Maine Photographer Documents Workers in America’s Vanishing Traditional Industries

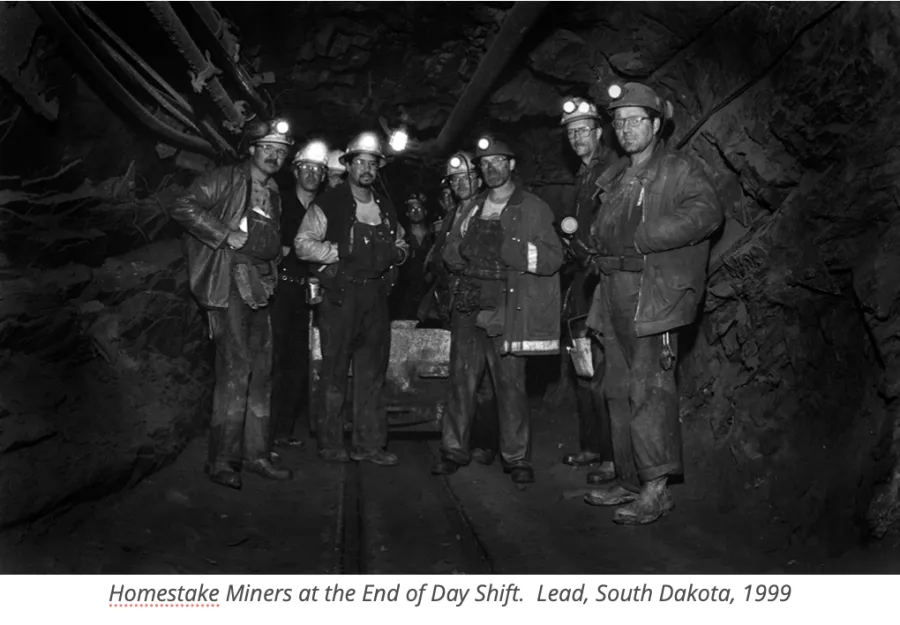

PHOTO: Homestake Miners at the End of Day Shift. Lead, South Dakota, 1999. Courtesy of Guy Saldanha

Ever since he was a little boy, photographer Guy Saldanha of Harpswell has been fascinated with the archeology of industry and the lives of workers whose backbreaking labor powers the nation’s industrial output. On car trips as a child with his family he would gaze out the window, wondering what the large warehouse stored, who built the old fieldstone wall and what goes on in the factory.

“When we were traveling to a city I was attracted oddly enough by smoke,” said Saldanha. “I was like ‘what’s going on over there? Who is working there?”

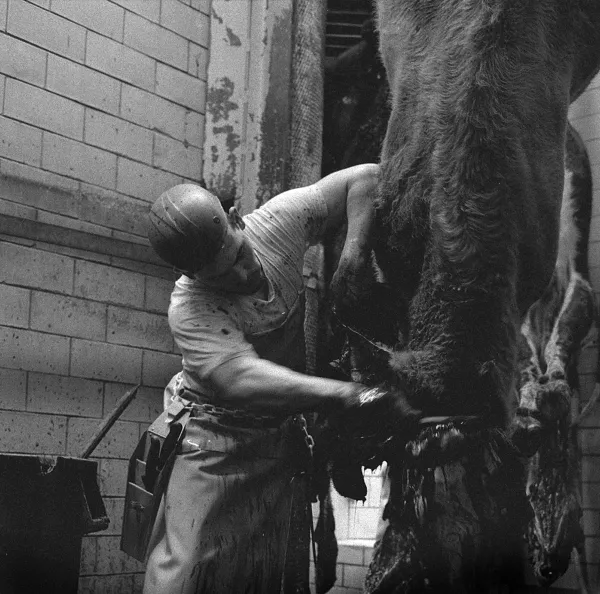

Eventually, while working at the Bowdoin College library in his late 20s in the late 1980s, he finally set out on his life dream of photographing working people in the nation’s traditional industries like farming, manufacturing and natural resource extraction. Saldanha’s work focused specifically on industries that defined and supported working class communities such as the steel industry in Pennsylvania, glass making in Indiana, New England textiles and shoes, Baltimore machine shops, Appalachian coal mining and Chicago meatpacking and railroads. He was specifically interested in industries that predominated between 1900 and the late 1920s and were recapitalized and still running with traditional manual labor.

