anti-union fear mongering. The opening salvo in 3M’s anti-union campaign against EMMC nurses was a letter informing them that the Board of Trustees “feel the best interest of the patients will not be served if the nurses turn to an outside party to represent them.”

“We understand Maine has been designated by the nursing association as a pilot or target state in a nationwide strategy to unionize nurses,” wrote Brandow. "This commitment of resources at a national level has come to the attention of the general public before, in the strike in San Francisco last fall.”

The inflammatory letter had 3M’s fingerprints all over it, from portraying the nurses’ union as a malevolent “outside party” to spreading fear that they would “lose their rights to the union.” MSNA soon filed a unfair labor practice with the NLRA over the “coercive and intimidating” letter. The nurses vehemently denied that the union drive was part of some kind of national effort. They were aided by a consultant from the American Nurses Association, but she had nothing to do with a strike in San Francisco.

“This is a direct attempt at the administration to subvert the legal rights of nurses to engage in the organizing process.” Said Shirley R. Knowles, MSNA spokesperson at an August press conference at the Labor Temple in Brewer. She added that the ANA consultant “who has been in Maine at our request for a total of four days in last five months, was never involved in the organizing effort in San Francisco. Mr. Brandow would be well advised to carefully check his sources before he repeats such wild rumors.”

The nurses denied that the EMMC RNs were getting any “money whatsoever” from ANA. MSNA’s Executive Director Patty Martin added, “We’re out selling bumper stickers to raise money” while the administration dips into petty cash to send money to all the nurses.”

Meanwhile, 3M’s deliberate strategy of sowing fear and confusion was creating an ever more toxic work environment. After learning that Barron was the “doing all the noise making and organizing,” a male neurosurgeon angrily confronted her.

“He came down the hall screaming, screaming at the desk. I couldn’t talk or say anything. And he got madder and madder and madder….we never did get along,” recalled Barron laughing. “I went through a lot of mostly yelling abuse. [The doctors] could do anything. Part of his problem was unions and part of his problem was women. Where he came from women didn’t really matter that much.”

Nevertheless, the nurses didn’t let the union busters distract them and continued quietly organizing. The mother of one of the nurses made blue ribbons for the RNs to wear and show their support for the union. They quickly learned their rights and what activity was protected and what wasn’t. They placed leaflets in non-patient areas, like on the backs of bathroom doors, though management followed closely behind, tearing them down as fast as they could put them up. One time Barron and some of her colleagues were thrown out by hospital security after they tried to catch nurses going off the clock and coming in for night duty at the shift change.

But filing for their union election also gave them some protections from retaliation. Barron remembered that one nurse, “a sweet little southern gal” who did not support the union, tried to call in sick one day. However, her supervisor demanded that she come to work anyway. She looked “deathly ill” as she dragged herself into work and asked Barron for a blue ribbon.

“She never got hassled again,” said Barron. “Whether she was pro-union or how she voted I don’t know, but they learned if they thought she was [pro-union] they weren’t going to hassle her.”

But they weren’t able to win over all of the nurses.

“What used to really kill me was when a nurse would say, ‘my husband says I can’t do this,’” said Barron. “Oh my God. Give me a break! My mother voted Democrat and my father voted Republican their whole lives and they got along.”

Barron thought the nurses should delay the election date so they could have more time to organize and build power, but others were antsy to get it over with. As the nurses mobilized, the hospital had also organized a squad of anti-union nurses to drive turn out.

“If they knew you were pro-hospital, by God they’d go and get you and bring you in on your day off to vote,” said Barron. “They had a whole group of anti-union nurses.”

When all of the votes were counted on March 19, 1976, the union won by just fourteen votes, 114 to 100 out of 226 eligible voters. Speaking to reporters, MSNA member Shirley Gallagher of Bangor said, “We’re very happy.” However, she added, “the vote was closer than we anticipated.”

Brandow responded that he was “glum” with the election results, but it was clear that the hospital was “obligated to work together cooperatively to see that the highest ideals of patient service are maintained throughout all future negotiations.”

