"Unity in the House of Labor" — 63 Years Ago Maine AFL-CIO Became One Federation

[caption align="right"]

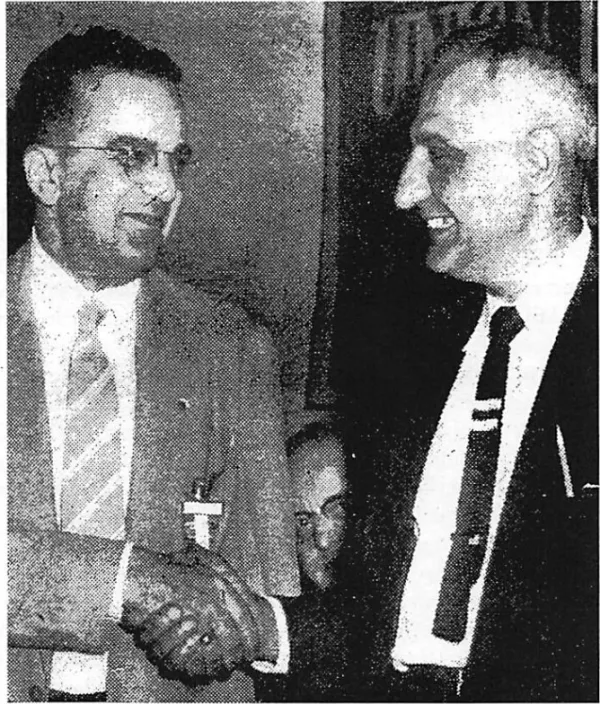

Benjamin Dorsky, President of the Maine State Federation of Labor, AFL (left) greets George Jabar, President of the Maine State Industrial Council, CIO, in anticipation of merger between the two Maine labor organizations at the Maine State Federation of Labor convention held in Old Orchard Beach in 1955. Courtesy of the Portland Press Herald.

[/caption]

63 years ago today, 60,000 Maine union members came together under one banner of the state Federated Labor Council, which later became known as the Maine AFL-CIO. The year was 1956 and Maine had just become the 19th state to approve the merger of the American Federation of Labor (AFL) and Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) after several years of tense relations between the two labor organizations.

The roots of the rivalry went back to the 1930s when the Committee for Industrial Organizations formed out of the AFL and began organizing whole workplaces along industrial lines, rather than by specific crafts. The CIO had tremendous success in organizing autoworkers, textile workers and shipbuilders, especially after President Franklin Roosevelt signed the National Labor Relations Act in 1937. However, the AFL opposed the formation of this “dual organization” on ideological and strategic grounds and voted to expel ten unions that joined the CIO, which later changed its name to the Congress of Industrial Organizations.

Maine AFL leaders didn’t like the radical militancy of this new upstart group of unions and its news organ Maine State Labor News would often run columns declaring that there was little hope for unity as long as “Communists controlled the CIO.” Nevertheless, the AFL couldn’t dispute the fact that its rival’s tactics were successful. Soon the CIO sent out a small army of organizers to organize shoe workers in Freeport, Bangor, Gardiner, Hallowell, Augusta, Norway, and Skowhegan as well as paper makers in Rumford, and shipbuilders in Bath.

One organizing drive led to the violent Lewiston-Auburn Shoe Strike of 1937, in which the companies and the state launched a full frontal assault against the workers using court injunctions, strike breakers, State Police and even the National Guard. Observing these egregious violations of workers’ rights at the time, the American Civil Liberties Union commented:

"Maine is at least one hundred years behind the times in its labor laws The civil and constitutional rights that have been interfered with are: the right to organize, the right to strike, the right to picket, the right to bail, the right to adequate representation by counsel, freedom of speech, freedom from excessive punishment, and the right to fair and impartial justice."

But the workers persisted and at the height of World War II, the Maine CIO formed its own statewide federation made up of 80,000 shipbuilders, papermakers, textile workers and others — twice the membership that the Maine AFL-CIO has today. While there were efforts to unify the AFL and CIO in the 1940s, they couldn’t come to an agreement on key issues like stopping the rampant raiding of each others’ unions. However, after a Republican-controlled Congress passed the detestable 1947 Taft-Hartley Act, which seriously weakened collective bargaining rights and allowed for “right to work laws,” the CIO and the AFL knew that they had to band together or they would both be crushed.

Back in Maine, the AFL and CIO worked together to defeat a series of initiatives designed to weaken workers’ rights. And the unions also began supporting each other in their collective struggles, whether it was AFL Truck drivers and Coca-Cola warehouse workers in South Portland and Sanford in 1948 or Portland Newspaper Guild members of the CIO striking for fair contracts in the early 1950s.

It was also the height of the McCarthy-era and the CIO earned points with the more conservative AFL by purging Communists from its ranks. Finally, a no-raiding agreement was struck in 1953 and the two national organizations agreed to support both the craft and industrial union organizing models, paving the way for an ultimate merger in December, 1955. That was also the year that Maine union members helped elect Democratic Governor Edmund Muskie, who pledged to support collective rights for workers, to sign a minimum wage law and create a state labor relations board.

Governor Muskie was in attendance on that November day in 1956 when the final merger was approved at the joint convention in Lewiston. Longtime Maine State Federation of Labor President Benjamin Dorksy, a member of the Movie Operators Union in Bangor, was elected to lead the new federation.

Speaking before the crowd of delegates, AFL-CIO Regional 1 Director Hugh Thompson called the merger “the reunion of a family,” as he outlined a plan to attract new industries to New England. Thompson’s proposal called for the region’s governors to establish tripartite boards with representation from labor, industry and the public to focus on bringing “legitimate industries to the area.” Thompson told the crowd that governors “must recognize that labor has much more to contribute than those sitting on some of the present councils who are usurping the power of the state and bringing in sweat shops to the area.”

Speakers addressed the decline of the state’s once mighty textile industry as mills were facing stiff competition from foreign imports and local jobs were being outsourced to the non-union South. TWUA President William Pollock told the Maine convention that some state industrial development commissions were attempting to fill textile mills “abandoned by financial manipulators who abandoned the communities that made them rich” with $1 an hour industries without unions.

Nevertheless, there was also a potent feeling of solidarity and optimism as the two former rival organizations had finally brought unity to the “House of Labor.” Unfortunately they were unsuccessful in stemming the tide of deindustrialization and the offshoring of jobs. In the years since then, union membership has declined significantly due to companies shipping jobs overseas and a relentless business-led attack on workers’ rights. But in 2020, the labor movement has more energy than it has had in decades as workers across the country are rising up to demand their fair share of the wealth they create. There is an amazing opportunity to build a better world for all working people if workers just forge ahead and seize it.

Source: Charles Scontras' "Unity in the House of Labor: Maine AFL-CIO Merger, 1956" (Bureau of Labor Education, 2006).