The History of Union Organizing at Bath Iron Works

PHOTO: lAMAW Local S6 member Doug Hall on strike on his birthday in 2020.

Whenever there’s a picket line in Maine, chances are you’ll see Machinists Local S6 member Doug Hall right there holding a sign. A stalwart union man since the 1980s, Hall was elected as a Local S6 shop steward in 1994 and elected to the grievance committee in 1998, where he has served for seven terms. He's also served as a chief steward and on the union’s negotiating committee during the 2020 strike.

Originally from Farmington, Hall said he didn’t grow up in a union household, but he developed a strong sense of class consciousness as a young man. After graduating high school in 1986, he went to work at the Forster toothpick factory in Strong where he and his cousin were members of United Paperworkers International Union Local 14.

Despite the town’s name, it wasn’t a particularly strong union, recalls Hall. But when thousands of Local 14 members walked off the job during the International Paper Strike of 1987 Hall became more radicalized. His uncle was among the strikers, so instead of scabbing like some of his former classmates, Hall joined his family on the picket line. A year later in 1988, he went to work at Bath Iron Works with a firm understanding of what it means to have solidarity for one’s union brothers and sisters.

“I went from making toothpicks to war ships,” said Hall.

It was there that he became a part of a long, militant union tradition going back to the 1930s when shipbuilders with the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) began organizing for better wages and workplace safety. With so many younger members coming to work at the shipyard in the past few years, Hall is passionate about teaching them about their union’s proud history and instilling in them the spirit of CIO.

Formed in 1935, the CIO was originally called the Committee of Industrial Organizations that worked within the American Federation of Labor. Led by charismatic United Mine Workers leader John L. Lewis, It changed its name to the Congress of Industrial Organizations after it broke away from the AFL due to a fundamental disagreement on organizing strategy and became a separate federation of unions in 1938.

Unlike AFL unions, CIO affiliate unions organized all workers — Black, white, men, women, skilled and so-called “unskilled” — into factory wide “wall-to-wall unions.” AFL unions only organized the highest paid skilled craft workers and typically excluded women and Black workers. The International Brotherhood of Boilermakers, then the largest shipbuilding union, refused to admit Black workers and instead placed them in “auxiliary” unions that put them in a “subservient position compared to the white unions.” Thanks to CIO organizing Black union membership grew from 100,000 to half a million from 1935 to 1940.

“The CIO’s philosophy was always ‘we’re all equal, it doesn’t matter.’ We were on the cutting edge of fighting racism during the CIO days of the 1930s and 40s,” said Hall. “I think it’s something we need to get back to teaching members. Human rights should always tie into being in a union.”

CIO supporters argued that while the craft union model may work in other workplaces, dividing workers in a single factory into several different crafts with their own agendas weakened workers’ collective bargaining power and left the lowest paid workers without union representation.

“As far as shipbuilding, we are the last industrial CIO union that represents wall-to-wall members. All of our production workers are organized under one umbrella, from maintenance and custodians to the skilled trades,” says Hall “Our philosophy was to organize the entire workplace because that’s the only way to beat the company. When we’re all in it together we have more power.”

Other shipyards have what are known as Metal Trades Councils, made up of several separate craft unions, but Local S6 includes all of the production workers. Hall argues that Local 6’s industrial union model makes it more militant because the company is less able to pit unions against each other.

“The company tries to drive wedges between workers wherever they can,” says Hall. “If they can divide workers by giving out raises to some and not others, or treating trades differently they will. Under the CIO model, it’s harder for them to do that."

The cornerstone to the Local S6 contract is seniority. Rather than simply laying off workers when work is slow in a particular department, there’s a provision in the contract that allows them to be loaned to other trades or take recalls into other departments based on seniority.

“That’s a lot harder when you get into metal trades council because they’re two separate entities,” Hall said. “If I’m a tin knocker in the sheetmetal union my primary concern are tin knockers because you’re elected by those people. Industrial unions are more radical.”

When Bath shipbuilders began organizing with the CIO in the 1930s, CIO workers were in the midst of massive nationwide struggles that culminated in collective bargaining agreements at US Steel and General Motors, following a dramatic forty four-day sit-down strike. From Detroit and Pittsburgh to the tiny village of Bath, Maine, the momentum was unstoppable.

Organizing the First Union at Bath Ironworks

This week marks the 90th anniversary of when workers at Bath Iron Works in Bath joined shipbuilders from Quincy, MA; Camden, NJ; Chester, PA; Wilmington DE and New London, CT to found the Industrial Union of Marine and Shipbuilding Workers of America (IUMSWA), CIO in Camden, New Jersey on October 3, 1933. Their goal was to unite all shipyard workers — Black and white, men and women — regardless of their trade/craft or level of skill. As their founding document stated:

"Recognizing that craft unionism, as practiced in the past, has been proven to be both ineffective and dangerous to the interests of the workers, the Industrial Union of Marine and Shipbuilding Workers of America advocates and practices the program and tactics of militant industrial unionism, based on the principle of One Industry-One Union. [IUMSWA] calls for the united front of all workers in the industry, regardless of creed, color, nationality, religion, sex or political affiliation. It bases itself upon the principle of rank and file control, unrestricted trade union democracy, and at all times an aggressive struggle for an ever higher standard of living.”

Union shipbuilders in Bath argued that they were the lowest paid workers in the industry and compared their working conditions to a “sweatshop.” In the IUMSWA newspaper, The Shipyard Worker, workers complained that there was "no such thing as a work week here as the whistle and calendar have been discarded [and] pay checks are based on whatever the management sees fit to pay.” The paper complained of blatant “favoritism” in the yard in terms of who got a raise or were promoted.

While IUMSWA Local 4 at BIW was issued a charter on Sept. 29, 1934, members didn’t have a collective bargaining agreement and its charter was suspended two years later due to weak leadership. According to The Shipyard Workers, Local 4 couldn’t find a hall anywhere in Bath to hold their meetings because "this town can't afford to do anything that [BIW President] Mr. [William S.] Newell doesn't approve of.” The company was virulently anti-union and fired shipbuilders for organizing.

Because they didn’t have a contract with a union security clause, IUMSWA stewards like welder Arthur Lebell had to find other employees at lunch breaks and outside of work to collect dues from them. The company vigilantly watched pro-union workers and when it came time for lay offs in 1935, Lebell was among the shipbuilders who were dismissed for union activity.

“And when I got laid off, my immediate supervisor told me that there must be a reason for you to get laid off,” recalled Lebell in a 1973 interview. “‘Arthur,’ he said, ‘you're doing good work.’ He said, ‘A union is alright to belong to, but not to have too much to say about.’ And it was obvious that I got laid off for union activity.”

Lebell went to work at the Four River Shipyard in Quincy, Massachusetts for a year and a half before work picked up again at BIW and he was hired back.

As labor historian Charlie Scontras wrote in his book Labor in Maine: Building the Arsenal for Democracy shipbuilders resumed organizing in 1938 after being inspired by passage of the National Labor Relations Act, which made it US policy to encourage collective bargaining by protecting workers’ freedom of association. IUMSWA’s charter was restored that July with a membership of 500 shipbuilders.

What followed, writes Scontras, was “two decades of bitter rivalry” between IUMSWA, CIO and the more conservative American Federation of Labor (AFL). When the Metal Trades Council, AFL held a rally in Bath, CIO sympathizers were reportedly driven from the hall because they had accused the AFL of collaborating with management to defeat the industrial union.

The CIO claimed that the International Brotherhood of Boilermakers, an AFL union, had sent invitations to the rally with the names of each employee, including supervisors and foremen, and their payroll numbers — information they could have only obtained from management.

“How did the A.F.L. get the names and clock numbers of every worker in the Bath Iron Works?” IUMSWA demanded to know.

IUMSWA claimed that the company sent out notices stating that it "was not committed in favor of any labor organization” to avoid being charged with an unfair labor practice with NLRB. However, according to The Shipyard Worker, an AFL representative admitted the company’s bias towards the AFL in stating that former Democratic Governor Louis J. Brann had introduced him to a company official.

In the first election for union recognition on December 21, 1938, the union was narrowly defeated as 861 workers voted against having a union, 819 voted for IUMSWA and 294 voted to affiliate with the Boilermakers. According to Arthur Lebell, who was then IUMSWA Local 4 President, the company defeated the union by posting a notice granting a five percent increase in pay and the first night shift premium pay at the yard just 24 hours before the secret ballot election. The workers who were “sitting on the fence” decided to vote against the union due to the last minute move.

Lebell said that while there had initially been strong pro-union sentiment at the shipyard, support for the CIO union weakened after about a thousand striking CIO shoe workers defied a court injunction on April 21, 1937 by peacefully marching across a bridge linking Lewiston and Auburn. Mayhem ensued as police violently attacked the crowd of mostly Franco-American women workers. Republican Governor Lewis Barrows called in the Maine Army National Guard to "restore order" following the violence.

The following month, a judge found CIO organizer Powers Hapgood and seven other strike leaders in contempt of the injunction and sentenced them to six-month prison terms. The decision was later overturned by the Supreme Judicial Court and Hapgood was released. But on June 29, 1937 CIO workers called off the strike for lack of resources and support.

“[Shipbuilders] knew that they couldn't do anything alone," said Lebell, "but prior to that there had been a shoe strike in the Lewiston-Auburn area that was pretty tragic in that it was unsuccessful and this was because the employers wouldn't abide by the National Labor Relations Act at the time. They had said it was unconstitutional and the phantom of this strike kind of frightened a lot of people who came from that area.”

In a report about the strike titled “The Fascist Boot Fits Maine," the American Civil Liberties Union wrote that "Maine is at least one hundred years behind the times in its labor laws. . . . The civil and constitutional rights that have been interfered with are: the right to organize, the right to strike, the right to picket, the right to bail, the right of adequate representation by counsel, freedom of speech, freedom from excessive punishment and the right to fair and impartial Justice."