The pro-union nurses had won the first round, but the fight was far from over as there were still plenty of opportunities to derail negotiations for the nurses’ first contract. A few weeks after losing the battle at EMMC, 3M successfully thwarted a union drive at Maine Medical Center in Portland and it was just getting warmed up for another fight at EMMC. It would be another five years of legal fights, hearings, a decertification and a recertification of the union before the EMMC RNs would win their first contract.

EMMC Nurses & The Five-Year Fight to Win Union Recognition

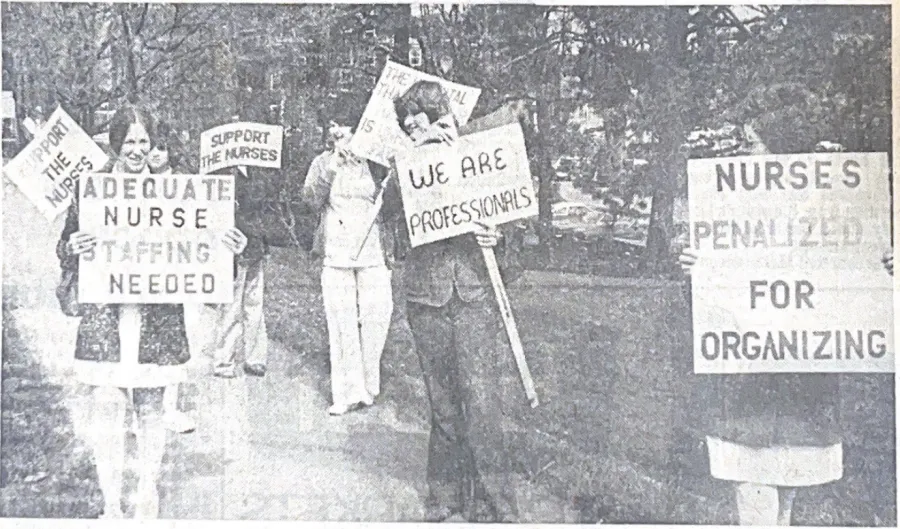

PHOTO: EMMC nurses picket outside the hospital in April, 1977.

This is part two in a series on the history of nurse organizing in Maine. You can read part one here.

When nurses at Eastern Maine Medical Center in Bangor won their union election by 14 votes on March 19, 1976, that was the “easy” part. They couldn’t imagine that it would take another five years of legal wrangling before the hospital was finally forced to bargain with them by court order. After being publicly embarrassed by the victory, EMMC’s Board of Trustees, its President Robert Brandow, and his hired anti-union consultants weren’t about to give the nurses an inch.

The Businessman's Board

The EMMC Trustees included representatives from some of the largest and most anti-union employers in the state. They included Chairman Doug Brown, President of the Doug’s Shop ‘N’ Save grocery chain; Ralph E. Leonard, Chairman of contractor H.E.. Sargent Inc., and Clifton G. Eames, President of N.H. Bragg, a Bangor industrial equipment supplier. Other members included the presidents of Bangor Savings Bank, Merrill Trust Bank and Merchants National Bank as well as the vice-president of the Dead River Oil company, a Republican legislator and lawyers with the firm Mitchell and Stearns and Eaton Peabody, the hospital’s employment attorney.

Perhaps most striking, given the negative coverage the nurse’s campaign received in the Bangor Daily News, was that EMMC’s board also included Arthur McKenzie, vice president, treasurer and general manager of Bangor Publishing, the parent company of the BDN. This was a fact briefly mentioned in the paper at the time, but not McKenzie’s connection to the newspaper.

Brown had served on the Bangor City Council as well as several community boards, from EMMC and the University of Maine Foundation to Husson College and the Governor’s Business Advisory Council. He liked to say that his business philosophy was “to take care of the customer first, the employees second, and the stockholders third.” But in practice, Brown was ruthless when it came to labor disputes at his stores, which Hannaford Brothers owned a majority stake in.

Five years earlier, workers at Doug’s Shop ’n’ Saves in Bangor, Brewer, Old Town, Ellsworth, and Bucksport organized a union after Brown forced six employees to submit to a polygraph test when some stock went missing. Brown’s refusal to agree to a union security clause provoked a long, bitter strike that was marked by court injunctions against picketers and an alleged plot to firebomb a Waterville supermarket. In the end, Brown defeated the workers and they returned to work eight months later without a contract. During the struggle for union recognition at EMMC, nurse Dottie Barron and several of her coworkers refused to shop at any Doug’s Shop ’n’ Save stores.

