Maine Labor History: Modern Unions Organize at Portsmouth Naval Shipyard

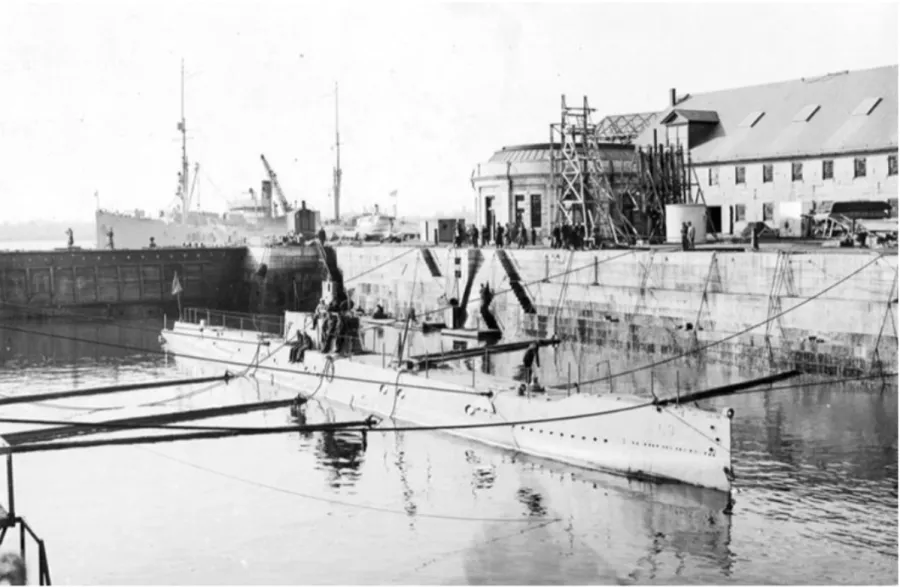

PHOTO: USS L-8 (Submarine # 48) In dry dock at the Portsmouth Navy Yard, Kittery, in 1917.

This is the second installment of our history of workers' struggles at the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard. Read our first part: Portsmouth Naval Shipyard Workers: More than 225 Years of Struggle for Dignity, Fair Wages & Workers’ Rights.

Portsmouth Naval Shipyard workers began organizing their first modern unions in the early 1900s. One of the earliest locals formed there was the International Brotherhood of Boilermakers, Iron Shipbuilders, Welders and Helpers of America Local 467 in 1906. The “fightin' Machinists” organized their own union in 1913.

During World War I, the shipyard workforce grew to 5,000 civilian workers overhauling and repairing surface vessels and building the first submarines like the diesel-powered L-8 subs. On January 12, 1918, about 30 mechanics from the shipyard met at the local Oddfellows Hall to form a Metal Trades Union of the American Federation of Labor. It encompassed several trades including the blacksmiths, boilermakers, electrical workers, engineers, machinists, metal polishers, molders, pattern makers, plumbers, sheet metal workers and stove mounters. In the Portsmouth Herald, the founders of the union argued that the organization would be “broader in scope” than any single union and would be “more genuinely helpful to all men in the metal trades, than a single union could be.”

Chartered in 1908, the Metal Trades Department was established by the AFL to coordinate negotiating, organizing and legislative efforts of affiliated metalworking and related crafts and trade unions. Its primary jurisdiction in New England covered private and federal skilled craft workers in shipbuilding and related maritime ventures. It represented government navy yards and war work plants, including tradesmen at shipyards in Portsmouth, Bath and Rockland, which were booming with wartime production. However, only the Portsmouth Metal Trades Council survived out of the three Maine unions.

As the Portsmouth Metal Trades Union stated in a news release, its mission was “to promote harmony between the various locals and to aid weak unions by giving them the chance to affiliate with an organization that is national in scope and also in small places where only a few men of each trade are employed.”