Front page of the Portland Press Herald, April 23, 1937

In spite of a hostile business class and an anti-labor state government, the CIO was incredibly successful in unionizing Maine industries in the late 1930s and early 1940s.

As Scontras writes, by 1942, the Textile Workers Union of America (TWUA), CIO had won bargaining rights for 17,500 textile workers in 90 percent of the cotton industry in Maine, including the Pepperell Manufacturing Company (Biddeford), York Manufacturing Company (Saco), Saco-Lowell Machine Shop (Saco), Continental Mill (Lewiston), Androscoggin Mill (Lewiston), Hill Manufacturing Company (Lewiston), Bates Manufacturing Company (Lewiston), Lewiston Bleachery (Lewiston), and the Edwards Manufacturing Company (Augusta). In 1939, Bath Iron Works shipbuilders at the rapidly growing South Portland shipyard had organized with IUMSWA, CIO.

The BIW shipbuilders in Bath would prove to be a tougher nut to crack. But as the US dramatically ramped up production of warships to build President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s "The Arsenal of Democracy,” the vast majority of shipbuilders wanted to join a union. But the workers were deeply divided about about whether they wanted to join a conservative craft union or the militant CIO.

Maine Workers & the March to World War II

In the past several weeks, we’ve covered the first successful union drive at Bath Iron Works and the wildcat strikes that followed at the height of World War II. Initially we were going to cover the victory of workers in the South Portland shipyards in organizing with the CIO this week. However, with today being the 82nd anniversary of the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor we felt it’s an appropriate time to discuss the lead up to the war and the role of Maine workers in building the massive arsenal necessary to defend democracy and freedom throughout the world.

In the lead up to World World II, Mainers were divided about entering the war. In fact, even as Hitler’s army invaded Poland and Britain declared war on Germany in 1939, Maine’s entire Republican congressional delegation — Senators Wallace H. White and Frederick Hale and Representatives Oliver (South Portland), Clyde Smith (Skowhegan) and Ralph Owen Brewster (Dexter) — opposed getting entangled in another war in Europe. Gradually, over the next two years, all of them except Oliver would moderate their positions and unite in support of the war effort.

As Maine labor historian Charlie Scontras wrote in his book “Labor in Maine: Building the Arsenal for Democracy: 1939-1952,” pacifist groups like the League of Peace and Freedom chapters in Portland and Bangor and isolationists in the 800,000-member America First Committee organized against military intervention in Europe.

In 1940, President Franklin Roosevelt campaigned on keeping the US out of the war, stating famously, ”I have said this before, but I shall say it again and again and again; your boys are not going to be sent into any foreign wars." However, he strongly supported Britain in its fight against the Nazis and believed that the US should serve as a "great arsenal of democracy.” It was clear that Hitler was not going to give up his fanatical ambition to conquer Europe for the benefit of the so-called Aryan race, except by force.

As Francis Rexford Cooley writes, although Maine was a majority Republican state, they were not necessarily isolationists. In 1939, Rep. Ralph Owen Brewster found support for amending the nation's neutrality laws after polling 8,000 Maine Republicans. Shortly after, he voted to lift an arms embargo with Britain and France and prohibit trade with “belligerent” countries like Germany.

Then in July of 1940, after the German Navy destroyed eleven British destroyers over a ten-day period President Roosevelt responded by exchanging 50 destroyers for 99-year leases on British bases in Newfoundland and the Caribbean. Maine State Labor News, the news organ of the Maine State Federation of Labor, AFL, supported the decision, but the Bath Daily Times complained that the government wasn’t moving fast enough on approving contracts to build new warships.

Congressman Oliver, on the other hand, blasted FDR’s unilateral decision, stating that the President was moving toward a "military dictatorship in America.” He closely aligned with the isolationist aviator Charles Lindbergh and the America First Committee and sent reprints of Lindbergh’s testimony against the Lend-Lease Act to constituents. Oliver received withering criticism from voters and the press for his ties to the controversial Lindbergh and America First, which attracted many prominent anti-semitic and fascist sympathizers like automobile baron Henry Ford.

In September 1940, Congress enacted the first peace time draft in US history and Japan signed a mutual-assistance pact with Germany and Italy. The following March of 1941, it also passed the Lend-Lease Act to "lend-lease or dispose of arms" and other supplies needed by any country whose security was vital to the defense of the US. The act resulted in billions of dollars in arms and munitions going to Britain on the Western Front and the Soviet Union on the Eastern Front.

The America First Committee eventually opened an office in Portland in Sept. 1941, but by then the wheels of war set in motion. The rest of the congressional delegation except Oliver coalesced behind Great Britain. Once the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, the US entering the war was a forgone conclusion. Robert Hale crushed Oliver in a GOP primary in June, 1942, delivering a decisive defeat to isolationism in Maine.

Even before Pearl Harbor, there were also strong economic incentives for Maine’s congressional delegation to support the war. Previously a major part of BIW's business was building yachts, but demand for them declined precipitously during the Great Depression, causing the workforce to shrink. Thanks to a record $3.9 billion defense appropriation from Congress, BIW was awarded eleven destroyer contracts and the Portsmouth yard received six new submarine contracts in September 1940. To meet the demand for warships, BIW also joined a syndicate of other shipyards to form the New England Shipbuilding Corporation and began construction on the new Todd-Bath shipyard in South Portland, right in the heart of Rep. Oliver's district, in August, 1941.

Additionally, Congress provided $5 million for construction of an Air Corps base in Bangor to protect America’s eastern-most border from German attacks. The Maine State Labor News enthusiastically reported in December, 1940 that the project amounted to the “biggest building boom ever known by Bangor Building Trades mechanics.”The war economy promised huge gains for both businessman and Maine workers. The wartime boom pulled tens of thousands of Mainers out of the Depression as unemployment plunged from 17.2 percent in 1939 to less than 2 percent in 1945.

“For the first time in American history an intensive effort will be made to revive every ‘ghost town’ where factories have been abandoned and workers left stranded,” announced Sidney Hillman, head of the labor division of the National Defense Advisory Commission in Maine State Labor News in November, 1940.

From the textile factories of Lewiston to the farms of Aroostook County, the shipyards, paper mills and Downeast fish canneries, Mainers set to work around the clock to support the war effort. Union leaders patriotically declared that their rank and file members were prepared to “cooperate to the utmost in the national defense program."

“Labor knows that it is the first to be trampled under the march of dictatorship,” announced the union representatives on the Labor Policy Advisory Committee of the National Defense Advisory Commission following the attack on Pear Harbor. “Labor knows that if workers are to remain free men and keep their free choices, democracy — as a living faith, as a living reality — must be equipped to meet the threat of totalitarianism within and without. Labor has been — and is — cooperating wholeheartedly throughout the entire defense effort.”

Maine Workers Mobilize for Wartime Production

In our latest segment on the role of Maine workers in the war effort during World War II, we borrow liberally from the late labor historian Charlie Scontras’ book “Labor in Maine: Building the Arsenal of Democracy and Resisting Reaction at Home, 1939-1952.”

A year and half before the US officially entered World War II, Maine Governor Lewis Barrows was already taking steps to prevent espionage and sabotage of critical installations in the state. The Governor ordered guards on 24-hour watch over Maine’s 32 armories, arsenals and military stores. Soldiers in Maine’s National Guard immediately began training for “mock wars” and fifteen privately organized defense units with approximately 1,100 men were drilling weekly by the fall of 1941.

Barrows also issued a proclamation requiring foreign nationals to register with the state and by July of 1940, 20,000 New Mainers had complied with the order. The state went so far as to confiscate the cameras, guns and short wave radios of Italian immigrants and didn’t return their possessions until 1944.

After the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, Maine went into full-wartime production mode. Shortly after the attack, John R. Newell, Assistant Manager of the Bath Iron Works Corporation, expressed fear that the shipbuilding city of Bath could be a target for enemy bombings like the German air raids of Coventry, England a year earlier.

“If Bath is bombed—and it may come tonight or tomorrow night—there will not be just two or three bombs or two or three fires, for I believe it will be an effort to make Bath another Coventry,” he told the Lewiston Daily Sun.

The Maine National Guard was ordered to “remain on alert, the State Police were put on standby for emergency calls and Deputy Sheriffs were required to be subject to 24-hour duty if needed. The same month, the Civilian Defense Commission announced that a network was set up to monitor forest-stream areas for saboteurs targeting the hydro electric dams that powered Maine’s war industries. In February, 1942, an active mine field was placed at the entrance of Portsmouth Harbor to protect Kittery Naval Shipyard from German submarines. The Coast Artillery positioned its mobile artillery to protect the Portland Harbor.

In a simulation of dive-bombing attacks, fifteen Navy planes “bombed” Portland Harbor, while the city’s Portland Public Works Department distributed sand to residents for extinguishing incendiary bombs. Air raid drills were frequently practiced in Portland and in other towns by ringing church bells and turning off street lights until air raid sirens were secured.

Citizen groups were also organized to monitor various parts of the state. The American Legion had more than 500 air warning observation posts with more than 10,000 watchers who were under the direct supervision of the Army. The states Forestry Department enlisted its wardens and 20,000 Sportsmen's Club members to ensure the protection of the state’s natural resources like timber. The State's Fish-Game Commissioner, George J. Stoble, promised a "warm reception" to anyone who planned to sabotage the forest lands of the state.

10,000 local fishermen were recruited to be the “eyes and ears” of the coastline by watching for any suspicious crafts. Boaters in. Portland formed a a Coast Guard auxiliary flotilla to patrol Casco Bay. Mainers were told to be on the look out for “fifth columnists” who secretly aided the enemy. The State Police investigated immigrants building warships at Bath Iron Works and required all of the workers be finger printed.