“There weren’t many of us who didn’t shop there anymore and I’m sure it didn’t make any difference, but politically I just couldn’t do it,” said Barron.

Brandow and the EMMC trustees followed a similar strategy of stonewalling in negotiations with the nurses, often postponing bargaining dates and even failing to show up for scheduling sessions. After more than a year, the two sides still had not reached an agreement. Meanwhile, the administration approved raises for other non-union employees, effectively providing fuel for the anti-union nurses who had collected enough signatures to hold another vote on the union. Some of the clinic nurses issued a statement to the press announcing their disapproval of the collective bargaining effort.

Pro-union nurses struggled to get their side heard because company rules prohibited them from talking to other nurses about the union, even when they were off duty and in non-working areas. The Bangor Daily News seldom ran pro-union letters to the editor. Eventually Barron and a group of nurses got together and made an appointment to complain to the newspaper’s editorial board.

“We’re sitting up in a balcony-like office and they’re saying ‘oh no no, we only print so many of everything that comes in' and we’re like ‘well how come none of the nurses’ letters are being printed?” recalled Barron. “Suddenly, the hospital’s lawyer comes bursting in downstairs screaming, ‘‘Who the hell wrote this article?!” not knowing there were about eight of us nurses sitting upstairs with the administrator on the balcony. We had one reporter who, when she could, would write what I called a ‘fair article’ [about the EMMC nurse campaign].”

Barron said the reporter later told the nurses that she “had to be careful” or she would get fired for what she wrote.

“Oh yeah, they owned the Bangor Daily back then…. But we did get a few nurses’ articles in the next two weeks,” she added.

A De-cert and a Re-cert

PHOTO: EMMC RN Christine Harrington demonstrates at a picket. Photo by Jack Loftus

After a mediator declared an impasse in bargaining in February, 1977, pro-union nurses organized their first informational picket to call for a fair contract. In response, Brandow had letters delivered to the hospital’s 300 patients bad mouthing the nurses as “unprofessional” and unethical. The hospital expressed “grave concern over the psychological impact the picket could have on the patients.”

“Say you’ve got a woman from Millinocket with a child year,” hospital spokesman James Coffey told reporters. “She has to work. While this [picketing] is going on, she’ll be asking herself, what is going to happen to my loved one down there in Bangor at EMMC?”

The administration also sent telegrams to MSNA leaders falsely declaring the informational picket “illegal” and threatened to file a complaint to the NLRB if they did not cease immediately. Speaking to reporters, the MSNA local President Pat Martin dismissed the letter as “another tactic to try and scare us.” When asked by the Bangor Daily News to comment on the hospital’s claims that the picketing was psychologically harming patients, Martin vehemently disagreed.

“Most of the patients were not even aware of it until the hospital dragged it up for them,” she said. “It’s nonsense."

The hospital even sent out staff to photograph nurses on the picket line, which many of them saw as an act of intimidation. Retired nurse Dottie Barron recalled standing on the picket line when a man drove up in his car.

“He points up to his administrative office in the older part of the hospital and says, ‘They’re all the same. They’re on boards of the banks. They’re on the boards of both hospitals. They’re on the university [board]. Those people don’t care.’ He got back into his car and he drove off. It was true.”

At the end of July, 1977, the EMMC nurses voted 132-81 to decertify the union and leave the Maine State Nurses Association.

Union President Pat Martin attributed the results to the collective bargaining process taking too long because of the lack of across the board raises and “because the hospital hired two consultants and two lawyers, and conducted a daily campaign to discredit nurse organizing.” Martin noted that the administration had the backing of the powerful Maine Hospital Association, and that EMCC had paid the cost of flying four nurses back from vacation in order to vote.

But the fight wasn’t over. The nurses filed several unfair labor practices against the hospital charging that it failed to bargain in good faith, withheld wage increases to discourage union activity, unfairly prohibited off-duty nurses from advocating on behalf of the union in non-working areas of the facility, and interrogated prospective nurses on their views of the union.

