Veteran Organizer Peter Kellman Discusses the Importance of Labor History at Exhibit Reception in L/A

PHOTO: Peter Kellman speaks at a reception in Lewiston on Jan. 19.

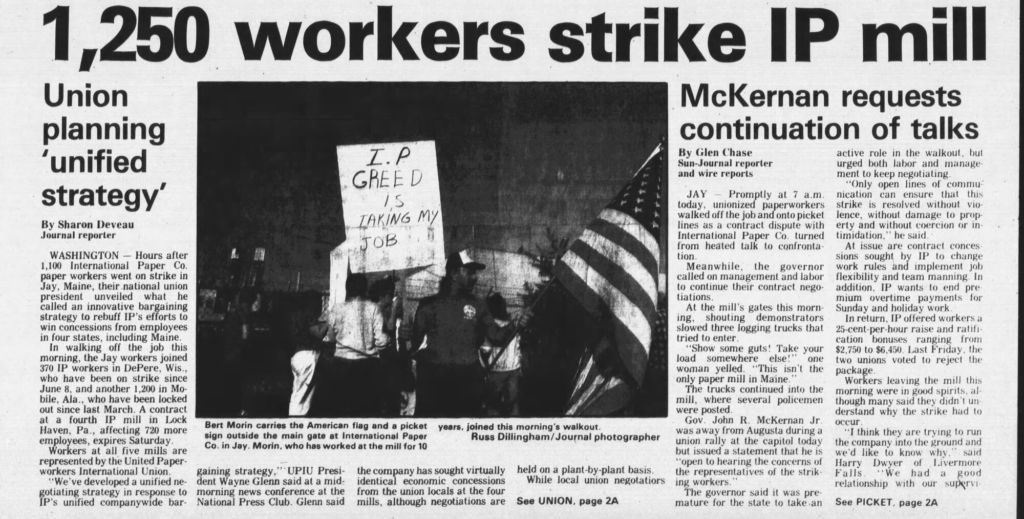

“Scabs Out! Union In!” chanted attendees at the opening reception for a new exhibitfeaturing labor artifacts and new a poster honoring the strikers from the 1987-88 International Paper Strike in Jay. Union members and activists gathered to hear speeches from Jay strikers, artist Elizabeth Jabar, Prof. Michael Hillard, author of “Shredding Paper, The Rise and Fall of Maine's Mighty Paper Industry,” and Jay strike organizer Peter Kellman on January 19 on the Lewiston/Auburn campus of the University of Southern Maine. In addition to his work in the Jay strike, Kellman was heavily involved in the Civil Rights and Anti-War Movements and is the author of the labor classic “Divided We Fall: The Story of the Paperworker's Union and the Future of Labor."

Wearing his Local 14 shirt, Kellman focused his talk on why workers need to know their history and how easily the historical thread between the past and the present can be broken.

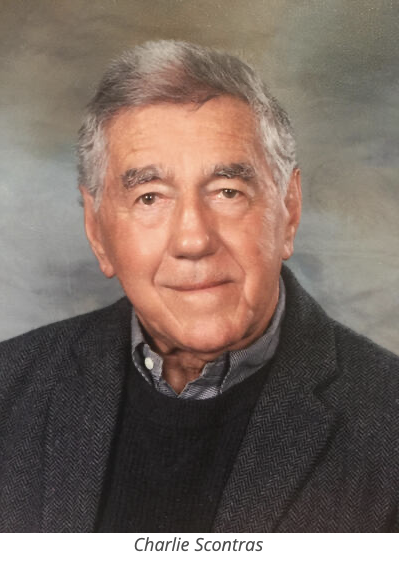

Kellman recalled the first time he met labor historian Charlie Scontras at a Maine AFL-CIO Labor Summer Institute in 1979. At the time Kellman was an officer in a shoeworkers’ union, but his heart wasn’t in labor history. He sat there half listening as Charlie went on about women textile workers in Waterville who were forced to relieve themselves behind their looms because the company didn't provide proper bathrooms. Then he banged on the table and woke Kellman up.

“He banged on the table again and he said 'Even the right to go to the bathroom is a struggle!' That’s when I became a labor historian,” said Kellman. “I felt it right here in my heart. History is important, it’s not just about reading it.”

