"Right to Work" — A 75-Year Class War Against Maine Workers

As long as workers have been forming unions in Maine, anti-labor politicians, judges and the business interests that support them have rigged the system against workers. In the first half of the 19th century, American workers who went on strike were often charged or indicted for criminal conspiracy in restraint of trade. In 1840, the Belfast Republican Journal criticized noted the double standard when it came to anti-labor sentiment:

"Banks and manners of corporations enter into combination for self protection and nothing is done about it, but if two shoemakers agree together that they will not labor under (certain) prices, they are liable to punishment by law. This may seem incredible, but is positively so.”

In 1880, the Maine Legislature sided with employers when it passed a conspiracy law that effectively outlawed strikes. The law was passed in reaction to massive nationwide rail road strikes that were put down violently by militias and federal troops. The Maine Legislature also defeated union-endorsed bills that would have prohibited employers from blacklisting union workers and forcing them to sign "yellow dog" contracts pledging not to join a union as a condition of their employment.

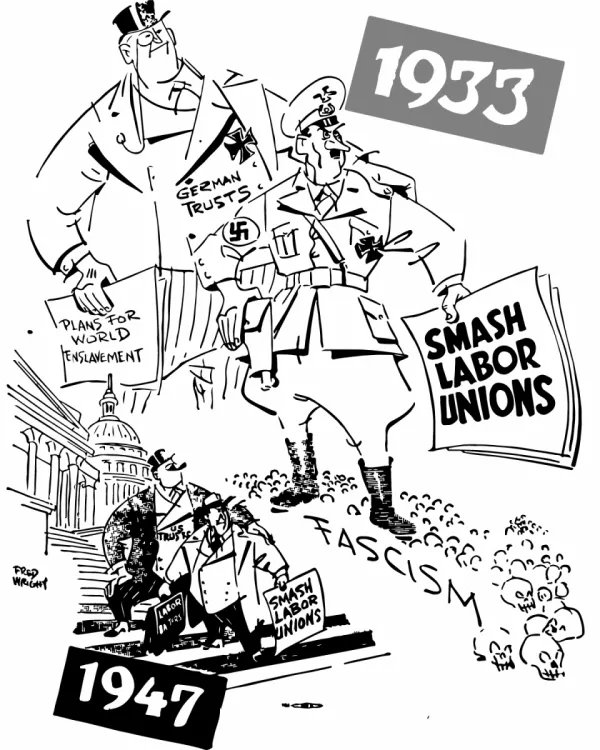

It wasn’t until President Franklin Delano Roosevelt and New Deal Democrats established the right of workers to collectively bargain in the 1930s that workers got a fair shake when it came to collective action. The National Labor Relations Act became known as the “Magna Carta” of the American Labor movement, but business interests vowed to gut it as soon as they could muster enough votes in Congress.

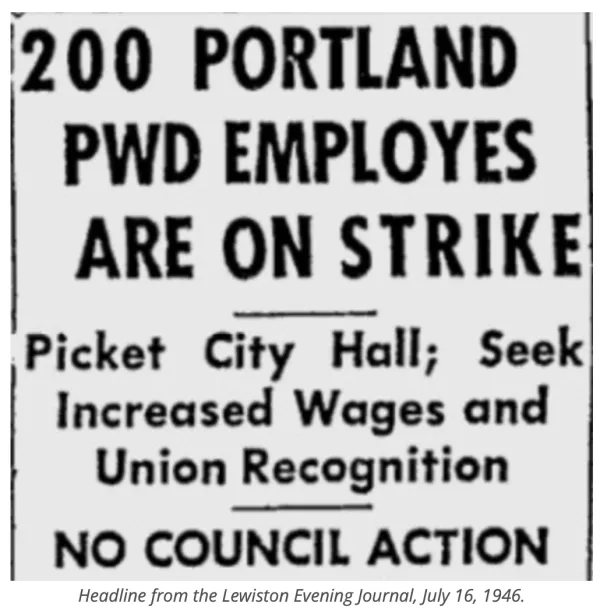

A Portland City Manager & The "Slave Labor Bill"

In the aftermath of World War II between 1945 and 1946, a massive strike wave erupted across the nation as more than five million workers spanning several industries walked off the job to demand fair wages and better treatment. On June 16, 1946 in Portland, the first major public employees strike in Maine kicked off as Portland Public Works employees with the recently organized Portland Local 946 of the State, County, and Municipal Employees (AFSCME) walked off the job after City Manager James E. Barlow and the Portland City Council refused to recognize their union.

After a general strike was called, 200 workers, including union truck drivers, machine operators, blacksmiths, stone quarry and asphalt plant workers, mechanics, laborers, machinists, longshoremen, barbers, painters, carpenters, electricians, plumbers, and steamfitters joined the general strike in a powerful show of solidarity. Barlow, who was already well known as a notorious anti-labor zealot, cited the general strike in his drive to pass union busting legislation, including a ban on such sympathy strikes.

After Republicans took over Congress during the 1946 midterm elections, a coalition of Republican lawmakers and anti-labor Southern Democrats did just that and more. The 1947 Taft-Hartley Act, dubbed the “Slave Labor Act” by its opponents, prohibited sympathy strikes, secondary boycotts and secondary picketing. It also permitted states to ban the closed union shop by enacting “right-to-work” legislation. Supporters of these right-to-work bills sought to weaken the collective power of workers by banning union contracts that require workers in the bargaining unit to pay dues for the cost of collective bargaining.

Maine’s two Republican Senators, Margaret Chase Smith and Wallace White, voted for Taft Hartley. Notably, Smith opposed efforts to make Maine a right to work state, which is one of the reasons the Maine State Federation of Labor made the controversial decision to endorse her in the 1954 election, much to the anger of its more progressive members.

Following passage of Taft Hartley, City Manager Barlow spearheaded a citizen initiative in 1948 to make Maine a right-to-work state. According to Maine labor historian Charlie Scontras, the so-called “Barlow bill” would have banned the closed shop, the union shop, and maintenance of membership contracts, and would make illegal secondary strikes and boycotts, sympathy strikes and jurisdictional strikes, the dues check-off system, and even picketing around agricultural businesses. Another competing ballot question authored by Republican Rep. Foster F. Tabb of Gardiner outlawed the closed shop, but not the union shop.

In the summer of 1948, Barlow and his business-funded “Maine Committee to Protect the Right to Work” barraged Mainers with misleading ads claiming that the measure was needed to protect men from being fired for not joining unions or thrown out of work due to strikes. However, Mainers saw through the anti-labor propaganda and crushed both the Barlow Bill and the Tabb Bill referendums in a landslide by two-to-one margins in the election on September 13, 1948.

The unpopularity of right-to-work laws with Maine voters didn’t stop anti-labor organizations from continuing to spread anti-union propaganda and influencing legislators to pass right-to-work bills. And they haven't let up since. As Scontras noted, while the arguments for and against “right-to-work” haven’t change much, the political winds have.

In the 1960s, prominent Maine Republicans including Governor John Reed, Sen. Margaret Chase Smith and Congressman Stanley Tupper all opposed making Maine a right-to-work state. Unfortunately, much has changed in Maine politics since then. In 2021, just one Republican Senator, Sen. Scott Cyrway (R-Benton), a former Kennebec County deputy patrol sheriff and corrections officer, and one State Representative, Rep. Tim Theriault (R-China), a former union welder, voted against right-to-work legislation.

As we approach another midterm election it is worth researching candidates records on key labor issues including how they've voted on so called Right to Work for less bills. Check out our 2022 Working Families Legislative Scorecard for more information.