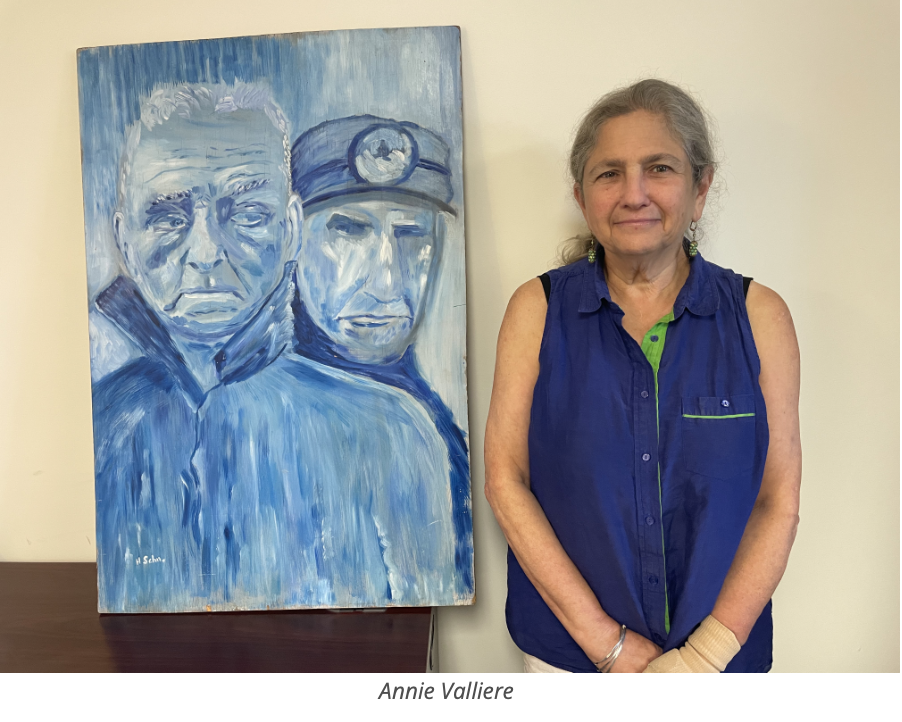

Mainer Annie Valliere Remembers Her Great Aunt & Labor Leader Rose Schneiderman

Annie Valliere of Bath is a retired school therapist and labor folk singer who has sung all over Maine at union rallies, demonstrations and even at a Maine AFL-CIO Labor Summer Institute many years ago. She attributes her passion for the labor movement to the influence of her beloved great aunt Rose Schneiderman, one of the most influential labor leaders and women’s rights activists of the 20th century.

In an essay Valliere wrote in the book “Talking to the Girls: Intimate and Political Essays on the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire,” she recalls her great aunt in her later years as “small even by child standards.” She should stood at just 4 foot 6 inches tall with flaming red hair, but Rose Schneiderman more than made for her small stature with her powerful voice. She enjoyed books on the classics, history, politics and poetry and loved to give them to the younger women and girls in the family. Schneiderman always told them to stand up for themselves, Valliere recalled.

Rose was also very stubborn, which served her well in leading labor struggles in the early part of the 20th century. For Valliere, she was both “adorable and intimidating.” One day, when 11-year old Annie brought her cookies, her aunt bluntly told her she didn't want them and to give them to someone else on her floor. She could be harsh, but Valliere believed she thought she was helping raise “strong and independent girls.”

“She had spent so many years, instructing, urging, organizing and mentoring women,” Valliere wrote. “ She must have felt very passionate about putting those same efforts into the girls and women of our family.”

A Childhood Lost

Born to devout Jewish parents in 1882 in Poland, then part of the Russian Empire, Rose was eight years old when the family was forced to emigrate to the United States so her father Samuel could escape the military draft. In an effort to “de-Jewify” young Jewish men, Russia required Jewish men between the ages of 12 and 43 to serve in the Russian army for 25 years, writes Valliere. Males like Samuel who were the only sons in their families were exempt from the draft, but a wealthy Jewish family purchased Samuel’s exemption for one of their sons so he has conscripted. Jews were not allowed to leave the Russian Empire, but Samuel was able to flee to America. Rose’s mother Dora and the children managed to slip across the border and follow him.

“I still hold the image of Dora hiding the youngest, Charles, under her shawl so that his chatter would not be heard by the guards as she and the children slipped through the Polish-German border,” writes Valliere.

As asylum seekers living in a one-room tenement in Manhattan’s Lower East Side, the Schneiderman’s struggled to stay afloat. Then Rose’s father died of meningitis two years after the family arrived, leaving his pregnant wife and three children. Dora worked nights, took in boarders and did sewing and washing for neighbors to cobble enough money to pay for food and rent. But after she lost her night job in 1895, 13-year old Rose was forced to leave school and find a job to support the family while her two younger siblings were temporarily placed in an orphanage.