The first elected President of the Metal Trades Union was a 35-year old machinist named Harry L. Hartford, who lived in York, Maine with his family at the time. Leadership also included Secretary and Boilermaker Ed J. Clark and organizing committee members Fred S. Pray, chairman, Pattern Maker; W. T. Burrows, Sheet Metal worker; George A. Cates, Pipe Fitter and Plumber. That same year, the International Federation of Professional and Technical Engineers (IFPTE) Local 4 was formed at the yard.

Establishing the Metal Trades Council Cooperative Store

At the Metal Trades' second meeting on February, 21, 1918, a large audience came to see a number of guest speakers discussing “the solution of the greatest problems that confront organized labor today.” At the time, wartime inflation had accelerated with prices shooting up more than 80 percent between December 1916 to June 1920. The council’s meeting was aimed at informing the public about "the way to get a maximum wage and to pay the minimum price for the necessities of life.”

The first speaker of the evening was Mrs. Creel of New York, a member of the Executive Council of the Co-operative Society of America, who gave a lecture on the role cooperatives could play in addressing soaring prices.

“Unless organized labor can regulate the prices of commodities that constitute the necessities of life, of what benefit are the wage wars that the unions are conducting all over the country at present time, and where will the fight benefit them unless they can dictate the prices they shall pay as well as the wages they shall receive,” she asked, according to the Portsmouth Herald.

She then proceeded to outline a plan to create a cooperative store. It certainly wasn’t a new idea. Workers in Maine and New England had been experimenting with cooperatives beginning in the 1840s and the idea typically gained steam during times of economic crisis. Creel argued that cooperative stores started in England seventy-five years earlier with $140 in capital were distributing nearly $1 million worth of commodities to their members annually and distributing substantial dividends back to members. The meeting ended with a social dance accompanied by a pleasant concert by Hecker’s Orchestra.