A year later in October, 1978, Judge Robert A. Giannasi, an administrative law judge at the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB), invalidated the decertification election because hospital officials committed unfair labor practices by not bargaining in good faith. The court also found that the hospital illegally prohibited pro-union nurses from soliciting their coworkers to join the union during off-duty hours and in non-working areas and unlawfully withheld wage increases from nurses who supported the union while granting increases to anti-union nurses. The judge called on the hospital to reimburse MSNA for collective bargaining costs incurred during negotiations.

Meanwhile, negotiations were still stalled because EMMC appealed the decision. Barron recalled the stress of being deposed and having to testify at court hearings and the NLRB.

“The whole process dragged on and on and anything they could bring up to stall it happened,” said Barron. “We were all a wreck because we knew we had to testify.”

It wasn’t until August, 1981 that a First Circuit Court judge in Boston rejected the appeal and ordered the hospital to bargain in good faith with the Maine State Nurses Association’s 235 members. MSNA spokesman Patrick Scanlon called EMMC’s appeal “a delaying tactic to postpone collective bargaining in good faith” and an unsuccessful effort to bankrupt the union. While the hospital seemed to have endless resources, the nurses struggled due to having to take time away from work for negotiations and hearings. At one point the nurses had to turn to legal aid because they ran out of money.

“We are absolutely delighted at the court’s finding, and we look forward to sitting down and negotiating in the near future,” Scanlon told the Bangor Daily News.

A month later, the nurses finally received $190,000 in back wages with an average reimbursement of $450 plus $125 interest for withholding raises from union members.

The First Union Contract at a Hospital in Maine

This article is the third part in a series on the history of nurse organizing in Maine. You can read part one here here and part two here.

After a First Circuit Court judge in Boston ordered Eastern Maine Medical Center to bargain in good faith with the Maine State Nurses Association after five years of delays and legal appeals, the hospital finally relented.

Throughout the winter of 1981 and ’82, both sides met for some very heated negotiations. The nurses’ bargaining committee volunteered their time without pay for months as the hospital fought their demands. They often negotiated evenings with a crockpot of chili one of the nurses brought in for dinner. One time, the nurse instructors brought the bargaining committee pizzas. Meanwhile, management and its attorneys were getting paid well to be there and were able to go out to dinner every night.

“It was really a commitment for us because people put in their time, their effort, their money,” said Barron.

But just because the hospital claimed it was bargaining in good faith, that doesn’t they were. After 26 bargaining sessions, a group of nurses, patients, clergy and other community supporters calling itself “Citizens for Quality Health Care” gathered on Monday, June 14, 1982 at the Holiday in Bangor to condemn the EMMC board for its intransigence in negotiations.

“Tonight marks our 27th session and we are no closer to a contract now then we were in January,” MSNA Executive Director Nancy Chandler told the group. Another picket was planned for June 25, the following week. Chandler said a strike was one tool the nurses had if management wouldn’t agree to a fair contract.

“These nurses do not want to strike,” Chandler said. “They are concerned about the quality of health care in this community and continuity of care at EMMC. This is a tool they do not want to use, yet day after day, they are being forced closer to withholding their services.”

Audience members pointed out that bedside nurses knew a lot more about quality health care than the businessmen on EMMC’s Board of Trustees who were failing to act in the best interest of patients, employees and citizens of Eastern Maine in negotiations.

“Businessmen and development people decide the fate of building plans and patient care,” said Anna Gilmore, President of the bargaining unit. “Nurses are merely laborers at this hospital.”

The following week, MSNA filed another unfair labor practice complaint that “nurses were harassed and threatened if they took part in the picketing.” Fortunately, the two sides came to agreement the day before the scheduled picket. On June 24, 1982, seven years after the EMMC nurses launched their organizing campaign, they voted 192-11 to ratify their first union contract at a hospital in Maine. Champagne corks flew in a conference room at the Bangor Ramada Inn after the bargaining team announced the results.

The contract included:

- Pay raises of between 30-35 percent for most nurses over two years, including an 8.5 percent wage increase in the first year and 8 percent in the second.