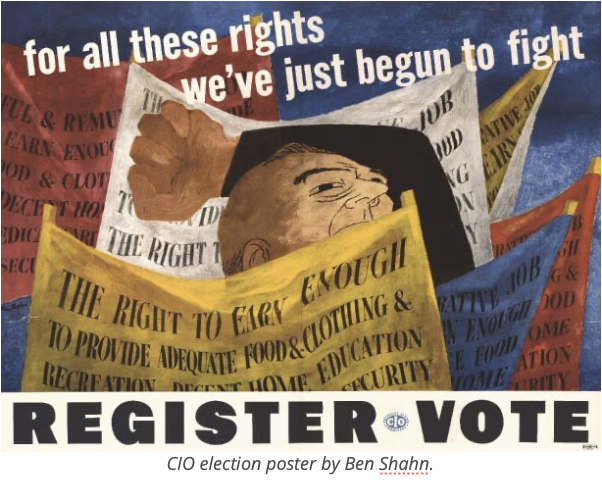

To illustrate his point, Kellman brought a 1943 pro-Roosevelt poster painted by the artist Ben Shahn for the CIO Political Action committee to accompany a blow up of the labor mural on the outside of the Local 14 union hall and Jabar’s new poster dedicated to the Jay strike for the Celebrate People's History Series.

The CIO poster, which was hung in CIO union halls across the country, called on workers to vote “For all those rights we’ve just begun to fight,” such as "The right to earn enough to provide adequate food and clothing and recreation, a decent home and education." The CIO called this the second bill of rights and put up the poster to remind people of those demands. Kellman noted that Shahn was one of the founders of the Skowhegan Art School in 1946 and taught there on many occasions.

The Skowhegan Art School also held significance to the Jay Strike as one of its students, Andrea Kantrowitz, painted the Jay labor mural depicting the many activities of the strikers. It features union members holding hands and singing “Solidarity Forever” like they did at every meeting as well as the union band and its food bank. One of its most moving scenes is of Jay workers shaking hands with other paper workers over the fence at a mill in Pine Bluff, Arkansas. Union leaders at the plant wouldn’t talk to the Jay strikers or answer their pleas for solidarity, so they approached the rank and file members themselves while they were changing shifts.

“These aren’t just posters. They’re the story of our lives,” said Kellman. “They’re the stories of our struggle.”

Kellman also discussed an example when that thread of history breaks. He remembered George Lambertson, an old time CIO man, who was the United Paperworkers International (UPIU) staff rep assigned to Local 14 during the strike. One day Lamberston was delivering a barn burner of a speech at one of the first mass union meetings of Jay workers at a gym in Livermore Falls.

“George was givin’ ‘em hell and his teeth fall out,” recalled Kellman, who also has false teeth. “So he picks them up, sticks ‘em back in and keeps right on going. They fell out again! He just takes them out, slams them on the table and keeps going. Tonight I made sure my teeth wouldn’t fall out.”

Lamberston was from Berlin, New Hampshire where he headed up a United Mine Workers paperworkers local, the CIO union that also once represented workers at the Rumford paper mill. In those days, when there was a grievance, George would walk through the mill to see the manager with his hat on straight. If the problem wasn’t remedied, he’d walk back over the factory floor with his head turned aside. Everyone would immediately stop working.

But although Lambertson could talk a blue streak about the heady days of the CIO, he didn’t know much about the struggles of paperworkers before that. When Kellman came to Jay in 1986, he would hear old timers grumble about men in town who scabbed during the strike of 1921.

“They’d say, ‘Oh that guy was a scab in ’21. We don’t talk to him,’ recalled Kellman. “That strike went on for five years in Livermore Falls.”

Kellman asked Lambertson what he knew about that paper strike sixty-five years earlier because it would be good for the workers to learn that history. Lambertson didn’t know but he asked his elderly mother back in Berlin if she knew.

“‘Oh it was really bad,” he told Kellman when he returned. “We shouldn’t talk about it.”

The thread connecting the strike of 1921 to the struggle of 1987 was broken. Kellman liked to remind the Jay strikers that the while the company controlled the mill, the workers controlled the town as they were the community. With workers on the board of selectman, they were able to raise the assessed value of the mill by $200 million. The mill provided 85 percent of the town’s tax base, so Kellman came up with the idea to use that revenue to hire all the strikers in town for $40,000 a year.

“They’d have to give back 15%. It’s not illegal. It’s not unconstitutional,” said Kellman. “But the truth is, even I thought that was a little much and I brought it to the executive board and the same thing. Everybody kind of liked it but it’s a little far out there.”