While he wasn’t paid for his work, Bowdoin was generous with vacations, so he set out on several trips from the late 80s to the early 2000s, often for several weeks at a time. He slept in the back of his jeep as he hopped from mills and mines and oil rigs to slaughterhouses, rail shops and old growth forests. He was particularly interested in historically significant heavy industries like steel and mining where major strikes and labor struggles broke out in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Saldanha said he wanted to get to know workers and see if they were in anyway related to the people who did the same work a hundred years ago.

“Are they descendants, are they New Americans? How has the land changed in that area,” said Saldanha. “I wanted to know what it was like to be in a railroad tower to pull a pistol grip, to change the interlocking. What was it like to operate a draper loom, retying hundreds of threads when they broke? I focused on people’s faces and what their hands were doing.”

At the time he started his project, all of these companies were American owned, but many of these legacy industries were rapidly disappearing due to corporate mergers and offshoring. He knew he had to act quickly. He began his work before the internet was widely used, so he had to scour Standard & Poors books for contact information for the companies and carefully composed letters explaining his project and requesting entrance into the properties.

Some companies, like Maine’s paper mills, refused him entry, citing concerns about safety, liability and potential labor agitation. But he developed a strong pro-business pitch, stating that he wanted to tell the history of the company and how important it was to the community. He managed to get permission to visit 60 percent of worksites he requested to enter.

Visiting Farmers

Some of the first workers Saldanha visited were farmers. Typically his strategy was to park his car on the side of the road and approach farmers in the field on foot. One October day, while driving through Kentucky, he saw a family harvesting tobacco. Upon approaching the farmer, he asked if he could take some photos and offered to help with harvest. They wanted to get the crop in before the rain so they graciously accepted his offer.

“It was a great example of how I would like to be able to photograph, to be able to give something to the people I’m photographing in exchange for the opportunity to take their pictures,” he said. “That of course was really hard in an industrial setting.”

While on his way to visit an oil rig in Texas, Saldanha happened to be driving past a sugar mill in Raceland, Louisiana and was immediately intrigued. The owner turned out to be very friendly and let him right in to take photos.

Maine Shoes and Textiles

Saldanha was fortunately able to visit a number of shoe shops and textile mills in Maine while they were still running in the 1990s. He took photos of workers the Pepperell Mill in Biddeford, the Bates Mill and Quinco Fabrics in Lewiston, Falcon Shoe in Lewiston and Crow Rope in Warren. All of those factories have since shuttered.

“I was principally interested in the original location [of the mills]” said Saldanha. “And of course the equipment and the trades had gradually evolved as well. It wasn’t that I was trying to show something nostalgic consciously. I think I was trying to show the recapitalization of these original industries and the people who worked in them in the present.”

Both Bates and Pepperell have a long storied history in Maine as they led to the development of both cities as working class immigrant communities. Bates notably was the site of one of the first textile strikes in Maine in 1854 when women workers “turned out” for a shorter work day.