Maine’s Health Department made efforts to get all Mainers vaccinated for diphtheria, typhoid fever, and smallpox in case the state’s water supplies were damaged in an enemy attack. Local fire departments were trained to handle potential fire bombings.

Maine Workers Mobilize for Wartime Economy

Even before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941, Maine’s wartime economy was booming as Mainers worked around the clock to fulfill orders for Navy warships, ammunition, gun mounts, airplane parts, propellers, gas mask bags, bullet-making machines, submarine components, toothpicks, smokeless powder, paperboard containers for shells, paper parachutes, blood plasma kits, food and much more.

"Virtually every industry in Maine today is working wholly or partially on so-called war orders or is engaged in making goods necessary to the national comfort or morale,” remarked State Safety Director Arthur F. Minchin on Sept. 8, 1941.

Unionized workers in the state's textile hubs were busy making fatigues, parachutes, blankets tents and all types of clothing and accessories for the soldiers on the front lines in Europe. Shoe factories produced shoes for nurses and refugees, Alaskan snowshoes, laced leather boots and harnesses while cannery workers produced Turshonka, a canned stewed pork for Soviet troops.

In 1943, the New England Shipbuilding Corporation, which included the Todd-Bath Iron Shipbuilding Corporation and the South Portland Shipbuilding Corporation in South Portland, Bath Iron Works in Bath and the US Navy Yard in Kittery employed nearly 60,000 workers, including 8,526 women to help build the Navy’s war fleet. By 1945, Maine shipbuilders had built 234 Liberty Ships, sixty-four destroyers and seventy-one submarines. Even smaller shipyards in Maine in Mount Desert Island, Camden-Rockland and Boothbay were kept busy building minesweepers, salvage vessels, submarine net tenders, picket boats, barges, transports, and other vessels.

The wartime boom pulled thousands of Mainers out of the Depression as unemployment plunged from 17.2 percent in 1939 to less than 2 percent in 1945. The state Health and Welfare Commissioner reported that "scarcely an employable person remains on Maine's dwindling emergency aid rolls and virtually all employables have been weeded off direct relief.”

The wartime boom of high-paying defense jobs in the shipyards created massive labor shortages in lower paying industries like farming, canning, textiles and shoe factories. As a result, schools in Aroostook County had to delay the start of the school year to allow students to harvest all of the food. The number of minors issued work permits nearly tripled from 1940 to 1942 with 6,520 youths employed. Even teachers were asked to join the harvest alongside their students during their summer breaks.

Because so many textile workers left the mills of Lewiston to work in the South Portland yards, it was said that "Lewiston mills help built the shipyards.” Hundreds of Jamaican laborers recruited by the War Food Administration to harvest canning crops and potatoes in Maine were also hired to fill positions at Southern Maine foundries.

People with disabilities were also encouraged to join the workforce to support the war effort. One report described how fifty invalid women in the Penobscot region were working from home, making mesh bags from twine for the Navy.

"Cripples [were) no longer barred from war worker ranks. The lame, the halt and the blind, today loomed as a saving grace as employment agencies throughout this area sought frantically to fill unprecedented demands for able bodied workers in the accelerated war effort,” reported the Portland Evening Express in April, 1942. “Men and women, normally barred from competition for jobs because of amputated arms, hands or legs, failing sight, shriveled limbs, faltering hearts, and numerous other physical defects are beginning to be recognized as important cogs in the replacement of workers in civilian employment.”

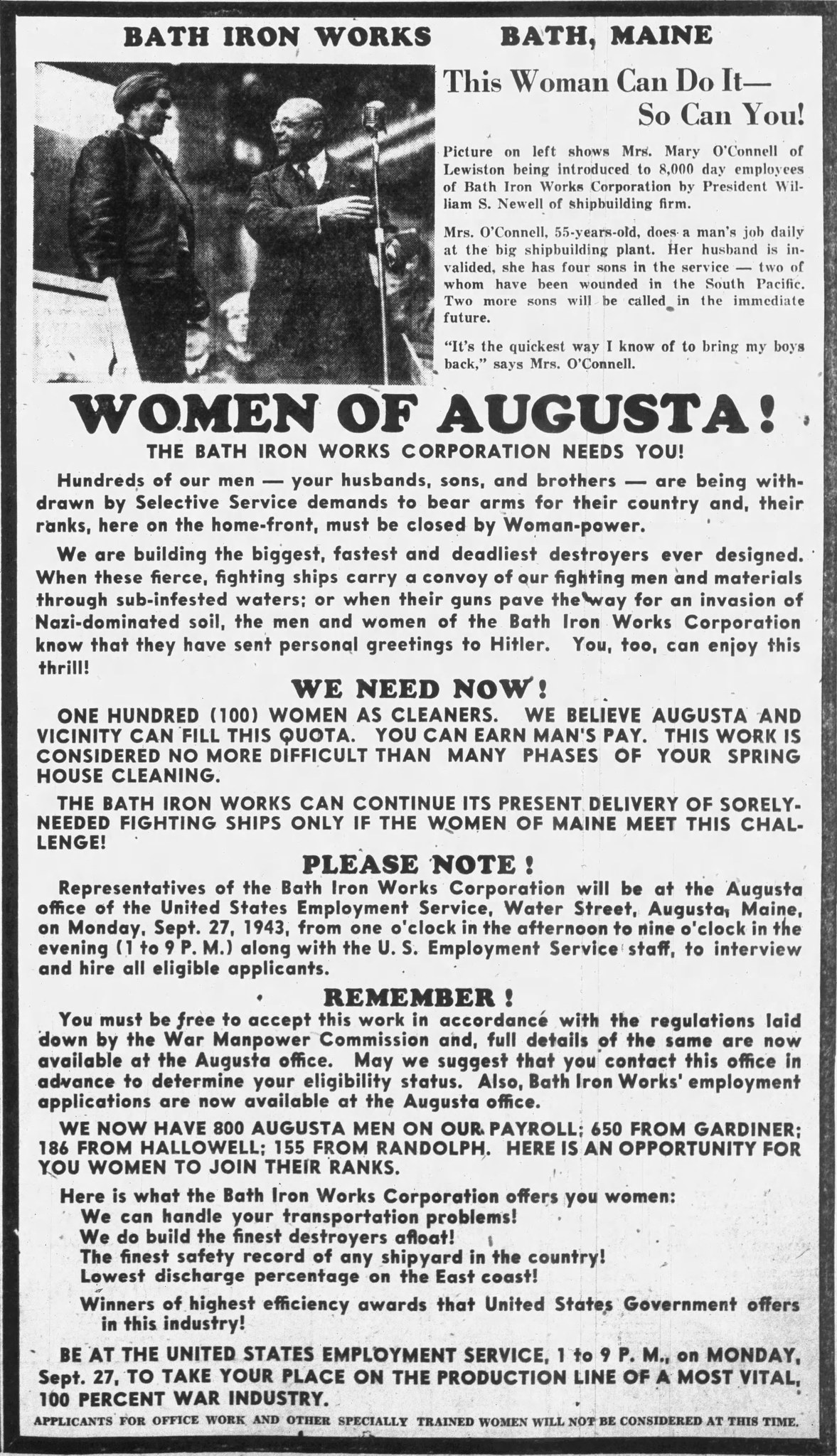

BIW recruitment ad targeting women workers. Circa 1940s.

Women were critical to building up the defense industry and Bath Iron Works went all over the state to recruit them for work in the shipyards.

"It is no military secret that during the coming year [1943] increasing numbers of women persons not now engaged in essential war work and handicapped persons must take their places on the civilian front,” the Lewiston Daily Sun reported.

The theme of the 1942 Maine State Federation of Labor (MSFL-AFL) convention was “Patriotism” and delegates pledged to support a wartime “no strike” policy and full committed to "cooperation between industry and labor in the production of all defense materials and supplies.”

Furthermore, MSFL Vice-President Horace E. Howe announced that the AFL “will not tolerate communism, nazism [sic] or fascism within its ranks." He warned the convention delegates of Fifth columnists and “yellow men” who “extend the hand of fellowship and cooperation while the other hand holds the dagger.’”

"There is no room for any fifth columnists in the ranks of labor and wherever we find them in these organizations we should take the proper steps to get them out and put them where they belong,” he proclaimed.

Like during World War I, the MSFL Executive Board called on unions to set up committees to investigate “subversive elements and activities” and to urge all non-citizen workers to become naturalized. The Maine State Labor News regularly printed the FBI's message: "If you See a Saboteur or Spy please Call the FBI COLLECT, Augusta, Maine 0280 Liberty, Boston 5533.”

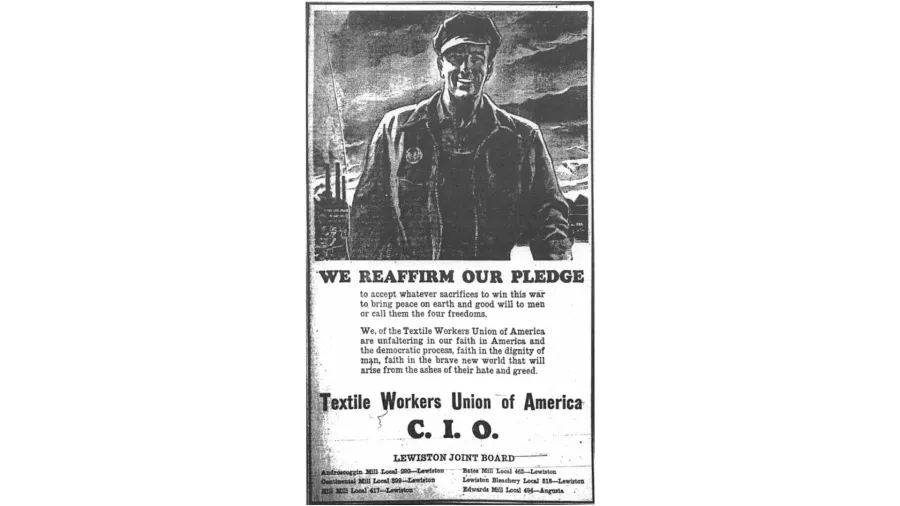

George Jabar, the Maine State Director of the Textile Workers Union of America (TWUA), CIO, echoed patriotic calls for workers to get behind the war effort.