While her mother wanted young Rose to work in a department store because it was considered to be more “respectable,” factory work paid better than her retail job. Eventually Rose began training to become a cap maker. While working at the cap factory, she grew fed up with the way women were treated and how they were relegated to the worst jobs. It was then that she began learning about progressive ideas like socialism, feminism and trade unionism. Her hardships transformed her to a militant labor activist and feminist. As Valliere writes, Roses' childhood was stolen, which is why she vowed to fight for other women and girls so they didn't have to go through the same mistreatment, long hours, low wages and unsafe and unsanitary working conditions.

She soon became known for her powerful oratory skills and talent for organizing. At the age of 21 in 1903, Schneiderman helped organized her shop with the United Cloth Hat and Cap Makers’ Union, a union founded by mostly Eastern European socialist Jews like herself. She received even wider notoriety after she organized a city-wide capmakers’ strike in 1905 and was elected as secretary of her local and a delegate to the New York Central Union.

By 1908, Schneiderman was elected vice president of the New York Women’s Trade Union League, becoming the first woman elected to a national office in the American labor movement. The Women’s Trade Union League, which the Maine State Federation of Labor affiliated with in 1914, was not exactly a union, but an association of both middle class and working class women dedicated to supporting unionization efforts by women workers, strikes, the establishment of a minimum wage, an end to child labor and other measures to help women and child workers. It was founded in Boston in 1903 after it became clear that the American Federation of Labor would not accept women workers into its ranks.

The following year in 1909, Schneiderman and other young European Jewish women in the International Ladies Garment Workers Union helped lead a strike of women workers at the Triangle Shirtwaist Company and the Leiserson Company. It quickly become a citywide strike that became known as the Uprising of the 20,000. It was the largest strike by American women workers at the time.

Then on March 25, 1911, the devastating Triangle Shirtwaist Fire killed 146 mostly immigrant garment workers, including 123 women and girls. As reports of young women jumping to their deaths and charred bodies piled up at the locked exits of the factory emerged, the horrid conditions for women workers was brought into the national spotlight. 28-year old Rose Schneiderman was on the scene and went to notify the families of the victims.

“We went to the East Side to look for our…. Our workers in the Women’s Trade Union League took the volunteers from the Red Cross and together we went to find them by the wailing in the streets of relatives and friends gathered for funerals,” she wrote. “But sometimes you climbed floor after floor up an old tenement, went down a long, dark hall, knocked on the door and after it was opened found them sitting there — a father and his children or an old mother who had lost her daughter, sitting there silent and crushed.”

On April 2, 1911 at the Metropolitan Opera House, Schneiderman delivered an impassioned speech that captured the pain and fury of the moment:

I would be a traitor to these poor burned bodies if I came here to talk good fellowship. We have tried you good people of the public and we have found you wanting. The old Inquisition had its rack and its thumbscrews and its instruments of torture with iron teeth. We know what these things are today; the iron teeth are our necessities, the thumbscrews are the high powered and swift machinery close to which we must work, and the rack is here in the firetrap structures that will destroy us the minute they catch on fire.

This is not the first time girls have been burned alive in the city. Every week I must learn of the untimely death of one of my sister workers. Every year thousands of us are maimed. The life of men and women is so cheap and property is so sacred. There are so many of us for one job it matters little if 146 of us are burned to death.

We have tried you citizens; we are trying you now, and you have a couple of dollars for the sorrowing mothers, brothers and sisters by way of a charity gift. But every time the workers come out in the only way they know to protest against conditions which are unbearable the strong hand of the law is allowed to press down heavily upon us.

Public officials have only words of warning to us—warning that we must be intensely peaceable, and they have the workhouse just back of all their warnings. The strong hand of the law beats us back, when we rise, into the conditions that make life unbearable.

I can't talk fellowship to you who are gathered here. Too much blood has been spilled. I know from my experience it is up to the working people to save themselves. The only way they can save themselves is by a strong working-class movement.

Scheiderman went on to join the fight for women’s suffrage, ran for US Senate and became a leading figure in feminist and labor politics in New York State. She became a close friend of Eleanor Roosevelt and her husband President Franklin Roosevelt appointed her to the National Recovery Administration and the National Labor Advisory Board where she advocated for equal pay for women and including domestic workers in Social Security. She supported unionization efforts for hotel maids, restaurant workers, and beauty parlor workers. In the 1930s and 40s, Schneiderman was active in causes to help Jewish refugees escape Nazi-occupied Europe and resettle in the United States and Palestine.

Valliere was 18 years old when her aunt Rose Schneiderman died in New York City on August 11, 1972, at the age of ninety. But it wasn’t until she grew older that she learned the details about her aunt’s storied career in the labor movement.

“I think she shows a story that is still needed today — fighting for things that we still don’t have,” said Valliere.