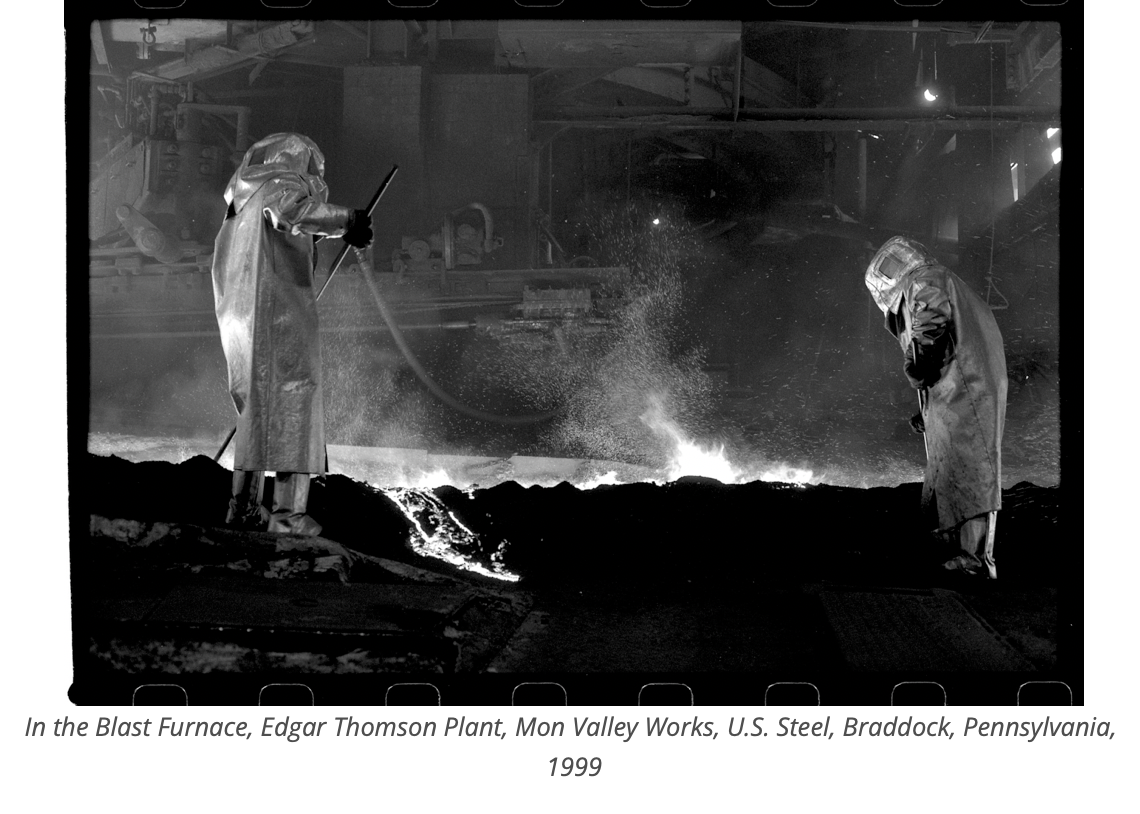

Steel

Saldanha was especially excited to visit the Edgar Thomson Steel Works in Braddock, Pennsylvania. Still running, it is an original Carnegie Mill built in the 1870s and one of the oldest steel mills in the country. Before the mill was built, it was the spot where rebel militia men and farmers rallied during the Whiskey Rebellion in the 1790s. A hundred years later, workers with the Amalgamated Association of Iron and Steel Workers battled armed Pinkerton strikebreakers in the Homestead Strike, leaving nine union workers and seven guards dead. Infuriated by the massacre, anarchist Emma Goldman's lover Alexander Berkman later attempted to assassinate the mill manager Henry Clay Fricke. Berkman spent 14 years in prison for the crime.

Saldanha wanted to explore the mill not just for its historical significance, but also so he could see the carbon steel process and the facilities blast furnaces. He also visited the Republic Steel Plant, site of the 1937 Little Steel Strike when members of the CIO’s Steel Workers Organizing Committee staged sit-ins and picket lines. Known as one of the most violent strikes of the 1930s, thousands of strikers were arrested, 300 were injured and eighteen were killed.

The Railroad Shops

Saldanha was ceaselessly amazed at the deep, dark cavernous rail shops where various trades people worked on the nation’s rail fleets. In many of worksites he was accompanied by a public relations specialist or a safety person, but the superintendent at a Topeka, Kansas rail facility let him roam free. He simply instructed him to be there at 6pm, brief the men on what he was doing and avoid stepping on the rail.

“In those days there was a huge amount of pride in the railroad, though it’s taken a hit recently,” said Saldanha. “I loved that kind of community of people and I was fascinated by it.”

The workers in the shop were doing heavy rebuild work like taking apart traction motors and lifting entire body cabs off engines. Dozens of engines lined up outside waiting to be worked on in the massive facilities which ran three shifts, 24-7. Some of the shops dated back to the 1870s and 80s when steam locomotives were built.

Beginning in the 1970s and 80s there was a wave of rail road bankruptcies and at the time Saldanha was shooting, railroads were being deregulated and going through massive Wall Street mergers. Many of those companies like the Southern Pacific, Denver & Rio Grande Western railroads have since disappeared and several of the rail shops have closed and consolidated.