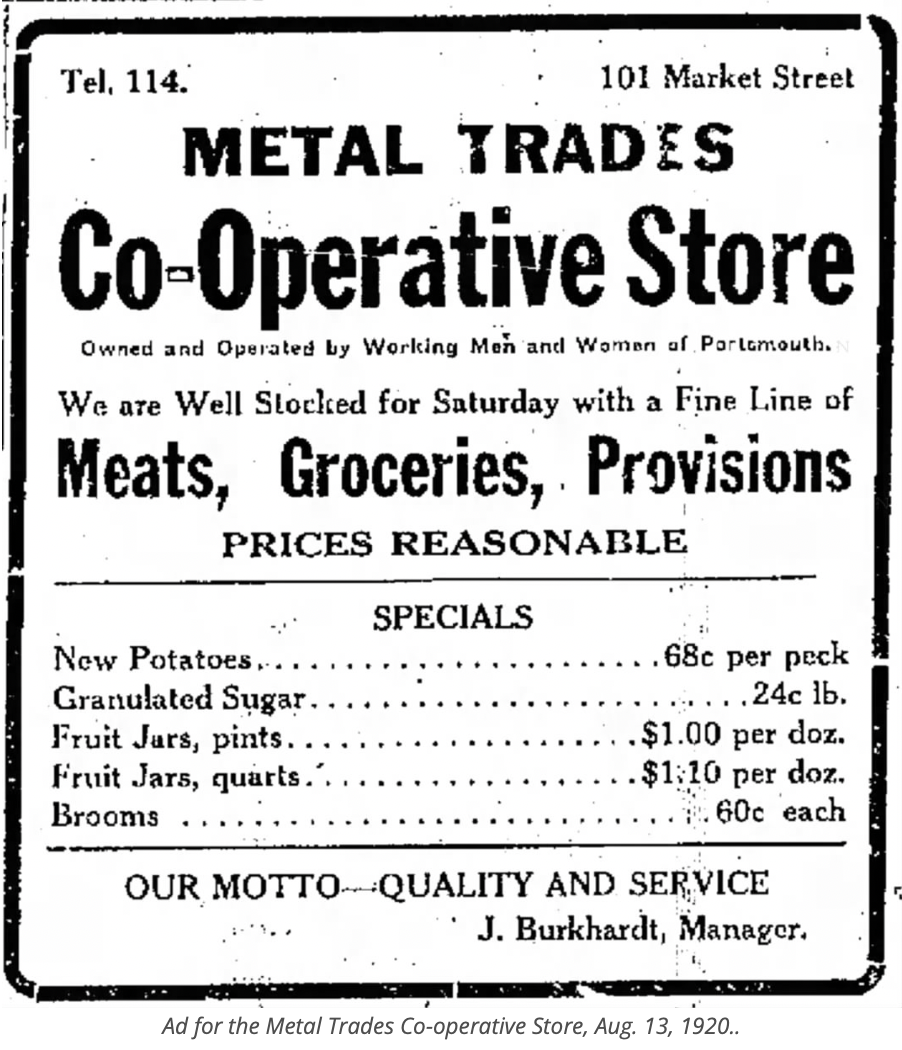

Later that spring, the union’s Metal Trades Cooperative Association established a cooperative store on Market Street in downtown Portsmouth with $30,000 in capital stock. The store advertised a wide variety of meats and even a delivery service. It also joined several businesses in a half-day closure in solidarity with “overworked grocery men” seeking fair treatment that fall. In 1920 the Metal Trades advertised that anyone who purchased $10 in stock would receive a 5 percent discount at the store. But a few months later the union shuttered the store and Rockingham Market opened up in its place.

Despite that setback, the Metal Trades continued to thrive, hosting dances, concerts, carnivals, suppers and charity events. They held a field day and had a float in the town’s Patriotic Parade and Flag Raising on the 4th of July, 1918. They also offered their support to other workers including their brothers with the Charleston Metal Trades Council at the Boston Navy Yard who were fighting for better wages.

The Metal Trades also sponsored a lecture by United Mine Workers organizer John W. Brown to discuss the struggles of coal miners out west. A Bath Iron Works joiner and union organizer, Brown was involved in some of the most violent and bloody labor struggles in US history, including the Ludlow Massacre when Colorado National Guard and private guards employed by the Colorado Fuel and Iron Company murdered 21 people, including miners' wives and children. Brown went on to organize the first Industrial Union of Marine and Shipbuilding Workers of America (IUMSWA), CIO union at BIW in 1934.