- Improvements to dental and life insurance

- Pay increases for nurses working nights and weekends

- Sabbatical for faculty at the nursing school after 7 years

- Replacement of holiday, sick and vacation time with a system of planned, earned and paid time off.

- An increase in the discount at the cafeteria from 20 to 30 percent

- Increases to uniform and shoe allowances

But the hospital refused to agree to a union security clause to ensure all of the nurses in the unit paid for the costs of collective bargaining. That was another battle.

“In that first contract we didn’t get everything we wanted,” said Barron, “but looking back and not knowing a lot, other than reading several other nursing contracts from other states, I was pleased with it.”

However, two years later the hospital would once again try to break the young union.

“I think it’s quite evident that they want to push our backs to the wall,” said MSNA President Sandra Putnam in September, 1984 as a strike deadline loomed.

When EMMC Nurses Took on Management in the Struggle of ‘84

This article is the fourth part in a series on the history of nurse organizing in Maine. You can read earlier installments here,here and here.

When it came time for registered nurses to negotiate a second contract with Eastern Maine Medical Center in Bangor, the battle lines were already drawn. It took years of legal wrangling, hundreds of thousands of dollars in fines and a court order to force the hospital to negotiate the first contract. Now, EMMC President Robert Brandow and the local businessmen who sat on the hospital’s Board of Trustees were determined to halt any progress the nurses had made, even if it meant provoking them into a strike and busting the union. The hospital once again brought in its rabidly anti-union attorney Malcolm Morrell to lead negotiations.

“It was a nightmare,” recalled nurse organizer Sue Arcadi, who worked on the second contract campaign. “It was the first time that nurses had organized and voted for a union [in Maine] and they just couldn’t wrap their heads around it. They were just brutal and did everything they could to avoid negotiating in good faith.”

Bargaining began in March 1984 and by June the nurses were working without a contract. Then in September, after six months of bargaining with management and a federal mediator, EMMC nurses voted overwhelmingly to strike. They set up their war room in a former Papa Gambino's pizza parlor temporarily donated by a sympathetic landlord. The space on State Street was humming when a Bangor Daily News reporter stopped by in late September, 1984, just three days before the strike deadline.

“Strike headquarters!” nurse and union treasurer Judy Cushman cheerily answered the phone.

A friendly neighborhood cat stood in the window of the nurses’ emergency headquarters that was filled with donated furniture, old rugs, a coffee pot and office equipment. Newspaper clippings chronicling the months-long struggle with the hospital covered the walls along with a bulletin board of help wanted ads for nurses in the event of a prolonged strike. A chart with lists of days and times to sign up for pickets around the clock was filled with names. One poster had the words “We are not satisfied… the agitation will go on.” Another said, “Pay should equal education and responsibility.”

The Maine AFL-CIO and other unions lent their support to the nurses. Featured prominently on the headquarters walls were messages of solidarity like “Local 10-82 Millinocket supports the nurses of Eastern Maine Medical Center in their struggle for fair pay, fair play and human dignity.”

Teamsters Local 340 vowed that none of its members would make any deliveries to the hospital from UPS, Grant’s Dairy or the St. Johnsbury Trucking Company in the event of a strike.

“I can’t imagine a UPS guy crossing a picket line,” Teamsters 340 President Bob Piccone told the Bangor Daily News.

In a letter, Piccone told the nurses that his union would “fully support any legal action that you feel is necessary to win your demands.” Local 340 members fully understood the importance of maintaining solidarity, having recently come off a bitter 18-month strike at Coles Express trucking that ended in a devastating defeat for the union.

Chief steward Sandy Stuart of Bangor said nurses wanted to have a say in management decisions in order to provide quality patient care. Other issues included health insurance, length of the contract, the career ladder, and whether all RNs would have to pay for the cost of union representation. Pay was also issue, but it was not main issue. Stuart told a reporter that she wouldn’t put her job on the line “for a 2 percent pay raise.”

“We are patients’ advocates,” said Cushman, the union treasurer.

“If we can’t protect ourselves, we can’t protect our patients,” said Kim Pomeroy of Bangor, an ICU nurse.

“We’re risking our homes and our families,” another nurse said.