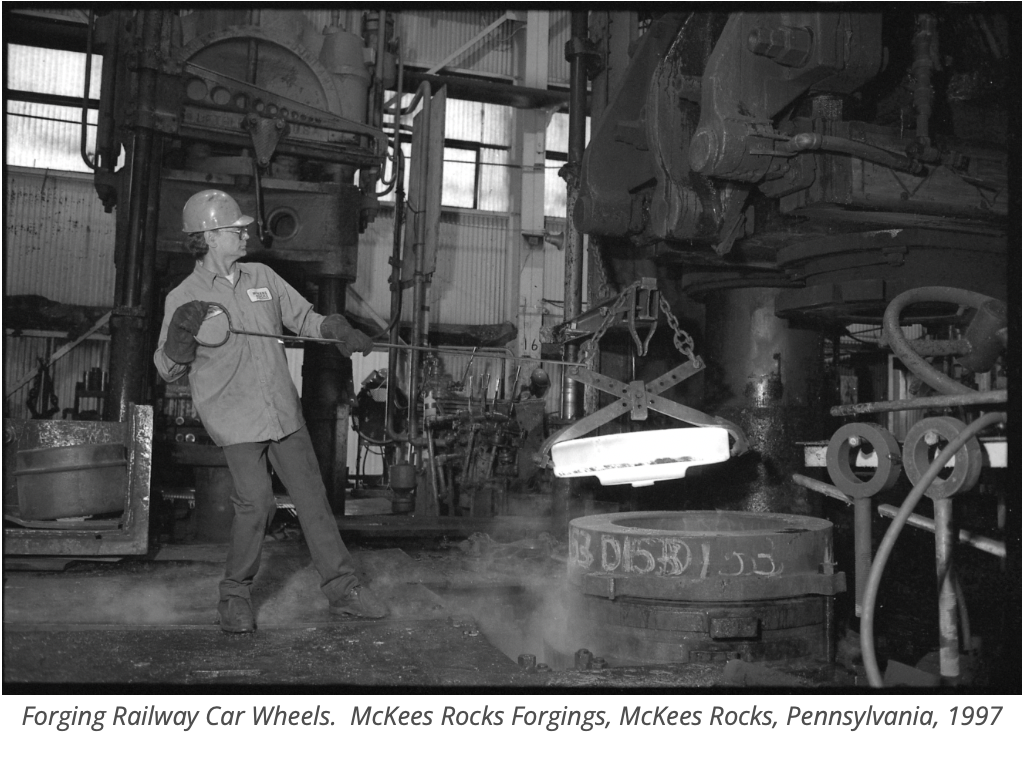

One of the highlights for Saldanha was visiting the Burlington Northern Santa Fe shop in McKee’s Rocks in Allegheny County, Western Pennsylvania because it was where major strikes occurred in 1877 and 1909.