Adopting the Progressive Nonpartisan League of Maine Platform

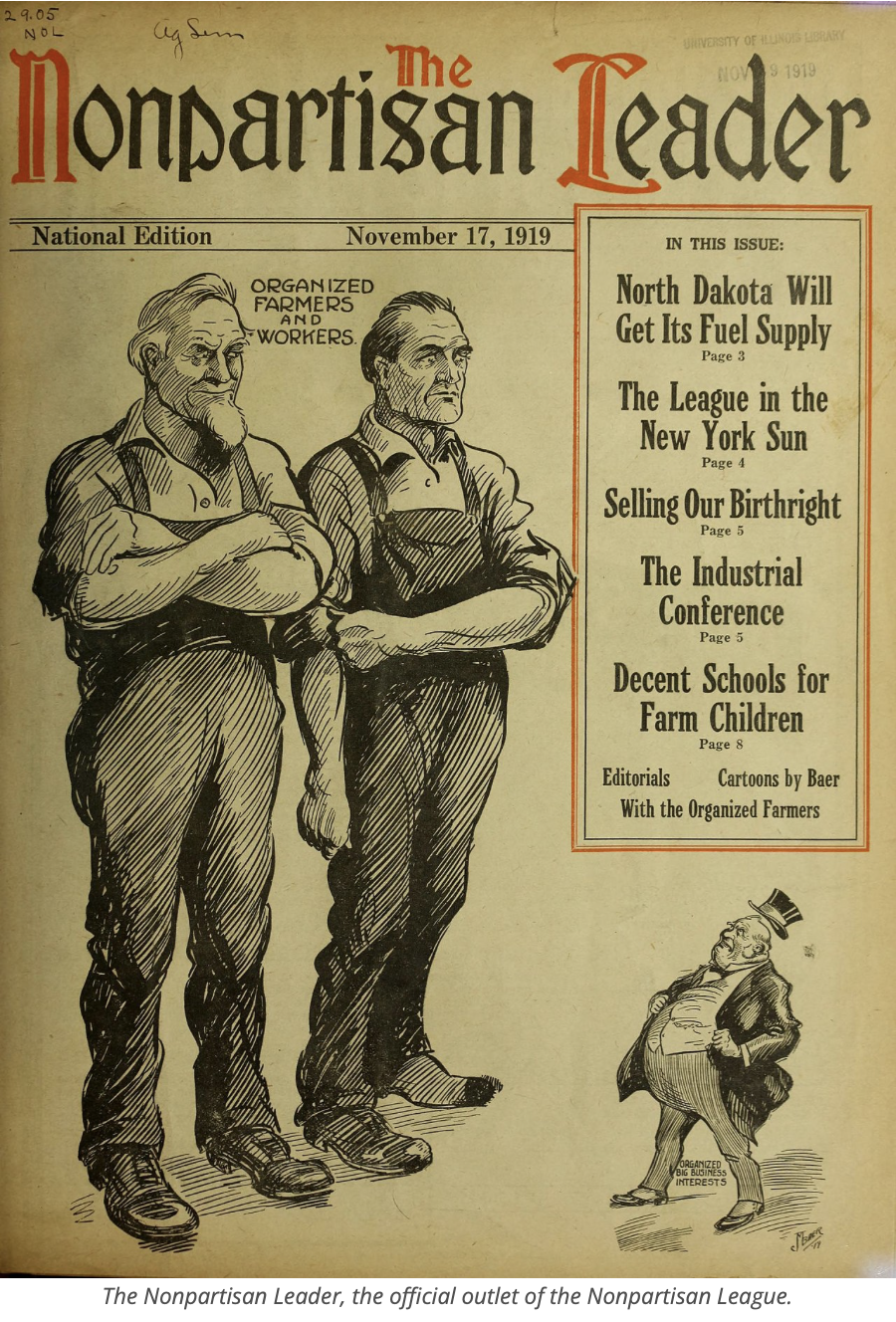

The Metal Trades Union was quite politically progressive for its time and at its third meeting in March, it adopted the platform of the Non-Partisan League of Maine, a third party with origins in North Dakota that had recently formed in the labor stronghold of Rockland, Me.

The platform called for a national citizen initiative, recall and referendum process; government ownership and operation of public utilities like railroads, coal, iron, and copper mines, telegraph, telephone and water powers. It supported empowering the government to regulate prices by establishing publicly run grain elevators, stockyards, storage warehouses, flour mills, fuel yards and other means of distribution. The platform called for a more progressive tax system, limits on war profiteering, the right to organize unions and legislation to improve wages.

The Metal Trades members were clearly fed up with the tremendous bloodshed and suffering caused by the Great War and advocated for the “adoption of the Swiss democratic military system, instead of a large standing army.”

“We believe that as soon as this war closes, this country should enter into treaties with other countries for disarmament and the settlement of all differences by an international tribunal,” the platform concluded.

As happened in previous wars, the workforce at Portsmouth Naval Shipyard was sharply cut after World I with the scaling down of wartime production.

It would be forty years before federal civilian workers were granted collective bargaining rights, so they focused on exerting political pressure on the Navy to raise wages and improve working conditions. With a steep rise in the cost of living, shipyard workers were not satisfied with the Wage Board’s 5 percent wage increase in 1920. The Metal Trades urged the Secretary of the Navy to consider a higher wage adjustment. But, the Navy refused to approve more funding for raises unless they were unaccompanied by workforce reductions.