“We laboring people realize that we live under the greatest government of the world. We know what has happened across the waters,” he told members. “There are no unions in Germany, Italy and Japan. Only in this country do we have the right to organize freely and to bargain collectively ... our only ism must be Americanism ... no sacrifice can be too great so long as our flag may wave and freedom reign.’”

The Bureau of Public Relations of the War Department provided Maine unions with a list of War Department films for viewing such as The Army Behind the Army, which promoted the critical role of workers in supporting US troops on the frontlines. In the shipyards workers repeated the “Shipbuilder’s Creed," stating that they would not miss a day of work and “every extra day off is a red letter day for the enemy!”

“I solemnly pledge to devote every working moment to the task given me by the United Fighting Forces,” went the “Shipworkers’ Pledge.” “I pledge to extend my effort to do my job well, so that I may never have it on my conscience that I caused one soldier, sailor, marine, or coast guardsman to die.”

As Maine labor historian Charlie Scontras Scontras observed, the war effort highlighted “the indispensable role of labor in the production process and the winning of the war, and by doing so reinforced workers’ claim to their historic role as the ‘producers' of wealth.”

Local S6 & the Spirit of the CIO: "The Hicks Beat the City Slickers!”

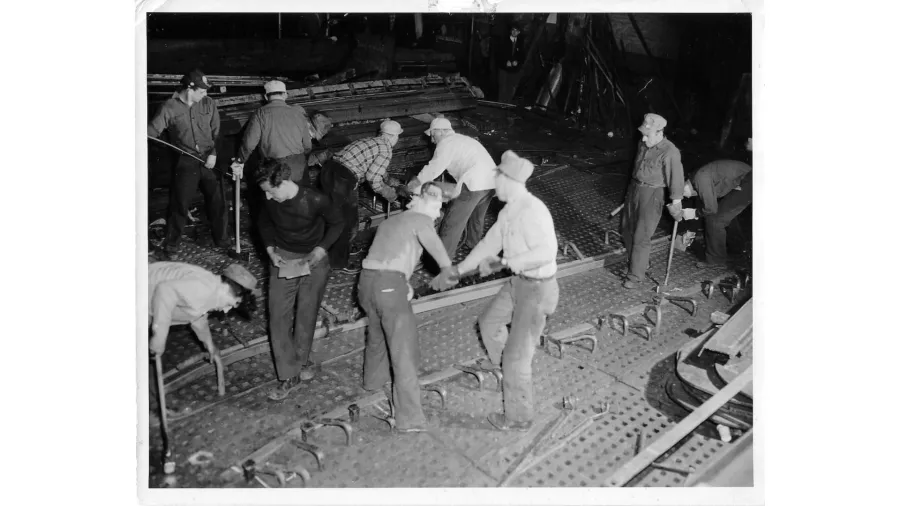

PHOTO: Bath Iron Works, Oct. 1, 1941.

In the early spring of 1940, a year and a half before the US entered World War II, there was a record 2,242 shipbuilders working on five destroyers at Bath Iron Works— far exceeding the number employed at the yard during World War I. Shipbuilder Hermon Coombs recalled in an 1972 interview that the company was desperate to hire workers to fulfill its lucrative wartime contracts.

“BIW went all over the state holding sessions to get people to come into the plant to work, practically begging them to,” said Coombs. “'Course we was putting a ship overboard, delivering ship every…seventeen days. And that was quite a feat, you know.”

By 1941, the workforce had nearly tripled with 6,000 workers at Bath Iron Works building destroyers and merchant ships. Although the pro-CIO shipbuilders led by the militant welders had narrowly lost their first union election in December 1938, by the spring of 1940, Industrial Union of Marine and Shipbuilding Workers of America (IUMSWA) Local 4, CIO organizers had signed up enough worker to hold another election.

In the previous election, Local 4 filed charges against the company for supporting the International Brotherhood of Boilermakers, a more conservative and company-friendly AFL union. As a result, the company was forced to post a notice declaring that it would follow the law and not discriminate against IUMSWA members. In 1939, the AFL-affiliated International Association of Machinists set up a headquarters in Bath, but did not garner enough support to enter the union election of 1940. Local 4 was the only union on the ballot.

However, immediately before the election, the company announced wage increases and vacation pay. Just like in 1938, this classic anti-union trick worked and IUMSWA lost by just eight votes, 1,153 to 1,145. The failure of the CIO organizing drive was not necessarily an indication that a majority of workers opposed forming a union, but many thought the CIO was too radical.

Arthur Lebell, President of Local 4, said more and more workers became interested in unionizing after being passed over for bonuses due to favoritism.

“See before they had the union, a fellow'd go in there and he’d work a week or two, or two or three weeks something like and some foreman or lead man would take a liking to him. He'd take and lay a man off that had a year or two of experience, see,” explained veteran shipbuilder Walter McMann in 1973. “He’d keep this other man, because he was a good friend. Union stopped that, they went to straight seniority."

Shipbuilder Hermon Coombs agreed. “You're thrown on the mercy of the company, and that's all,” he said. “If the company thinks you should have a little more they'll give it to you…Well, the main thing, a union eliminates favoritism.”

Shipbuilders also complained about a company policy that mandated they be fired if they were absent for two days a month. Another grievance was that they were sent home without compensation during inclement weather, even if they had traveled great distances.

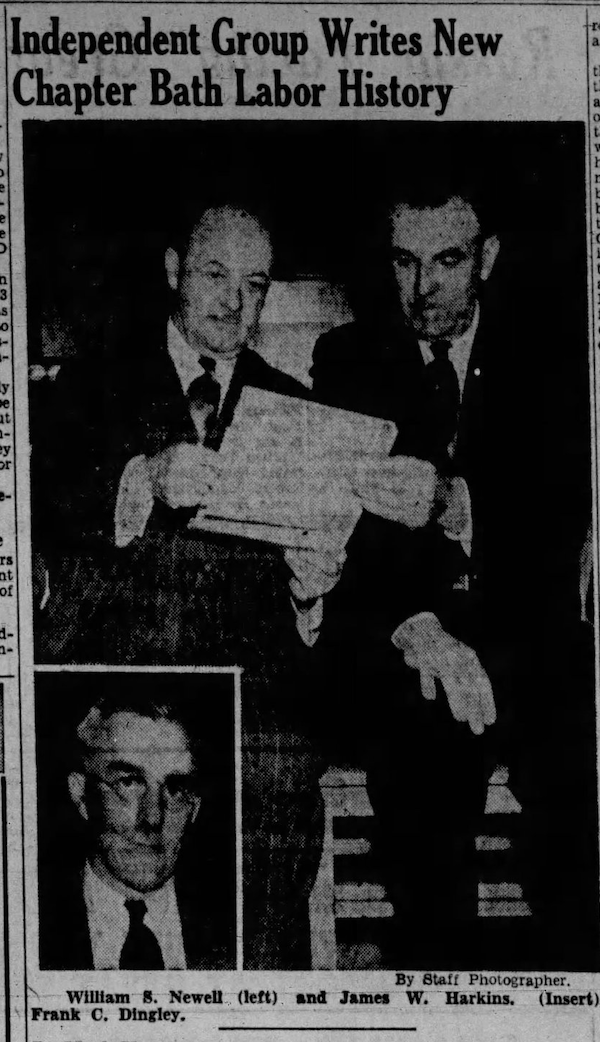

A year later, in 1941, the CIO once again signed up enough workers to hold an election. However, this time around they had to contend with Independent Brotherhood of Shipyard Workers, a new independent industrial union that was organized to defeat the more militant union. When national CIO officials came to Bath to support Local 4, they learned that management tried to persuade a CIO member to form an independent union that would be funded by BIW President William S. Newell, according to labor historian Charlie Scontras.

According to the Portland Press Herald, the Independent Brotherhood was born in late 1940 when shipbuilder Jim Harkins expressed concern over reports that 23 plants engaged in defense work were tied up by strikes. Harkins, a 36 year resident of Waldoboro and father of six children, had worked many years in quarries all over the country. The paper described him as "a quiet, studious type," who had "observed all sorts of unions" and wanted a less militant alternative to the CIO. He had three sons who were eligible for military services and he feared the "sort of hell it would be for his boys at the front" if wartime production became tied up by strikes.

"Somebody mentioned an independent union that seemed to be doing all right at the Electric Boat plant at Groton, Connecticut, which was turning out submarines in great style, and the small group sitting on steps and timbers with their lunch boxes decided to find out what made the Groton union successful," wrote the Press Herald. "They found out and went to work to establish a similar union at the Bath Iron Works. ..The small group figured the Brotherhood had a chance."

The Independent appealed to nationalist sentiment as anti-CIO elements branded IUMSWA organizers as “outside agitators” and “communists.” The Independent Brotherhood contrasted itself as the more patriotic alternative and prominently displayed the American flag on its buttons. IUMSWA countered by charging the Independent Brotherhood with “Desecration of the National Flag. It accused the union of “using the flag to exploit such promiscuous display of pseudo-Americanism."