Coal & Hardrock Mines

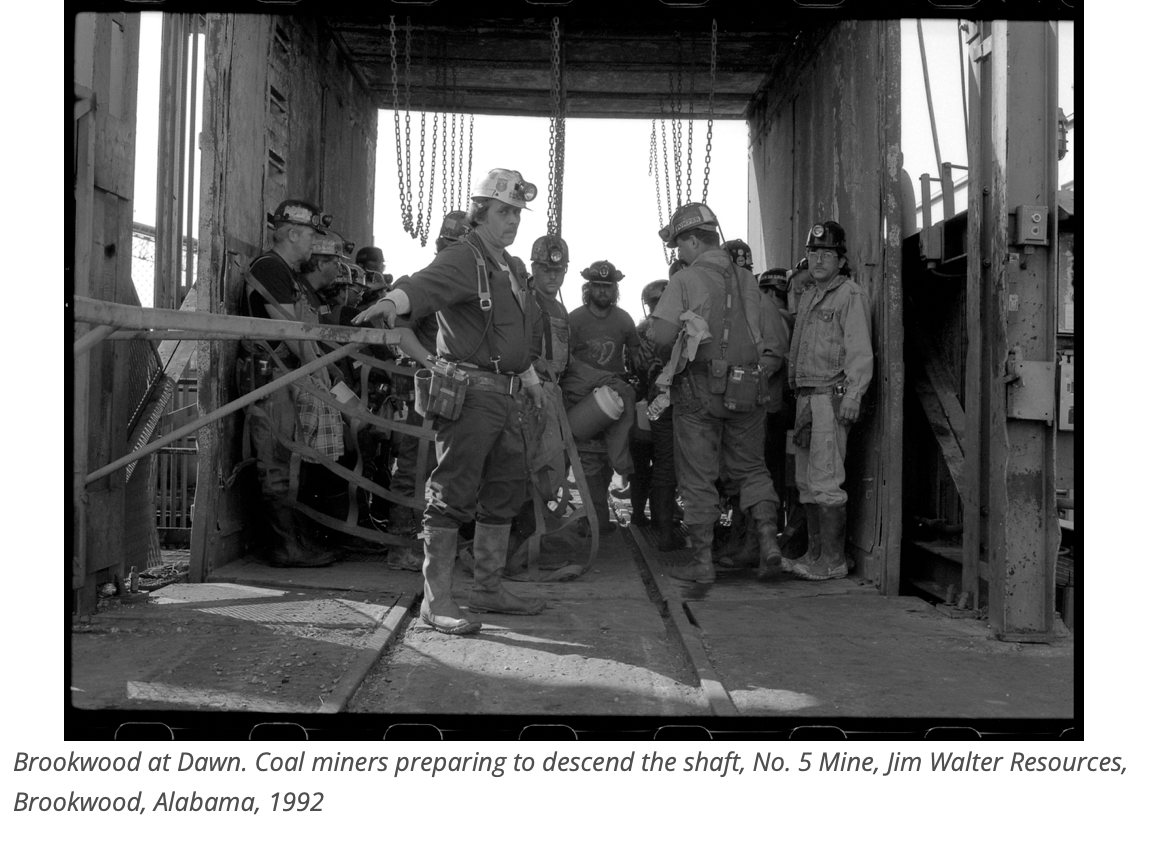

Some of Saldanha’s most visually striking photos were taken deep in the bowels of the earth in the coal mines of Appalachia and Western metallic mines. He tried to practice shooting photos in simulated, dark, enclosed places at home, but nothing prepared him for going 3,000 feet underground and photographing miners.

“In anthracite mines all you have is a little carbide light and people were moving,” said Saldanha. “I didn’t want them to pose or smile, I just wanted it to be an actual work scene. And I didn’t like it when things were set up for me. I wanted it to be natural.”

He was also very self conscious about being perceived as an “intruder” or putting workers at risk by interrupting their work so he avoided too much personal interaction with them and tried to just be a fly on the wall. In some places, like in South Appalachian coal mines, the companies only let him film outside the mine because they were concerned for his safety. The southern mines were very gassy and filled with methane. Nine years after he filmed workers at the Black Warrior Coal fields in Alabama there was an explosion that killed several miners in 2001.

In walking the streets of mining towns, Saldanha enjoyed speaking to retirees on their porches and in their yards about the old days. One early fall evening in 1989, he met a retired coal miner with black lung disease named "Shotgun" who was on his porch with his dog Brownie while supper was cooking.

“Retired people were usually outside, not kids or young people. I loved meeting people whose memories recalled an earlier time," he said.