In 1923, the Metal Trades joined workers at other shipyards in protesting cuts in their pay. The Portsmouth Herald reported that there were "hints of walk outs and strike by some," but "the rank and file will proceed in a quiet and orderly way in setting forth their grievances.”

Fighting for a Better Pension System

Shipyard workers were also focused on winning retirement pensions, which was a benefit few workers had in those days. Between 1900 and 1930, average life spans increased by ten years, the most rapid increase in recorded human history. At the same time, fewer and fewer people lived on farms in extended families as many left rural towns to make a living selling their labor in more industrialized regions of the country. Without the traditional family safety net, millions more elderly Americans were struggling in poverty.

The Civil Service Retirement Act, which became effective on August 1, 1920, established the first universal retirement system for federal employees, granting retirement, disability, and survivor benefits. Under CSRS, employees qualified for a pension after reaching age 70 and completing 15 years of service. Mechanics, letter carriers and postal clerks were eligible at age 65, and railway clerks qualified at 62. The annuities were determined by length or service and salaries. $720 was the maximum annuity and $180 was the minimum.

Part of the reason Congress passed the CSRA was to allow older federal employees to retire to make more positions available for returning veterans. Prior to World War I, only disabled veterans were given preference in hiring for federal jobs. The Census Act of 1919 gave preference in hiring to all honorably discharged veterans and their widows. Over the years, Congress has made several improvements to this program, resulting in veterans today making up nearly 30 percent of the federal workforce. When the CSRA took effect, thousands of federal workers immediately retired, some of whom were over 90 years old.

Unfortunately, many federal workers found that their pensions did not adequately cover their living expenses. In November, 2020, the Portsmouth Metal Trades Council issued a call to organize a Branch of the New England Civil Service Retirement League, bringing together postal workers, tax office employees, railway mail clerks and Navy Yard shipbuilders to advocate for strengthening their pension plan. The organization called on Congress to make their pensions based on service rather than age, ensure timely monthly payments and that workers received a straight percentage of their earnings as retirement compensation. The group argued that workers shouldn’t have to foot the whole cost of the pension and sought to have a voice in how their money was invested.

The Metal Trades Council joined other groups like the Association of Retired Federal Employees (now the National Active and Retired Federal Employees Association) throughout the 1920s in supporting legislation that reformed the CSRA and fixed inequities in the law. A 1926 law raised the amount of the annuities retirees received but also increased the amount deducted from the wages of current employees from 2.5 percent to 3.5 percent of their salaries.