The CIO-leaning Shipyard Worker reported that the Independent Brotherhood, by its own admission, was a funded by the company. Unlike the more aggressive IUMSWA, the Independent union used much more moderate proposals to attract members, such as full pay for workers who were out sick on accident compensation and a ten percent discount at local Bath businesses.

The new election was to be held on June 25, 1941, and this time President Newell promised he would negotiate with IUMSWA if it polled a majority. However, Local 4 leaders accused the company of deploying its salaried employees to wage “a campaign of vicious slander and intimidation” against IUMSWA members that was "unrivaled in its history.” Local 4 filed charges of "company unionism" against the Independent union and won in an NLRB decision. The ballots were impounded on the eve of the election. When the new election was held on August 12, 1941, the Independent Brotherhood handily defeated IUMSWA Local 4 with 2197 voting Independent, 1094 for IUMSWA and 291 voting no.

Local 4 immediately filed unfair labor changes with the NLRB alleging that the Independent Brotherhood “was assisted by the company” and was therefore a company union. This time the charge was dismissed. When the Independent union signed an agreement with the company for a "union shop," the CIO called for a new election, but again it was soundly defeated, by a margin of 3,182 to 2,310.

The Portland Press Herald reported that “unbiased observers” saw the election as rival unions offering the same things to shipbuilders. But Independent Brotherhood supporters reportedly saw it as a struggle between the "City Slickers" and "The Hicks.” The day after the election a big banner was hung in the Brotherhood’s union hall with the words: "The Hicks Won."

Scontras noted that workers were skeptical of the CIO because of a recent surge in coal strikes and the violent 1937 Lewiston-Auburn shoe strike that ended in defeat for the CIO. The Maine State Federation of Labor (MSFL), the state AFL federation, blamed the "radical" CIO on the Independent union's victory. The CIO’s organizing methods, it argued, succeeded in “gumming up the works,” so that workers became disgusted with both AFL and CIO unions and opted to go independent.

The contract between BIW and the Independent Brotherhood barred strikes, lockouts, work stoppages and slowdowns. The agreement established the Independent as the sole bargaining agent for the employees until 1943. The agreement provided for an open shop security arrangement and made no reference to wages, but did provide for a grievance system, seniority rights, five paid holidays annually, one week's vacation with pay for everyone who had been employed in the yard from eighteen months to ten years, and two weeks for all employed for more than ten years, and a reclassification of employees.”

The new union represented 6,000 workers in the midst of World War II. The pro-CIO workers continued to turn in cards for more elections during the war, but the company dampened support when it extended the benefits won by the CIO in the South Portland yards to Independent Brotherhood members in Bath.

That November the CIO experienced another bitter loss as Independent Brotherhood of Shipyard Workers supporters in Quincy, Massachusetts voted in a landslide, 8,991 to 2564, to defeat the CIO and affiliate with the Independent. An Independent Brotherhood official expressed glee at the CIO’s defeat, telling the Times Record that CIO founder John L. Lewis, the President of the United Mine Workers of America, was “breaking” the CIO’s "own neck" by striking coal mines for a closed shop, where workers would be required to pay dues to the union for collective bargaining.

“[CIO President] John L. Lewis must be shown that he is not a dictator in these United States,” said the official. “It is no use appealing to his patriotism for I don’t think he has any. The closed shop problem seems only an excuse to slow up defense production. If it was a matter of wages there would be some excuse, but none for his dictatorial manner. The sooner the better for this country. His attitude is costing him the support of thousands of workers in his own organization and in the end will result in his tumble from the wall of egotistical ambition with a crash which will leave its bruises on the C.I.O organization for years to come, if it does not entirely kill it.”

But as it turned out, the Independent Brotherhood was a bit hasty in writing the IUMSWA’s epitaph and CIO sentiment remained strong at the yard.

As shipbuilder Hermon Coombs recalled, “It seemed that almost every year we had, welI, should I say an invasion by the CIO trying to unseat the independent.”

When BIW Welders Launched a Wildcat Strike

PHOTO: BIW shipyard workers sweat as they shape steel beams with sledge hammers for a Liberty Ship at the South Portland Shipyard. May 15, 1944. Maine Maritime Museum.

This is the third part in our series about the founding of Local S6, one of Maine’s powerful unions, at Bath Iron Works. You can find part one here and part two here.

On December 21, 1938, shipbuilders at Bath Iron Works lost their first union election to be represented by the Industrial Union of Marine and Shipbuilding Workers of America (IUMSWA), CIO. But while they were down, the pro-union workers weren’t ready to throw in the towel any time soon.

The welders were also the most pro-union shipbuilders because they knew that taking collective action was the only way to force the company to improve workforce safety. As welder and former union leader Arthur Lebel told an interviewer in 1972, the welders’ job was particularly hazardous because they had to work in poorly ventilated areas like the insides of tanks where they were exposed to zinc oxide and other poisonous fumes

“We were more militant than the other groups,” said Arthur Lebel. “The fact of the matter is in a few years after that, the welders organized themselves to a point where they wanted to do something about the conditions. They had no blower systems that take away the fumes from the welding arc and, when we worked in the bottoms of the ship there was no ventilation.”

The following spring of 1939, Bath Iron Works employed a record 2,400 workers at the yard as they worked to complete five Navy destroyers. In addition, the company had two additional bids in the process, but it was also facing the threat of a wildcat strike.

The welders had drawn up a series of demands for BIW, including the installation of a ventilation system, removal of clocks from welding machines and the establishment of a wage scale and classification system to address rampant favoritism at the yard. Although they didn’t officially have a union at the time, welders set up a meeting with BIW executives to present their proposals.

“I think we negotiated for five weeks and they agreed that our cause was just, that we should have more money, and that we should have better conditions, but they never gave in on a single item,” Lebel recalled. “ I think then that the welders got together and they decided to give the company a twenty-four hour notice that if we didn't get a realistic answer to our proposals that we would call a cessation of work.”

The welders were infuriated when all they received back from the company was a written statement on a plain piece of paper that didn’t even acknowledge their grievances. To preserve their "dignity and self-respect," the welders and tackers laid down their tools in a near unanimous action. The "dirty dozen” who scabbed during the strike were sent out to "mix" with the strikers with "more vague company promises" to try to get the men back to work.

PHOTO: The Peoples’ Baptist Church in Bath where the strikers at BIW held their meeting in the spring of 1939.

A federal mediator was eventually brought in to meet with both sides. Finally, the company agreed to some of the workers’ demands. The strike lasted for two and a half weeks.

“A federal mediator was sent in [and] we was able to re-classify not only the welders but the entire yard,” said Lebel. “And I recall at the time that the raises averaged from two cents an hour to thirty-six cents an hour. I think a man named Sidney Bean got a thirty-six cent an hour raise and they installed a fifty thousand dollar ventilating system, which I dare say has saved hundred of lives since that installation.”

As a result of the strike, the company also finally agreed to scrap its arbitrary piece work system for paying welders and established rates per foot. The company also agreed to give the workers lockers to store their gear instead of having them keep it in the blacksmith shop as they had prior to the strike.

“They put their arms around our neck and said, ‘well, you've done a good job and from now on if anything is wrong come and talk to us about it,’” Lebel added.

However, as Maine labor historian Charlie Scontras noted, the welders failed to win time and half for Saturdays despite the fact it was the practice at other shipyards. The workers’ pro-union newspaper The Shipyard Worker wrote that the yard “reeks of favoritism" because workers still didn’t have seniority rights. The company also found loopholes to avoid living up to its promises. BIW fattened its bottom line by demoting workers from a mechanics rating to that of a lower-paid handyman or helper.

The Shipyard Worker argued that the company and “its humble and obedient” The Bath Times newspaper continued to spread rumors of layoffs to intimidate workers and cultivate a “slave psychology” among the men. As the war raged in Europe, BIW’s profits soared thanks to war time contracts and industry-low wages paid to shipbuilders. As the Shipyard Worker asked its readers in April, 1940:

Why then should not the workers who build the ships share in this prosperity?

Why should the B.I.W. be one of the few yards to refuse to grant a wage increase in the last several months?

Why should the B.I.W. be the only yard without paid vacation?

Why should the B.IW. openly flaunt the seniority rights of its employees?

The answer was abundantly clear: “Organize.”

PHOTO: Two of the seven Bath Iron Works destroyers transferred to the Royal Navy in the Destroyers for Bases Agreement. The outboard ship made the St. Nazaire Raid. Photo by C.J. Ware, Royal Navy official photographer.