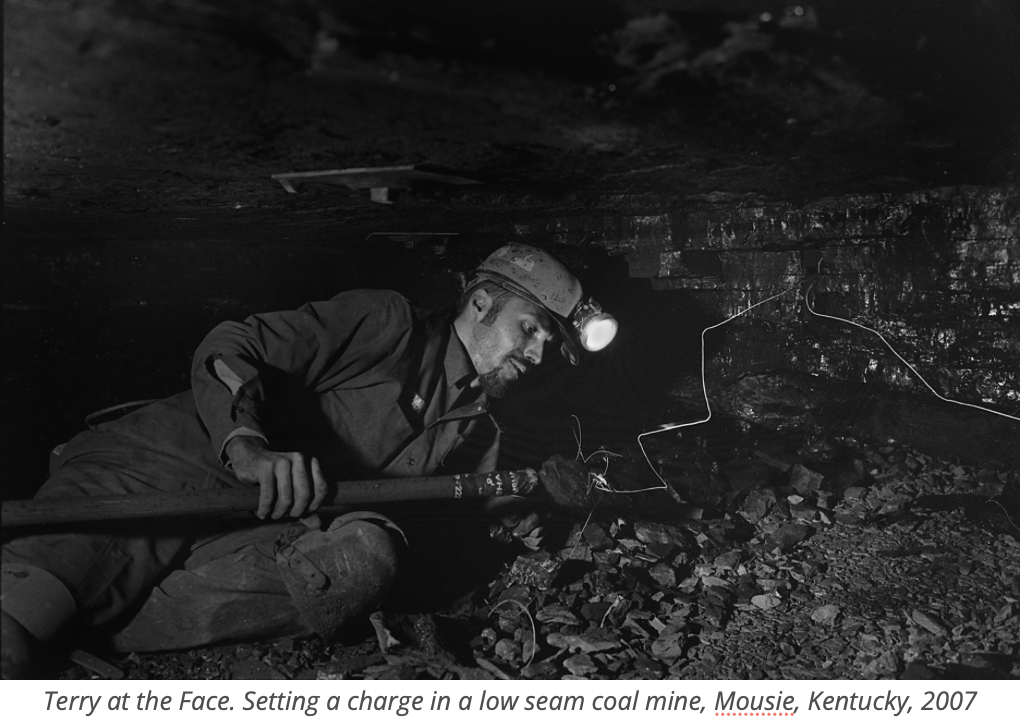

In Kentucky, Saldanha sought to get into low-seam mines, but said it was very difficult because people were suspicious of outsiders. On his last trip to Kentucky in 2007, a friend of one of the mine owners helped set up a mine visit for him, but gave him a chilling warning.

“He said, ‘You better be who you say you are because I don’t want to see you hanging from a tree,’"recalled Saldanha. “He was very kind to help, but he was just being very direct in warning me.”

In the pitch dark low seam mines, the roofs of the seam were typically only 35 inches high, so miners go into the mines on their backs in an electric buggy and work on their sides and crouch. In areas where there were aquifers, it was very wet and he had to protect his equipment from the constant dripping water.

Despite some safety improvements, mining can be very dangerous and it's estimated that 16 percent of coal workers develop black lung disease from inhaling coal dust. In most of the photos miners are not wearing the respiratory equipment provided. As Saldanha explained, the miners are supposed to wear it, but they don’t because it is so uncomfortable and they end up trading short-term comfort for long term health.

“The younger ones are usually more sensible and will have their hearing protection and glasses and their breathing masks but wearing that kind of equipment all day long is really uncomfortable,” he said. “Your lips get blistered and your glasses fog up. I think the companies were aware that this kind of stuff was going on and they just kind of ignored it.”

He said he was was upfront with the companies that he was not trying to “expose” any wrongdoing and always sent proof sheet to make sure they didn’t have any concerns about the photos.

In Northern Idaho Saldanha visited hard rock mines where some of the biggest labor struggles occurred with members of the militant Western Federation of Miners and the radical Industrial Workers of the World.

Oil Rigs, Meatpacking & Logging

On the oil rigs of West Texas, Saldanha was able to be alone with five-person crews as they drilled for oil. The crew consisted of a driller, chain hands and a couple deckhands. A rig manager known as a “toolpusher” lived on site and the roughnecks worked around the clock for four days in a row until their next break. He formed a friendship with a woman named Saralie, the only woman on one of the crews.

“I was fascinated by her work because she was surrounded by men in the most macho industrial occupation you can be in,” said Saldanha. “There were no facilities for women at all. They’d basically have to change behind the trailer and go to the bathroom there. She got a lot of flak, taking verbal abuse from the men all the time.”

These days, Saldanha is focused on other endeavors, but he does have one last photography project as part of this series in the Western Pennsylvania anthracite coal mines.

“I’m very interested in Western Pennsylvania and the anthracite mines because it’s like the crucible of the Industrial Revolution in this country,” he said.