“They say they are going to permanently replace us,” Stuart said, pointing to a big nurses-wanted advertisement the hospital leaders have been running in the BDN.

Another said they were the sole support of themselves and their families and faced the possibility of losing everything by striking. Janet Perrault of Dixmont said it came down to a question of “how we’re going to survive.” But there are positive signs, the nurses said. “The support has been unreal,” said Pomeroy, and others chimed in saying that support has come from doctors, nurses from around the state, members of other unions and especially patients.

But it is, one nurse said as she shook her head, a “stressful time for everyone.”

EMMC management assured its patients that public safety would not be at risk in the event of a strike and would continue to operate as usual. In its communications with the Governor, management said, “with some overtime and staffing adjustments, we can handle the normal census for this time of year with maintenance of quality service.” Speaking to the Bangor Daily News, EMMC administrator Thomas Zellers, said it already had 50 applicants for RN positions and wouldn’t hesitate to permanently replace striking nurses if they "abandon their patients.”

“This isn’t a threat,” said Zellers in an interview four days before the strike deadline. “It is the only choice we have to respond to those vacancies” that might be created by a strike. Striking nurses wouldn’t be fired, but they might find, if the dispute is settled, that they don’t get the same jobs back upon returning, Zellers said. “That is the risk that you take if you strike,” he said.

As the strike loomed, the phone rang constantly at strike headquarters as callers asked for updates from negotiations in Augusta, but there was little progress to report.

Trustees deny attempt to “bust” nurses’ union

According to the nurses, there wasn’t any question that the hospital was desperately trying to break their union. The pro-management Bangor Daily News noted that, “Labor is the highest cost of almost any business,” so if the union was broken “hospital’s management could, possibly, have more leeway in charting its own destiny during an era when many health care institutions are expected to be in a financial bind.” Although 1984 wasn’t turning out to be as disastrous a year for unions as 1983, the paper wrote that “memory of unsuccessful strikes both nationally and locally is still fresh in the minds of most people in the community.”

“With unions on the defensive, wouldn’t it be a good time for management to make its move?” the BDN suggested.

Unsurprisingly, the businessman who controlled the Board of Trustees — Chairman Doug Brown (President of Doug’s Shop n’ Save), Ralph E. Leonard (Chairman of H.E. Sargent Inc.), and Clifton G. Eames (President of N.H. Bragg) — denied they had any desire to go after the young nurses’ union. They claimed that if they wanted the union decertified it might have been a better strategy to offer a pay cut, but instead, the nurses were offered a pay increase. The three businessman said their approach to health care and bargaining was influenced by knowledge that sick people are the “commodity” that EMMC is in the “business” of providing care for.

“It makes it rough,” said Leonard. “If it had been my business, I would have taken a much harder line.”

“Because this is a humanitarian issue,” said Eames, “it has become very emotional, and that has prompted some observers and commentators to say we ought to be quick and ready to spend whatever it takes.” But that would be a mistake for the longterm viability of the hospital, he added.

Brown said that as trustees, it is difficult to take a firm stand because unlike their own companies, the threesome have no vested interest in the hospital. Instead they must make a moral decision for the institution over the long haul, he said.

“It was the human element that propelled us to go over the 5.3 percent limit, which from a strictly business viewpoint we shouldn’t have done,” said Brown, referring to a wage limit recommended by the hospital’s finance commission.

Four decades later, retired nurse Dottie Barron, who was chair of the nurses bargaining team in 1984, scoffed at the implication that the hospital was somehow being soft on the nurses.

“I don’t know how they could have taken a harder line than they did, but whatever,” said Barron.

In fact, at one point in negotiations, a medical center executive got so angry at her for bringing up an incident that happened at hospital on his watch that he flew across the table at Barron.

“I nearly got knocked out,” recalled Barron. “I said something truthful in a session with a mediator and two or three of the top people — our president and a couple hospital people — and he didn’t like it and he came right at me swinging.”

The federal mediator John LaPoint had to jump between the man and Barron to stop him from taking a swing at her.

“I wasn’t going to lie to [the executive]. I was there when this stuff was going on. He was in some office somewhere,” said Barron. “They’d say ‘our administrators say this’ and I’d say the administrators aren’t stupid. They’re going to tell you what you want to hear.’ I’m a very blunt person and don’t mess around with me.”