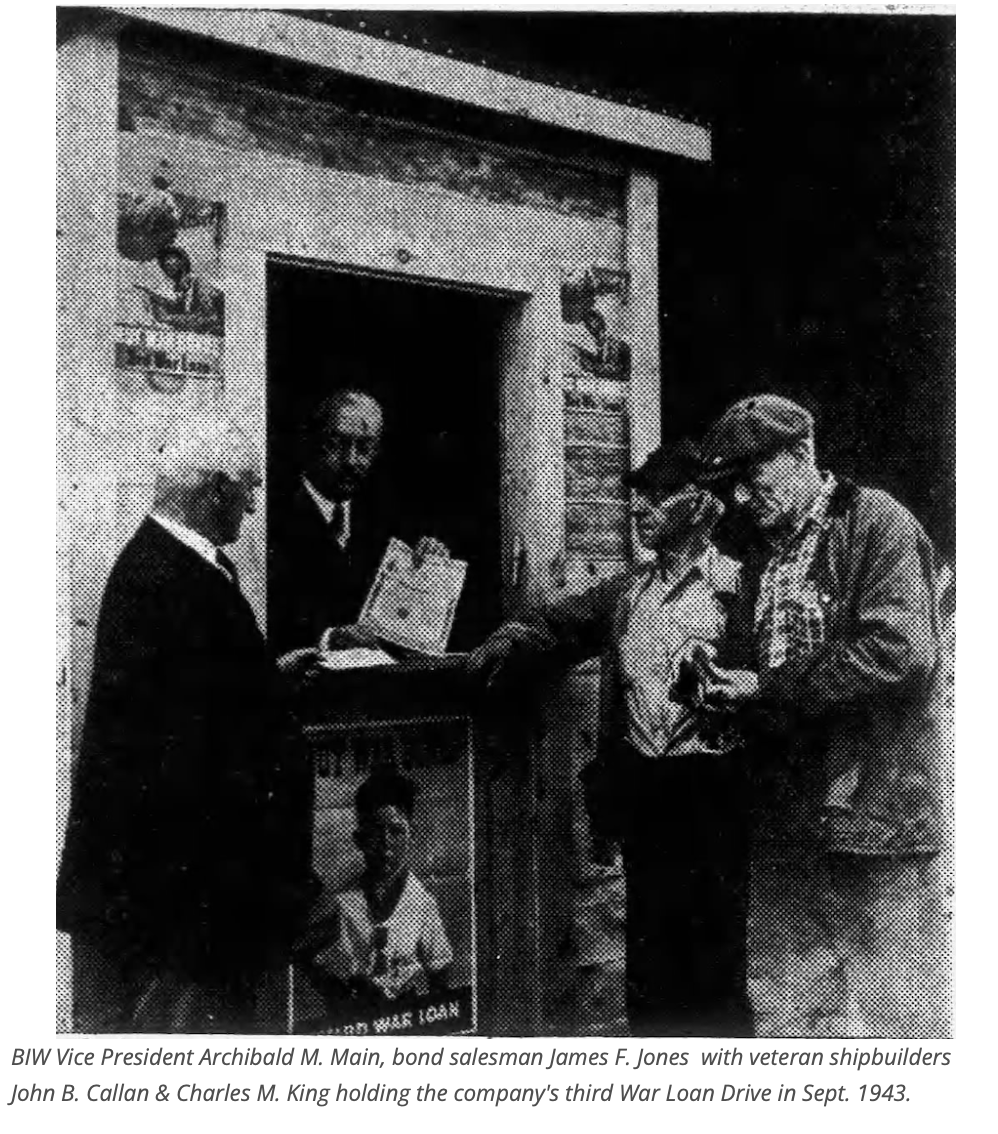

In the spring of 1943, Bath Iron Works was humming with activity as nearly 12,000 men and women worked day and night to build warships to defeat the Nazis in Europe and the Japanese in the South Pacific. By June 28, 1943, the company launched its eleventh destroyer of the year, the Ingersoll, in a ceremony that included British Ambassador Lord Halifax, Under Secretary of the Navy James Forrestal and numerous other dignitaries, diplomats and Navy bigwigs. After the Ambassador inspected the ships at the yard, he passed the evening as guests of BIW President William Newell and his wife.

“One thing is certain," wrote the Bath Daily Times of the event, "the reputation which Bath has made down through the years for building ships, whether for cargo carrying, pleasure craft or naval service, has gained rather than deteriorated and with the frequency with which we are launching naval craft, about two weeks apart, we certainly feel that we are doing our bit toward winning the war."

On the surface, labor relations appeared to be running smoothly with the 1941 victory of the company-friendly Independent Brotherhood of Shipyard Workers over the more militant CIO affiliate, the International Union of Marine and Shipbuilding Workers (IUMSWA). The Independent Brotherhood’s success helped pave the way for other shipyard workers up and down the east coast to go independent. Jim Harkins, the founder and first president of the Independent Brotherhood at BIW, was instrumental in founding the “East Coast Alliance of Independent Shipyard Unions of America,” an alternative to the warring AFL and CIO factions.

In February of that year, the pro-business Lewiston Sun Journal applauded the Independent Brotherhood for working collaboratively with BIW. The editor contrasted the labor climate in Bath to Detroit where 6500 UAW workers in the gear and axle division of General Motors broke a wartime “no strike pledge” and walked out in a dispute over the rate of production of certain parts. The LSJ blasted the CIO autoworkers for allegedly stopping the production of army jeeps while the Independent Brotherhood in Bath brought its concerns about wages, sick leave, vacation pay, lunch breaks and other contract disputes to the War Board’s Shipbuilding Commission.

“Even though the contract was not renewed in June because of differences, the workers at the Bath Iron Works stayed on their war job of turning out destroyers for the Navy,” the editorial continued. “Apparently they believe as this column has maintained that no strike can be justified now regardless of what the circumstances may be, for our nation is engaged in a gigantic war which demands of industry’s wheels.”

But not everyone was happy and contented among the men and women who built the ships. Many shipbuilders, especially the welders, felt that the Independent Brotherhood was not doing a good a job representing their interests and easily caved to company demands.

Despite President Roosevelt's famous denunciation of war profiteers on the campaign trail in 1936, defense industry profits were soaring at the height of World War II. In 1942, the House Naval Affairs Committee singled out Bath Iron Works among a handful of other defense contractors for raking in “excessive and unconscionable” profits. The committee report found that BIW had earned profits of $850,000 to $1.13 million ($15 to $20 million adjusted for inflation), 8 to 29 percent, on eight contracts. The following year, in 1943, BIW hauled in a record $3.7 million profits, roughly $64,681,000 in today's money.

Shipbuilders saw those figures and wondered why they weren’t getting their fair share of these lucrative contracts. CIO supporters hoped to finally win an election with the more militant IUMSWA so they could take on the company. However, out of 9,000 eligible voters, the Independent Brotherhood ended up once again crushing IUMSWA, 5,072 to 2,111, with 294 workers choosing the AFL and 59 voting ‘no’ to all three unions.

The Strike Summer of '44

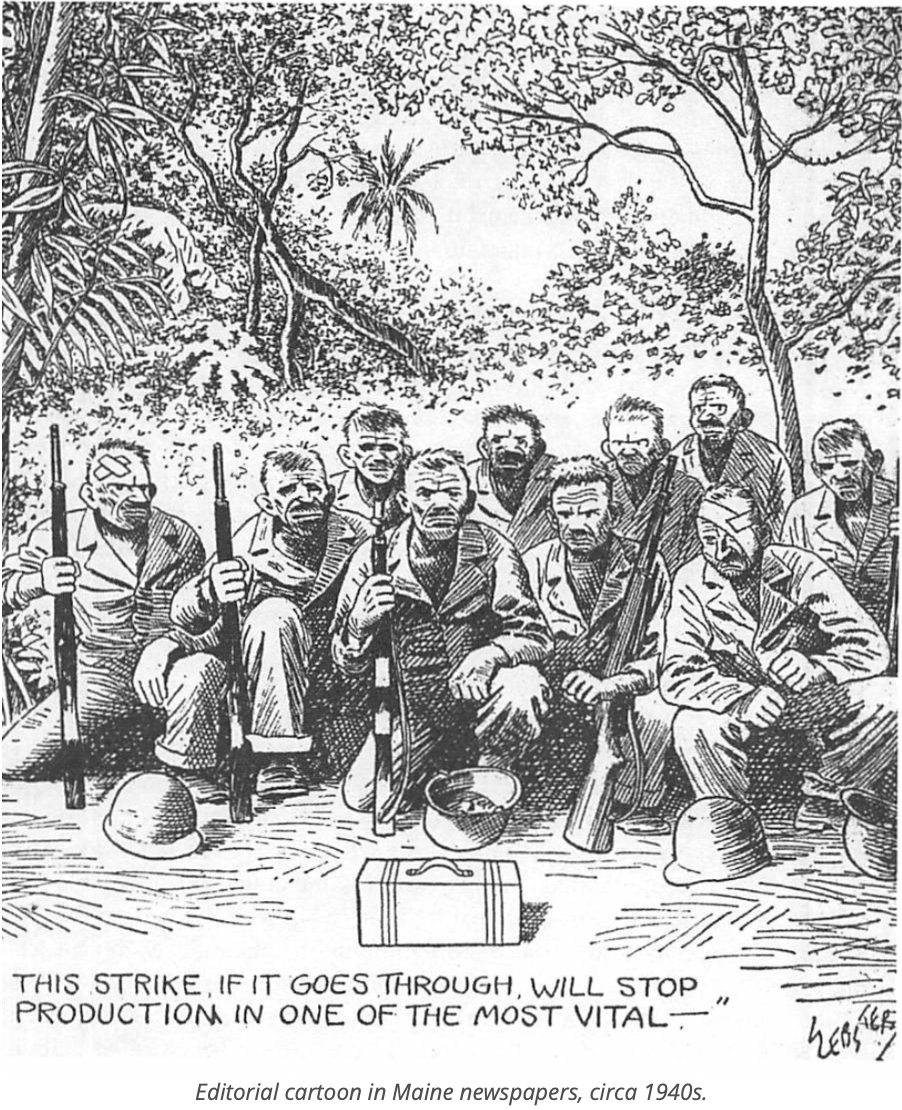

In spite of their losses, the radical CIO welders continued to be a thorn in the side of both the company and the leaders of the Independent Brotherhood. From the summer to the fall of 1943, the shipyard was rocked by a series of unauthorized wildcat strikes.

On May, 31, 240 welders on the night shift walked out after the demotion of a few supervisors and the dismissal and suspension of a welder after a party. The company responded that it would reinstate the welder with a warning and that the other cases were “under discussion.” The strike ended with an ultimatum for the welders to return to work as they had violated the union's "no strike" clause. The Independent Brotherhood placed the blame on CIO sympathizers for stoking the unrest while CIO representatives said that, far from supporting the strike, the union was doing all it could to get the strikers to go back to work.

