The Maine Workers Who Joined the Uprising of ‘34

When 30-year old George Jabar of Waterville was hired as an organizer for the United Textile Workers of America in 1934, the union didn’t provide any training to help him with the monumental task of organizing the state’s 22,000 textile workers. But although he had to learn the skills on the job, he wasn’t a newbie.

Born to Lebanese immigrants in 1904, Jabar went straight to work at the Wyandotte Worsted mill in Waterville right after high school graduation in 1922. He started in the finishing department as a woolen weaver and was then promoted to walk starter and eventually became a loom fixer, one of the most skilled trades in the mill. From a young age, Jabar developed a strong belief in fairness and justice. His first experience with unionism was when he wanted to play banjo in a band and was asked to join the musician’s union.

But in those days, there were very few textile unions in Maine and those that did exist were typically, “fly-by-night,” Jabar told an interviewer in 1972. Typically when workers would organize a union in the mill, there would be “a little disturbance,” but the employer could just refuse to recognize the union as the bargaining agent for the workers and the union would eventually dissolve. There were a couple of craft unions at mills in Biddeford and Brunswick, but they were small and only represented the most skilled trades like spinners, fixers and weavers. Jabar came out of the woolen division, where textile workers were the most militant.

It was certainly an industry ripe for unionization. Jabar recalled working grueling 55-hour weeks with no benefits like health insurance or paid sick time. When the workers at Wyandotte Worsted organized United Textile Workers Local 1802, he didn’t hesitate to join.

“The way we were working if the boss didn’t like the color of your hair, you was out,” recalled Jabar. “And that alone, in itself, to my way of thinking at the time was worth having an organization, that you just didn't have to come in, go into work and cow-tow to an employer.”

But it was a tough time for organizing. Following the end of World War 1, a massive strike wave prompted a harsh crackdown by business elites and their allies in the government. Media and politicians conflated all labor unions with violence, disorder and Bolshevism. At the same time, companies like the S.D. Warren Mill in Westbrook began pioneering paternalist social welfare programs for workers to soften their image and discourage workers from joining unions.

This was also around the same time that New England’s textile mills began moving to the South to exploit low-wage, non-union labor. The Maine State Federation of Labor (AF of L) reported that union membership in Maine had declined from about 14,000 in 1923 to just 5,524 in 1925. Then in 1929, the stock market crashed, throwing nearly 13 million people out of work, decimating the ranks of organized labor.

“The break in the stock market... was followed by immediate slowing down of industry,” reported Maine's Labor Commissioner in the department's 1929-32 Biennial Labor Report “…Industries have gone on part time, have laid off workers, both in factory and the office, building has come to a virtual standstill and those that are employed are in fear of losing their jobs and as a result have been impaired and in many instances the wage earner, even though employed, is unable to meet his obligations."