With just days to the strike deadline, doctors began anonymously speaking to the media about a strike. While some expressed fears that it would be a “disaster” and they wouldn’t be able to provide the same level of care, a number of them were very sympathetic to their nurse colleagues.

“I have problems with a society that demands the best medical care and then puts a cap on what it’s willing to pay,” said one doctor, referring to administration’s claim that nurses’ demands went beyond state health care expenditure guidelines.

“The hospital is treating nurses as a non-professional group,” said a specialist. “The nurses are angry at the way they’ve been treated. The administration has been incorrect in the way they’ve been dealing with the nurses.”

Hospital Rejects Mediator’s “Fair Share” Proposal

In the final week of negotiations, Governor Joe Brennan called both sides to Augusta to sit down with his Commissioner of Personnel David W. Bustin and federal mediator John LaPoint to hammer out a deal to prevent a strike. He had most recently intervened in a strike at Keyes Fiber (now Huhtamaki) in Waterville.

“Oh my God, it was exciting,” said Polly Campbell, who worked as an MSNA organizer on the campaign. “The Governor said I’m not going to have a nurses’ strike on my watch’ and he put us all in a state office building and said, ‘You’re not leaving until this is settled.’”

The main bone of contention was the hospital’s refusal to agree to a union security clause that would require all nurses to contribute for the cost of representation. At that time, 80 percent of the eligible nurses at EMMC were dues-paying members, but another 20 percent got the benefits of union representation without paying for it. Federal mediator John LaPoint came up with a compromise that would have given current nurses an option to remain outside the union and pay no dues; to join and pay full dues; or to pay half of the dues and only vote on matters affecting the local unit. New nurses would have the option of paying full dues or half. The nurses reluctantly agreed to the compromise.

Campbell said the the raises in the proposal were “less than we felt we could live with and distributed in such a way that the overall increase is less than the non-union employees will receive.”

“Understand that the nurses aren’t happy, but due to the public interest” were willing to accept LaPoint’s proposal, Gilmore added.

However, with one day remaining until the strike deadline, EMMC announced that it would not support LaPoint’s recommendation, even with the watered down fair share provision. In a statement, hospital officials said that “the medical center remains firm in its resolve concerning the individual freedoms of our employees. Paying all or any portion of union fees should not be a condition of employment for any nurses to work at the medical center.” Speaking to reporters, LaPoint was visibly frustrated.

“They turned it down on that one issue,” LaPoint said. “I’m obviously disappointed.” He suggested it would be difficult to head off a strike the next day.

MSNA issued a statement accusing the hospital of acting “irresponsibly” and showing “a blatant disregard for the governor’s challenge” to end the dispute.

“We say the hospital is trying once again to break up the union,” said MSNA, charging that it is using union security to “force a strike.”

“I am very angry,” said Local 1 President Anna Gilmour. “I think it is obvious that the total thing is union-busting. It is a power play with the association. They must take full responsibility for the strike.”

Nurses flooded strike headquarters with angry calls. “The nurses have been upset, but they are furious now,” said Gilmour… We were willing to take a poor economic package…What is going to happen, you are to see a much stronger strike. They have done the worst possible thing they could do. The community is really going to be angry.”

LaPoint said hospital officials had asked him why he included any form of fair share in his recommendation, knowing that they were adamantly opposed to it.

“I informed them I was a faced with a very firm position on the other side. I had no choice,” he said. “The issue is most sensitive because the long negotiations (since last May) have literally bankrupted the union.” The union “can’t compete with the hospital’s ability… to bargain endlessly,” he added.

Indeed, the nurses had lost $15,000 in personal income due to days of missed work because of bargaining. They had resorted to holding yard sales and other benefits to raise the money they needed to continue fighting. At the last minute, the Governor intervened a second time and EMMC nurses agreed to delay the strike for another two days to continue bargaining.

Meanwhile, the hospital’s allies at the Bangor Daily News went into overdrive to do damage control. In an editorial the day before the new strike deadline, the BDN’s Mark Woodward, who would later take a leave of absence to work on Senator Susan Collins’ first Senate campaign in the 1990s, accused the federal mediator of “overstep[ping] his authority” and “hurt[ing] the negotiations process” by recommending a limited fair share provision. He argued that requiring all members of the bargaining unit to pay for their union representation was akin discriminating against protected classes of people like women and African Americans.