Then in mid-August, another 150 welders walked out to protest being reassigned to the 4pm to midnight shift without their consent or regard to seniority. The wartime walkouts were condemned by local newspapers and prominent men in the community. Father Timothy C. Maney at St. Mary’s Catholic Church in Brunswick “soundly berated” the strikers in a Sunday sermon. He contrasted their behavior with a local man named Bobby Hawks, who had been serving on the frontlines “calmly and uncomplainingly” accepting “24 hour jobs that might bring death at any moment.”

While the welders drew “high salaries” of $18 dollars a day and complained about their long hours, wages and scheduling, he continued, “the American boys, on the fighting fronts, were the only ones who had the privilege to complain, but you never heard anything from them.” He didn't mention the massive profits President Newell and his shareholders were raking in.

“Look at Bobby Hawks,” said Father Maney, not realizing Hawks himself was sitting in the pews. “For three years he has been in the fight. He’s been up and down the Pacific, in the thick of things. You didn’t hear anything about his working too long hours, about the poor pay he was receiving, about how he’d like a change in schedule. You haven’t heard of him going on strike.”

With a weak pro-company union, President Newell knew that he had the strikers over a barrel. Their most effective leverage was to strike, but they would face withering criticism that they were selfish, unpatriotic and un-American. Independent Brotherhood officials preferred that the workers stay at their machines and let the leaders take grievances before the National War Labor Board, a 12-member arbitration board of businessman and labor representatives established to mediate labor disputes during the war. The War Labor Board essentially replaced collective bargaining during the war because it could intervene in any labor disputes that it saw as endangering "the effective prosecution of the war" and impose a settlement.

Then in the early morning hours of Saturday, September, 30, 1944, 2000 shipbuilders, nearly every worker on the day shift, walked off the job in protest over BIW's delay in implementing an incentive bonus plan for hourly workers. By noon, 95 percent of the workers were out on strike. The Regional War Labor Board immediately called for the Independent Brotherhood to end the strike in compliance with the no-strike agreement because it interfered with "vital materials needed by our armed forces.” Independent leaders quickly met with the strike leaders in the "emergency committee" to hammer out a compromise.

Harold H. Chadburn, President of the Independent Brotherhood, acknowledged that there was “gross inequality in the take-home pay of employees.”

“We will do all in our power to bring the true facts before the management and process them through agencies according to government law," he told the press. "A referendum seems to be the best to determine the wishes of the majority."

As part of the t "return-to-work" agreement, the company agreed to send different options for the new bonus incentive plan to the workers for a referendum. The referendum asked whether the workers desired to continue the present individual departmental contracts; change to an overall blanket contract affecting all employees on an equal basis; or whether they wished to accept the management's bonus covering hulls completed since last July 8 and payable Nov. 29.

The workers also faced intense pressure from the government as State Selective Service Director Harold M. Hayes immediately requested the names, addresses and other information of all male employees ages 18 to 37 who did not return to work the following Monday. By leaving their jobs and striking, the men were now eligible to be drafted into the war. By Monday, the strikers were back at work and the plant was once again running at full capacity.

On October 10, the shipbuilders turned down a recommendation from the War Labor Board and voted in favor of an an incentive pay plan that would include all of them equally, so that every worker would share in savings on each ship delivered by the yard. One of the main complaints of the Bath workers during the work stoppage was that some employees were receiving incentive pay bonuses, while workers in other departments were still waiting for incentive pay in their department. The vote, at least temporarily, resolved a lot of the frustration in the yard over the company bonus pay system, though electricians were reportedly unhappy with the deal and briefly threatened another walk out.

It's possible that the company and the union could have prevented a lot of the unrest had it engaged with the rank and file workers and negotiated the compromise in the beginning, but in typical fashion, the Lewiston Sun Journal put the blame solely on the strikers.

“Until this strike, employees at the Bath Iron Works had been turning out destroyers with a minimum delay from labor troubles,” the editorial grumbled. “It is to be hoped they will return to that policy and will not again bring construction of destroyers to a stand still. The lives of too many American fighting men depend on those Bath destroyers to warrant any strike here.”

As the Allied Forces closed in on Germany in the spring of 1945, more unrest would bubble up on the home front in the little shipyard in Bath, Maine.

Organizing the South Portland Shipyards

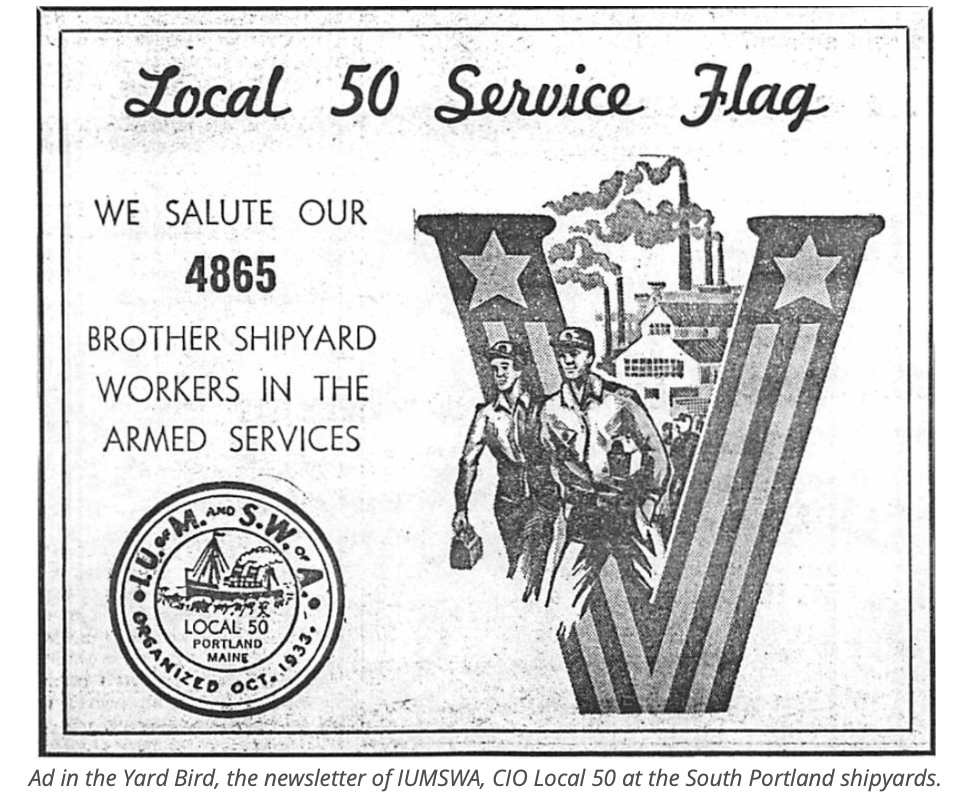

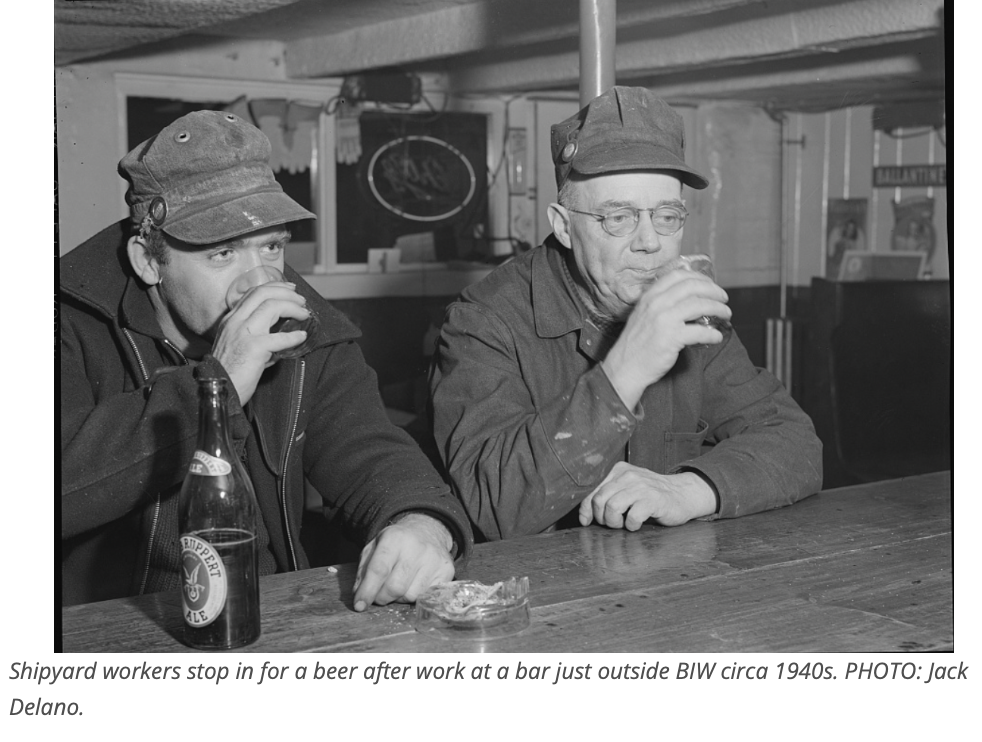

PHOTO: IUMSWA Local 50 ad in the CIO newspaper the Yard Bird, which was circulated in the South Portland shipyards in the early 1940s.

In the fall of 1941, Bath Iron Works welder and CIO union organizer Arthur Lebel headed forty-four miles down the coast to South Portland to set up a new office for his next organizing drive. Months earlier he and his CIO brothers and sisters suffered a heartbreaking defeat to the new Independent Brotherhood of Shipbuilders, a more company-friendly union that eschewed strikes and shied away from confrontation with the company.

“I was the first one there [at the South Portland yards], and I think I was the key organizer there,” recalled Lebell in a 1972 interview.