The Metal Trades Council and Electoral Politics

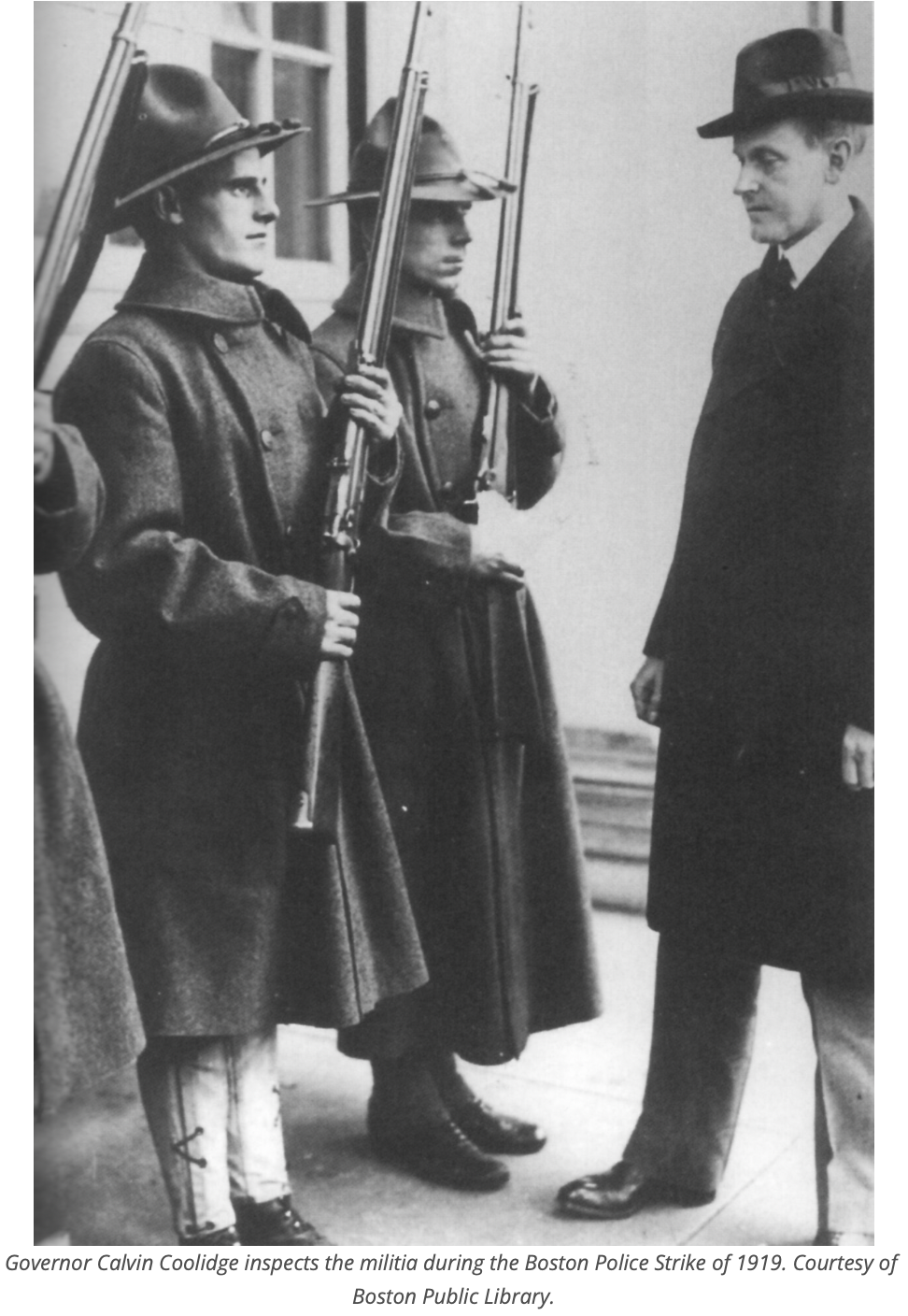

Metal Trades Council leaders despised Massachusetts Republican Governor Calvin Coolidge, especially after he called out the National Guard to violently put down the Boston Policeman’s Strike of 1919, fatally shooting nine civilians in the process. Portsmouth MTC President Harry L. Hartford was among the speakers at a meeting of the Quincy Metal Trades Council the following month that the Boston Globe described as an “anti-Coolidge rally.”

When Coolidge was nominated to be Republican Warren Harding’s running mate in the 1920 election, the Metal Trades Council rallied behind Ohio Democratic Governor James M. Cox and his running mate Franklin D. Roosevelt. As governor, Cox passed a no-fault workers' compensation system and restricted child labor. If elected President, he promised to pass legislation to finally give workers collective bargaining rights.