“In an era of anti-discrimination in employment — when society is forcefully opposing job discrimination on the basis of race, religious preference, age and sex — why should the hospital be made to discriminate against prospective employees for whom union participation and forced union financial support is unacceptable?” wrote Woodward.

On the night of the Sept. 27 strike deadline, the nurses were more than ready to walk out, said Barron.

“We were ready to go off at seven that morning when the night crew went out the day before. The day crew wasn’t going in,” she said. “Yeah, it was going to happen, but Brennan put a lot of pressure on both sides to settle.”

At 1:30am on Wednesday, Sept. 27, three hours before the strike was to start, both sides reached a settlement. The strike was called off for the rank and file to consider the proposal. Under the compromise the EMMC nurses were given three options: join the union as dues-paying members, pay a “fair share” fee equal to 80 percent of union dues, or pay nothing. But a nurse paying nothing who files a grievance would pay lawyer’s fees to the union, or to private counsel.

This agreement was similar to a 1979 fair share compromise state employees reached with the state over the objections of Republican lawmakers. MSEA officials reported an increase in membership from 80 percent of those represented by the union to 90 percent following the adoption of the fair share provision.

“We are very pleased with the proposal,” said Anna Gilmore, president of MSNA Local 1. “We are convinced that the only reason the hospital capitulated was the outcry of support the nurses got from the public.”

David W. Bustin, the Governor’s Commissioner of Personnel pointed out that once the union lays out the high costs of representation in grievance proceedings many nurses would realize that it would be cheaper to belong to the union if a problem occurs with management.

Governor Brennan said he was “heartened by the settlement.”

“The agreement… is in the true spirit of compromise where neither party is totally happy, but each regards the resolution as fair and in keeping with the goal” of maintaining quality care.

However, Bustin said a lot would need to be done to repair the relationship between the RNs and management.

“I think this was as bitter a relationship between management and labor as any that I have ever seen,” said Bustin.

In the following contract in 1988, negotiations wrapped up five months early and EMMC nurses were able to win an impressive 30 percent wage, boosting maximum salaries to $40,000 a year in what a federal mediator called "a great step forward" in their professional careers. Because of their solidarity and determination, EMMC nurses were now the highest paid nurses in the state. Eventually they were also able to finally win a union security agreement where all members were required to pay their fair share for union representation, protection and benefits. MSNA negotiator Anna Gilmour said a nurse shortage also "played a role in the hospital's acceptance of the new contract."

The month after the 1984 contract was overwhelmingly ratified, Dottie Barron received the Maine State Nurses Association “Distinguished Service Award” for her leadership role in “developing a cohesive unit of professional nurses committed to raising the standards of Nursing Practice.” By that time she had served three years as director of MSNA, President of District II and chairperson of the negotiating team. She went on to serve on the MSNA executive boar for many years and chaired a committee to organize other nurses’ unions at small rural hospitals in central and Downeast Maine. She says she is proud of her work in making hospital workplaces “a little more fair,” but the fight for safe patient staffing is still a fight yet to be won.

“Nurses don’t go into nursing to learn politics and legal stuff; we go in for the care of our patients and try to make a better outcome in people’s lives,” she told an interviewer for the 2016 book Maine Nursing: Interviews and History on Caring and Competence. “For me, on a personal basis, the objective was getting a contract. I did a lot of hard work and invested a lot of time for something I believed in, and I went through a lot of stuff. I think signing that first contract for me was one of the highlights of my career. I felt like I’d fought for nursing and nursing rights. I fought for making it better for patients.”

By the 1990s, MSNA's roster included Local 982 in Mt. Desert IslandHospital, Local 10-82 at Millinocket Regional Hospital, Local 1-88 at Maine Coast Memorial Hospital in Ellsworth; Calais Regional Hospital, Local 50/50 in the Portland area, and Unit 1 in Bangor area.

Next week we will cover the struggles of nurses to organize some of these rural hospitals.