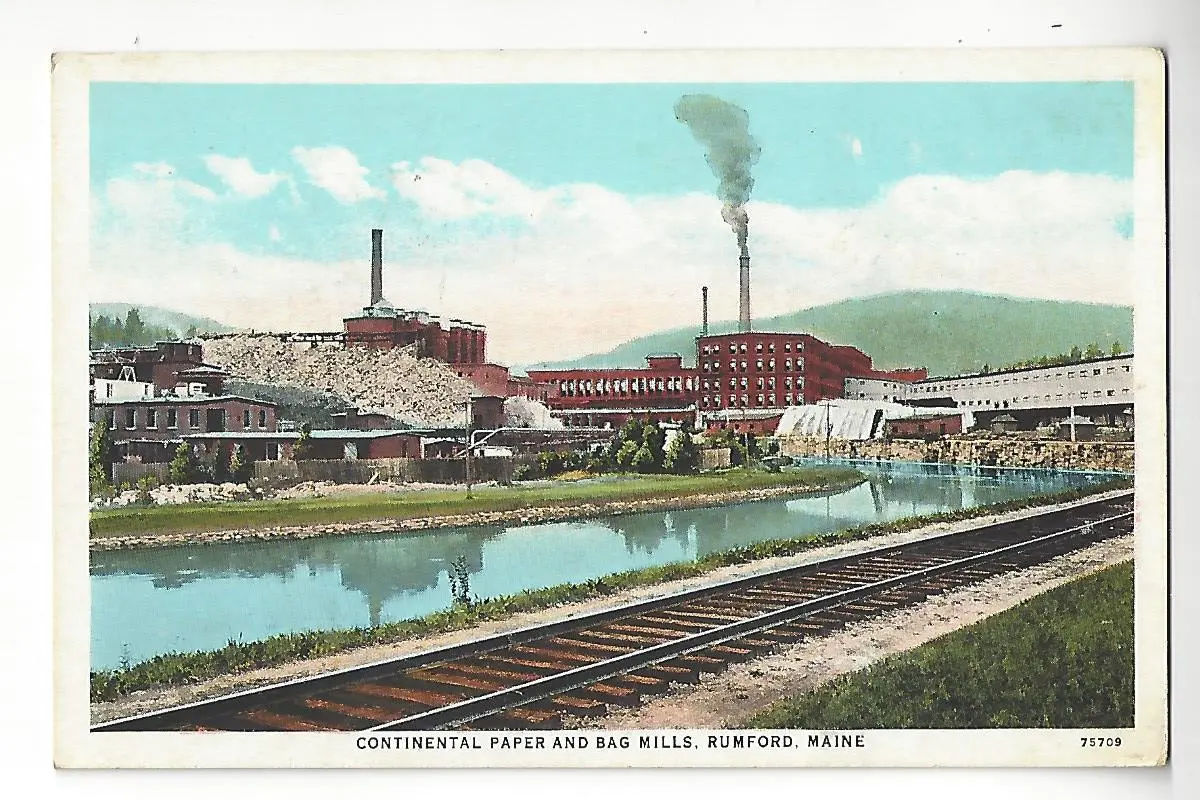

After the Jay strike was over, Kellman discovered an article in the Lewiston Daily Sundated Aug. 11, 1921 with the headline “Strikers Hold Big Mass Meeting in Rumford.” During a spirited meeting of strikers from the Continental Bag Company at the Rumford municipal building, the city clerk of Berlin, New Hampshire told the audience that striking papermakers there were struggling keep their union together.

Fortunately, the mayor of Berlin stepped in and spent $175,000 of city money to hire idled strikers to improve streets and sidewalks. Kellman speculated that if union leaders had read the article at a mass meeting during the Jay strike, someone would have inevitably made a motion to hire strikers for public works and within three days a town meeting would have appropriated the money necessary to do it.

“That’s what happens when the thread is broken,” said Kellman. “That’s why history is so important, because it’s from the history, from the past that we get the strength we need to go on.”

He said that the labor history is a story “written in blood,” from the 200 strikers killed in the Great Railroad Strike of 1877, to the 20 strikers, including eleven children, murdered by the Colorado National Guard and Colorado Fuel and Iron Company guards at Ludlow, Colorado, on April 20, 1914.

“Imagine a church without the Bible, a synagogue without the Torah, a mosque with the Quran, or the Iroquois without the creation story,” Kellman said. “It is the teachings of the stories from these great books and oral traditions that holds the congregations and tribes of our people’s together. The wisdom acquired over the ages is passed down through the stories of the past.”

“Don’t let that little thread break,” he continued. "These stories guide us into the future. They give us our values, direction and strength. Without them we are rootless, have no direction and live only in the uniformed present.”

The ceremony concluded with everyone joining hands and singing a rousing chorus of “Solidarity Forever."