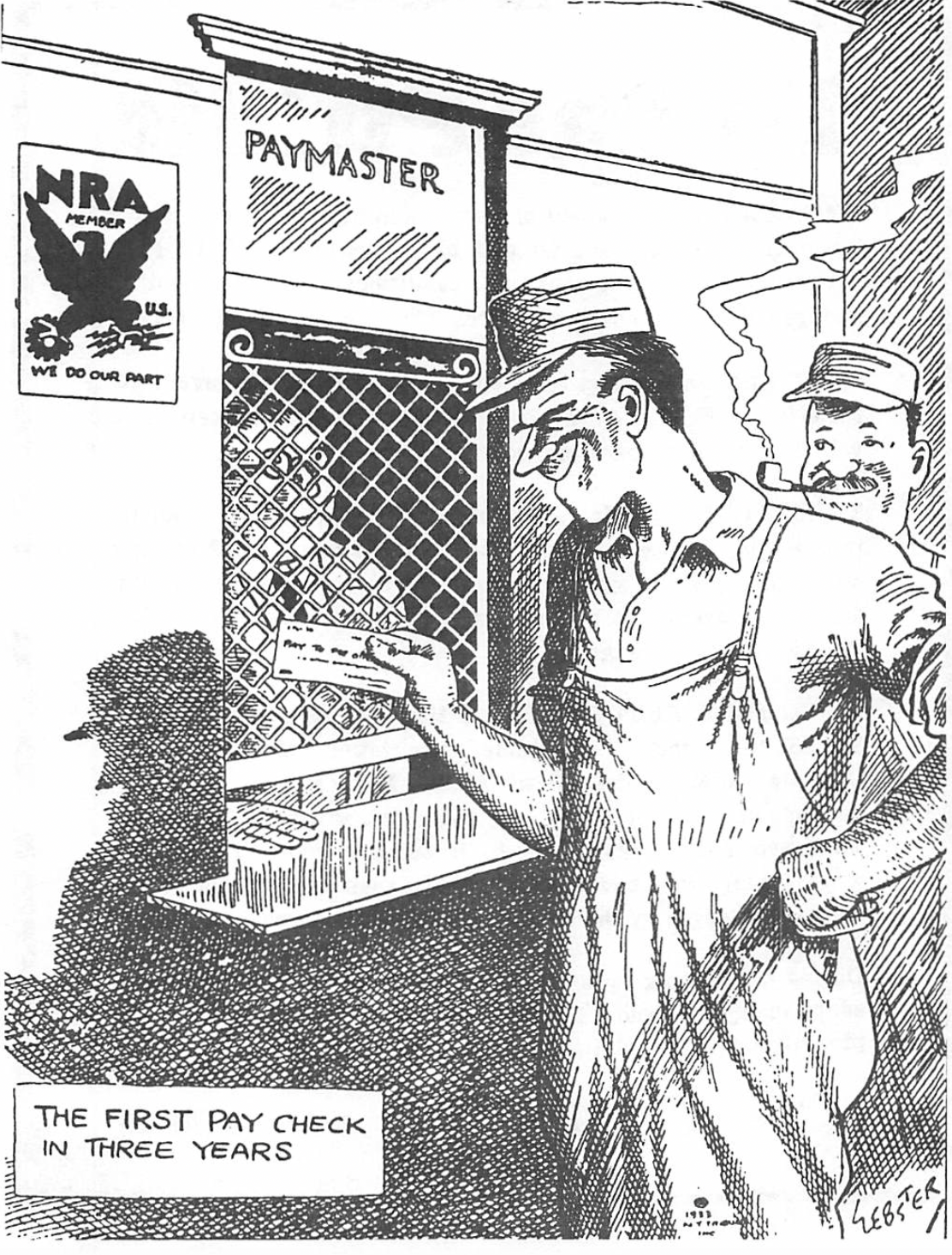

The election of Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1933 raised hopes in the depths of the Depression, especially after the passage of his 1933 National Industrial Recovery Act (NRA), which created the National Recovery Administration that sought to establish cooperation between business, labor and government in certain industries. The reforms sought to reduce overproduction and the work week to 40 hours, raise wages and guarantee the right of workers to form unions for the first time. However, the NRA panels were dominated by employers and the codes were largely unenforced. As Jabar noted, businesses easily found a way around the codes by making the $14 a week minimum wage in the woolen industry the maximum wage and speeding up production by increasing workloads. In 1935, the US Supreme Court ruled the NRA law to be unconstitutional.

Despite its flaws, the NRA gave a green light to workers to improve their situations by organizing unions and demanding better wages and working conditions. United Textile Workers experienced dramatic growth following the passage of the NIRA, growing from 15,000 members in February, 1933 to 250,000 members by June, 1934. That year, the UTW hired Jabar as a paid organizer to help textile workers unionize all over the state. In those days, Jabar would go into a places like Old Town, meet a few workers and put an ad in the newspaper announcing a union meeting. Often, the union would advertise dances with local swing bands, public suppers and Labor Day field days to draw in crowds.

If Jabar got seven workers willing to sign up, he would collect one dollar each for dues and send their cards to the national union for a charter. However, in the days before the National Relations Act, the employer wasn’t required to recognize the union even if a majority of workers signed cards. If a grievance committee member approached the boss to discuss an issue on the shop floor and the boss refused, the union would have to decide how to handle it.

“If it was a very grievous matter then you could call a stoppage of work and use your economic strength for him to sit down and listen to you if you wanted his plant to run,” said Jabar. “In other words, the only way you could get the respect of the employers is you had to hurt him in the sense that he’s going to lose production or he’s going to lose some money.”