Lebel was determined that this time would be different. He and his colleagues brought in a typewriter and a mimeograph machine and ran off thousands of leaflets to distribute at the gates of the South Portland yards.

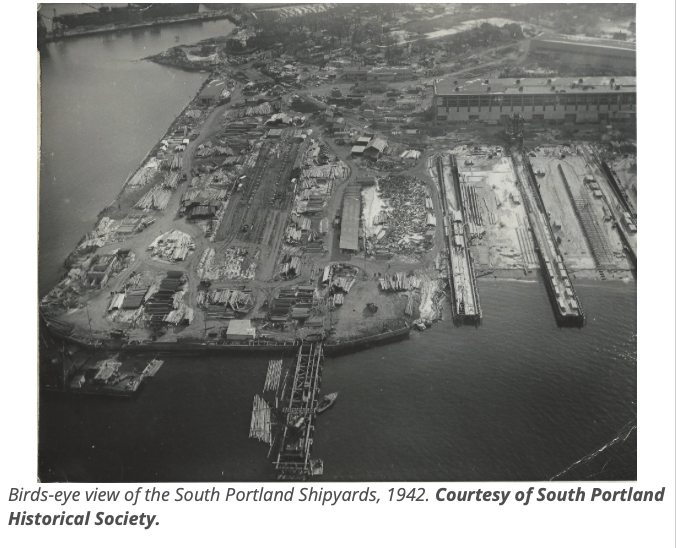

The previous year, union construction workers began work on the Todd-Bath Iron Shipbuilding Company (TBISC), known as the East Yard, for the construction of freighters for England on the South Portland waterfront. The adjacent South Portland Shipbuilding Company (SPSC), known as the West Yard, also began construction on a new yard to build cargo ships.

By the time Lebel arrived, there were about over 6,000 workers at the two South Portland yards and 6,000 at Bath Iron Works. The three companies had hired a whopping 10,200 shipbuilders in just two years. Shipbuilders complained that they were earning less than other workers in the defense industry. The cost of living was surging and affordable, quality housing was very hard to find.

Horace Howe, president of the Portland Central Labor Union, and Vice President of the Maine Federation of Labor, noted that there was no standard for the crafts at the yard and some machinists were making as low as 66 cents an hour, $13.79 in today’s dollars. Workers also complained of the lack of parking spaces to accommodate the thousands of commuters. While Todd- Bath management had their own reserved parking spaces, the shipbuilders received "continual tickets.” It was the perfect union organizing opportunity and the elections were hotly contested.

The Portland Central Labor Union was not about to let such a massive workforce become enticed by the promises of the International Union of Marine and Shipbuilding Workers (IUMSWA), CIO. But the two rivals found common cause in their passionate loathing for the Independent Brotherhood, which claimed it had 3,500 members at Todd-Bath. The AFL and CIO called it a “company union” to anyone who would listen.

The AFL argued that "the fact that the president of the independent union does his organizing work on the company’s time, indicates that the shipyard organizations are company and not independent unions.” The powers that be certainly favored the Independent Brotherhood. After the Independent Brotherhood held a meeting at the South Portland City Council Chambers, the CIO was denied use of the venue on the grounds the chambers were for local organizations only,” wrote Charlie Scontras in his book “Labor in Maine: Building the Arsenal of Democracy.” The denial was yet another example of how CIO supporters were treated as “outside agitators” rather than the local workers that they were.

During the BIW union drives, Todd-Bath President William S. Newell, who was also president of BIW, made no secret of his support for the the weak Independent Brotherhood and even helped fund its successful union drive at BIW. In those days, defense industry contractors knew that their workers would eventually unionize, so they tried to sway them to choose less militant options.

As Scontras wrote, members IUMSWA Local 50 distributed leaflets and held meetings in both English and French, not only in the South Portland area but also in Saco, Biddeford, Sanford and other towns where shipbuilders lived. At the meetings, the workers played union records and sang rousing labor songs. CIO members called for the creation of housing committees for Portland and South Portland and demanded that workers have representation on these boards.

They also accused the company of hiring learners who deprived first class mechanics of work. “Favorite sons,” they argued, were given all the overtime works at the expense of seniority. CIO leaders said the company classified everyone in the outside hull department — with the exception of the chippers, drillers, riveters, and a few other outstanding crafts — as shifters' helpers. As a result, whole job classifications were eliminated resulting in wage cuts.

The CIO also took aim at the Independent Brotherhood’s contract with BIW that ensured Bath workers would not lose their seniority if transferred to the South Portland yard. This meant South Portland workers could be replaced by Independent Brotherhood members when work was slack, undermining job security in favor of "the inner circle of the Bath company union.” The CIO ridiculed the fifty cents a month dues required by the Independent for “misrepresentation.” Meanwhile, the company was raking in massive profits from government contracts.

Lebel recalled workers coming into meetings to learn more about the benefits of unionizing with the CIO. Soon they were forming organizing committees in each department and workers began wearing buttons and signing authorization cards.

“We talk about the conditions under which the people are working,” said Lebel. “We compare the wages with unionized shipyards and let the workers think about it and make a decision. And it's just like any election process, you put your best foot forward and, you don't make any promises to the workers, but you point out what they can do if they band together.”

The union election for Todd-Bath workers was to be held on March 12, 1942, IUMSWA, CIO, AFL Metal Trades unions and the Independent Brotherhood were all on the ballot.

A week before the election the 60,000-member Maine AFL’s news organ Maine State Labor Newsran a headline expressing confidence that South Portland workers “will not vote for the Communist-Dominated” CIO alongside a photo of a violent strike with the caption “Authentic Picture Taken During a CIO Strike.” The sub-head blared:

“Maine Workers Regarded as Too Intelligent to Become Tied Up With An Organization That Sponsors Sit-Down Strikes and Other un-American Methods During Controversies — Recall How CIO Reversed Anti-Defense Policy When Nazis Invaded Russia, and Also Its Fight to Free Browder and Persistency in Keeping Communists and Fellow-Travelers in Office"

However, the AFL’s red-baiting failed. When all the ballots were counted, 3,620 workers voted for the CIO, 1,529 for the AFL, 513 for the Independent Brotherhood, and 353 for no union out the 8,614 eligible voters. After years of false starts, the CIO supporters had overwhelmingly won their first union election at a Maine shipyard.

This time the company surprisingly remained neutral in the election, which Lebel attributed to high profits. The Shipyard Worker reported that Todd-Bath was resigned to the fact that the CIO would win the election and “therefore there has been no intimidation or coercion whatsoever on the part of the foremen and other company men to force our men to remove their buttons.” Scontras noted that CIO buttons were seen everywhere from the streets and buses to restaurants, and clubs. The victory was so overwhelming, according to some workers, that the ground was covered with AFL Buttons "which had been thrown away by men ashamed to be seen wearing them,” wrote Scontras.

On May 4,1942, IUMSWA Local 50 and Todd-Bath signed a new contract that included a raise from 66 cents to between 72 and 78 cents an hour, a dues checkoff system, grievance procedure; seniority provisions, one-week vacation for those employed for one year, and two weeks vacation for those who were employed for two years or more; time and a half on Saturdays and double time on Sundays, and on nine specific holidays.

The contract included a no-strike or lockout provision for the term of the agreement and created a closed shop where dues were compulsory as a condition of employment. The workers agreed to waive vacation time and instead took their vacation pay in the form of war bonds and stamps. Employees who were drafted into the war were given bonuses. The contract was followed by the reclassification of all employees of the Todd-Bath shipyard which meant pay increases, depending on the skill and ability of the individual employee.

Some workers who voted against IUMSWA were not happy to learn that they would be obliged to join the union or leave the yard. As Scontras notes, some questioned how the CIO could declare a “closed shop” during war time when all hands were needed on deck. IUMSWA countered that they could keep their AFL cards as long as they paid CIO dues.

"It's about time we found out who is running the country—the Government or the CIO. We've all heard the slogan 'No walkouts. No lockouts, No strikes in war time,' but this looks every much like a lockout when they can tell us where to work,” one disgruntled shipyard worker bitterly told a reporter. He added, "I don't know who's to blame,” but it looks to me as though it were Pres. Newell."

As Scontras noted, the comment blaming Newell for the CIO victory could be traced to the fact the BIW President actually encouraged his workers to join unions and was outspoken in his acceptance of the closed shop. In all likelihood he changed his position to create a more stable, predictable and harmonious workplace free of labor strife so he could meet tight contract deadlines.

After all, the Independent Brotherhood’ proved it could not control the wildcat strikes that rocked the open shop BIW shipyard that year. At the time, Newell's acceptance of the closed ship was an unprecedented decision by a corporate executive in Maine because the open shop was seen as the “hallowed principle in labor-management relations,” wrote Scontras. At the same time, Newell also provided the same contract gains that the IUMSWA won in South Portland to BIW workers — a move that the CIO viewed as an effort to prevent it from organizing the Bath shipyard.

AFL organizer and leader Alonzo Young believed the odds “were too great” for the craft unions to beat the industrial IUMSWA. The Maine State Labor News argued that CIO had a longer presence at the yard and it was able to out-organize the AFL union. The CIO reportedly had 300 full and part-time” CIO workers stationed inside and outside the yard to engage workers.

Others "rang door bells all hours of the day and night during the entire organizing campaign” while the CIO targeted welders, burners and tackers with large ads in daily newspapers stating the AFL had refused to charter them into an international union. Unlike the CIO, the labor paper complained, the AFL had run a "clean-cut campaign” which contained no "abusive" statements about the CIO.

Although the AFL had suffered a series of defeats at Maine shipyards, it wasn’t out of the game. In a forthcoming installment in our history of shipbuilder organizing in Maine we will cover the AFL’s spectacular comeback at the nearby SPSC yard.