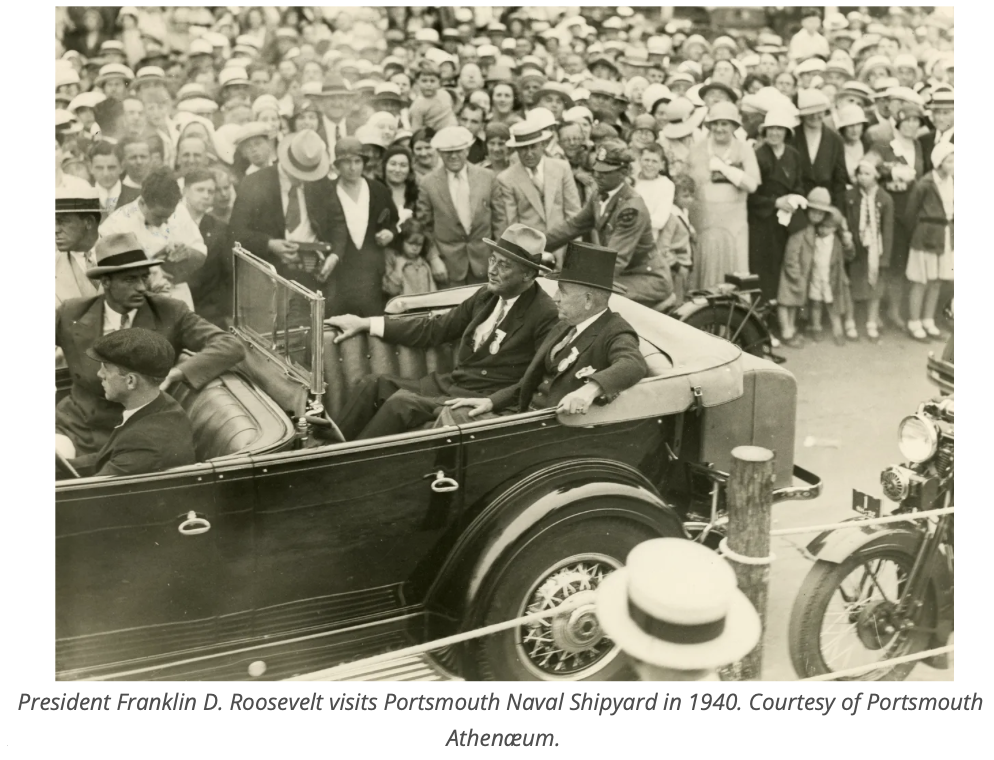

The Portsmouth Metal Trades Council especially adored FDR, who had been very supportive of workers as President Woodrow Wilson’s Assistant Secretary of the Navy. On September 13,1920, the Metal Trades held a rally for Roosevelt at the Portsmouth Theatre.

“Mr. Roosevelt has always been a great favorite with the workmen at the at the navy yard,” the Portsmouth Herald reported, “and while he was in office no expression of good will could be made for any more substantial manner than by word or letter, but once out of the navy and a private citizen the workmen of the yard seized the opportunity of his being here to show him how they appreciated his good work in their behalf.”

The new Metal Trades President F.A. Staten and a delegation from the yard presented FDR with a “handsome solid gold watch” and the union collected contributions for his campaign from members. In a brief speech, Roosevelt recalled the courtesies that the shipbuilders had always shown him and said he planned to keep the watch as a cherished keepsake for one of his four sons. No matter what the outcome of the election, he said he hoped to keep in touch with the navy yard workmen. The Democrats ultimately lost that election, but FDR made a big comeback over a decade later in the depths of the Great Depression. True to his word, he delivered for the shipyard workers.

At a meeting in January,1936, the Portsmouth Metal Trades Council celebrated several key labor reforms signed by President Roosevelt including the Fair Labor Standards Act, establishing overtime and the 40-hour work week as well as new laws that brought more work to the yard, often at the expense of private shipyards. Unfortunately, federal workers were excluded from collective bargaining rights in the 1935 National Relations Act, but they would continue to fight on through the 1940s and 50s to gain that cherished right.

By that time, the American Federation of Government Employees had established itself at the shipyard with the founding of AFGE Local 130 with 57 members in 1932. The Metal Trades continued to lend its solidarity to other workers, including calling on the City of Portsmouth to raise salaries for woefully underpaid public school teachers in 1944. The Metal Trades also opposed foreign guest worker programs. When New Hampshire's farm labor supervisor announced that he had applied to the federal government to bring in foreign farm labor, the Metal Trades warned that they would take jobs from returning veterans.