But because the government had no formal method for mediating labor disputes and labor laws were stacked against workers, strikes often ended in violence as police were sent out to break picket lines.

The Uprising of 1934 Hits Maine

The big test of strength for Maine’s union textile workers came in the summer 1934, when 4,000 Mainers joined 500,000 textile workers nationwide in what became known as the Uprising of ’34, the largest textile strike in US history. The overriding goal of the general strike, explained Jabar, was to protest how ineffective the NRA codes were at upholding the right to fair wages and the right to join a union.

Southern textile workers took the lead as strikes ripped through cotton mills from North Carolina and Tennessee all the way up to Maine. Local 1802 not only had strike ready locals in Waterville, but also Vassalboro, Oakland, Dexter, Lincoln, Skowhegan and Bridgton. Textil workers in Biddeford, Saco, Fairfield, Madison and Pittsfield also joined the strike.

The UTW deployed “flying squadrons” of union organizers who traveled by truck and on foot from mill to mill calling out workers, but the workers were often way ahead of them. Over 750 National Guard troops were called out to several mills towns, including Sangerville and Biddeford to quell the unrest. Maine State Police set up check points and stopped cars to look for labor agitators and break up pickets. Younger workers taunted the police, but no violence was reported. Outside the York Manufacturing Company gates in Saco, a man shouting “Strike, strike!” was detained by police and taken to the station for questioning. York Company officials who met with workers nearby were roundly jeered and booed.

Kennebec County was hit the hardest by the walk-outs with all of the worsted mills shut down. In Waterville, several women strikers burst into the Lockwood Manufacturing cotton mill and smashed out a half dozen windows while 250 of the mill’s workers joined the strike outside. The incident came to be known as the "Great Riot of Waterville," but Jabar dismissed it as an exaggeration. What happened, he explained during a 1969 interview, was that workers were picketing on the other side of the street from where the Lockwood mill stood when someone, likely a former worker, by the name of Picard from North Vassalboro hollered, "Let's get the scabs!"

Prior to that, what excited the people more than anything else that at first it was the local police - they brought in the State Troopers [who] had their riot guns and their tear gas guns...and when they saw them that incited the strikers more than the people," recounted Jabar. "They hollered “Go get em!” Then there was a rush into the plant and they chased the workers all over."

At the same time, a local cop shot tear gas fired tear gas into the crowd, but the wind blew it back in his face and "he got knocked out." That's when the Waterville Mayor called in the militia.

"And that was the only day that we had riots," said Jabar. "What riots? There was no such thing as a riot. It was the way he picked it apart. It last only ten or fifteen minutes."

About 800 people, including 250 strikers, packed into a union hall in Madison where Jabar, now President of the Maine Textile Council, told workers to put aside their differences and unite. He told the crowd that the “three big enemies of strikers are the communist, the capitalist, and the fellow worker who becomes a scab.”

Over in Oakland, J.B. Tobin, president of the Oakland Textile Union, said workers there had no complaints about their employer but joined the national strike in solidarity with other workers to end what he called “cut throat” competition. The Oakland selectmen refused public assistance to strikers. Jabar condemned the decision and appealed to Democratic Governor Louis Brann for state or federal aid for striking workers.

“We won’t let anyone in Maine starve, strikers or not,” a state Emergency Relief Administration spokesman responded to a reporter.

However, management had prepared well and stockpiled inventory to weather the storm. With the help of police and the national guard, they crushed the strike. Some workers were murdered and thousands were blacklisted, chilling union activity in the South for generations. A 1995 documentary “Uprising of ’34” tells the story of the General Strike of 1934 and the workers who sacrificed everything for dignity and the American Dream.

But within a year, two major developments would change the course of the US labor movement for the better — passage of the National Relations Act and the rise of the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO). The NLRA, better known as the Wagner Act, created a formal system to guarantee the right of private sector employees to organize into unions, engage in collective bargaining, and take collective action such as striking. With much stronger labor laws and an improved climate for organization, Jabar would go on to lead Maine’s CIO with 80,000 members strong, representing workers in textiles, newspapers, shipbuilding at the height of World World War II.