“We have no quarrel with the duly registered aliens who are admitted to this country on a permanent basis,” said Metal Trades Council President John R. Pennington in a Portsmouth Herald article dated Jan. 29, 1946, “but we feel that Americans who have turned to the service and to the ship in time of need should be allowed sufficient time to reenter the farm field.”

Organizing & Fighting for the Shipyard's Survival in the Nuclear Era

During World War II, the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard workforce grew to a whopping 25,000 workers constructing over 70 submarines, with four launched every single day to fight the fascists in Europe and the Japanese in the South Pacific. By the end of the war, the yard had become the primary hub for submarine design and development. But the yard also had to dramatically scale down its workforce.

In August, 1949, Ralph Henry, Vice President of the Eastern Seaboard group and President of the Metal Trades Council at the Brooklyn Navy Yard, offered a stern warning to workers that the shipyard was in danger of being completely shutdown. Speaking to a small group of about 25 workers at the Metal Trades union hall on Market Street, he said he learned personally from the Secretary of the Navy that he was planning to cut Navy shipyards by a third, hitting smaller yards like Portsmouth the hardest.

“The ax might fall in a matter of weeks,” Henry warned. “We can’t survive just sitting around waiting for the funeral. We must attempt to obtain other types of work from other government agencies."

Henry told the shipyard workers that Portsmouth was facing stiff competition from private shipyards because they were politically more powerful as they were all heavily unionized. Private shipyard unions were much stronger than their federal counterparts because they had collective bargaining rights and had closed shops. They had union security clauses in their contracts that ensured all workers in a bargaining unit contributed for the cost of collective bargaining.

Henry explained that Secretary Louis Johnson had relegated the Navy department to “the bottom of the totem pole” because defense “bigwigs” believed that a future war will be fought and won by “bombers, more bombers and still more bombers.” Henry explained that the East Coast Metal Trades were backing a proposal to transition the yard to production in the emerging atomic energy sector, but it needed the support of the Portsmouth shipyard workers.

"After all, what difference does it make if you are producing items for the Atomic Energy Commission as long as your pay check is received every week?” he said. “You can’t survive here on tradition. If you lose your jobs now, you will never return to work at the Portsmouth yard. If you think anything of your employment — of your security, — you must get the entire town behind you. Write yourselves and have everyone else write personal letters to your senators, representatives, the secretary of defense, the chief of the Navy Bureau of Ships and to any other person or organization that can help you.”

He added that naval officials who used to oppose unions were finally supporting unions, but workers needed to step up their organizing efforts.

“You need immediate strength and financial support,” he warned. “Organize and set up a ‘job insurance’ fund. It’s your only way of fighting for your jobs.”

One of the union leaders complained about the lack of attendance at the meeting, attributing it to “laziness, a false sense of security and ignorance of the facts” on the part of a large majority of shipyard workers. A Metal Trades official told the Portsmouth Herald that attempts to organize the shipyard had ended in failure because of “lack of interest and fear of reprisal by the masters or naval officers.” Still, the workers who did attend the meeting came away "keyed to a high pitch of Henry’s dark predictions and vowing that they’d start an immediate campaign for organization."

By 1950, Portsmouth Naval Shipyard's workforce had sharply declined to 4100 workers. But the shipyard also continued to innovate. In 1953, it pioneered the teardrop hull and round cross-section design of the research ship USS Albacore, which is now on display at Albacore Park, a National Historic Landmark site located in Portsmouth. Four years later, in 1957, Portsmouth Naval Shipyard workers completed the Swordfish, the first nuclear-powered submarine built at the base. The last submarine built here was Sand Lance, launched in 1969. Nevertheless, the Metal Trades Council would continue to have to fight against other proposed closures into the 21st Century.

Next week: When Portsmouth Naval Shipyard workers finally won collective bargaining rights.