Maine Author Monica Wood Discusses Solidarity & the HarperCollins Strike

HarperCollins Union members last week ratified a new contract after a three-month strike against HarperCollins Publishers, a subsidiary of the media giant News Corp. Members returned to work on Tuesday.

“We are very proud of this agreement. Our members fought tooth and nail for every letter of it and the result goes beyond the many improvements we’ve won in this contract,” said Olga Brudastova, President of UAW Local 2110, in a statement. “I am confident this will lead to a long-lasting change in work culture at HarperCollins and perhaps in publishing at large.”

Bestselling Maine author Monica Wood was an outspoken supporter of the HarperCollins workers and even refused to sign off on the cover of her latest novel in solidarity with them. The risky decision delayed the release of her new book “How to Read a Book” for another year and could have forced her to return her advance payment.

Wood grew up in a union household. Both her father and grandfather worked for the Oxford Paper Company in Rumford. Her brother Barry Wood, who passed away last year, was briefly President of USW 900 when Boise Cascade owned the mill in the 1980s.

Wood spoke to the Maine AFL-CIO Maine Labor News on Thursday to discuss the strike and its outcome. Wood has vivid memories of worker struggles in the paper industry during the 1980s, especially in Rumford and Jay. From a young age, she was taught to never ever cross a picket line. She says the whole experience standing in solidarity with her beloved editors at HarperCollins has been emotionally challenging.

“Yesterday I had a long talk with my darling editor, who is so beyond thrilled to be back at work. She was just so happy,” Wood told Maine Labor News. “I kind of had to say, ‘nobody wins a strike. There are feelings that linger on both sides so just be prepared for that.’ I felt like a big old wet blanket, but it’s true. That does happen."

While it’s always exhilarating to publish a new book, Wood says the past three months sucked the joy out of her and it will be a while before she is able to regain that feeling. She is angry and disappointed not just with the company, but that there weren't more authors refusing to cross the picket line.

“I was so insulted when somebody asked my husband the question, ‘If it was her first book would she still do it?’" she said. "That’s like saying ‘if I give you a million dollars would you sleep with me?’ It’s like a price, right? I’m like ‘no.’"

For Wood, refusing to cross a picket line is not about being “virtuous,” but a deep seated value that cannot be negotiated.

“There was no ‘should I or shouldn’t I? What if they cancel my book, will I have to pay back my advance,' she added. “All of that stuff doesn’t matter. There are certain values that are rock solid.”

Part of the problem, Wood says, is that in some industries like publishing it’s easier to cross a picket line because you don’t have to physically cross it and look the workers in the eye. At one point during the strike Wood addressed other authors directly:

All my fellow authors, just imagine every time you had to do something like having a discussion with the marketing people, approving your book cover, or looking at the copy edit, you had to go into the building to do all those things. How would you feel? Maybe you’d have a different feeling about

who is on the sidewalk and why.

“It’s just so easy to ignore that when we’re all clicketty clacking from our home offices,” she added.

At the same time, Wood says she also feels a strong sense of optimism at seeing so many young people in traditionally non-unionized sectors standing up and taking collective action.

"I’m used to picket lines with the same types of people with certain types of clothes,” she said. “But at the HarperCollins strike, there were all of these cute young women in their little coats and boots, holding their coffee and puppy dogs. I was like ‘ok, alright, this is a new dawn, a new era. This is what solidarity now looks like.’ It was just so beautiful. They’re mad as hell and they’re not going to take it anymore.”

Wood compared the publishing industry to what happened to the paper industry in 1970s and 80s, when large Wall Street investment firms bought up all the mills to squeeze out more profits out of them at the expense of workers. When Wood was growing up, there were better relations between workers and management because they all knew each other and lived in the community. But when large faceless corporations came to town things changed for the worse.

In the past 25 years, many large independent publishers have been bought by the “Big 5” publishing houses: Penguin Random House, Hachette, HarperCollins, MacMillan and Simon & Schuster. The Big 5 now control over 80 percent of the market of trade books — general audience books that are available through most book dealers — and generate over $12 billion in revenue per year. Meanwhile, starting wages for editors at these companies have been about $40,000, which is impossible to live on in New York City where these publishers are located.

“The resurgence of union organizing is long overdue. People are finally understanding that the gap between the highest earners, the CEOs and upper management, and the lowest earners who keep the wheels turning in these industries, is obscene,” Wood said. “The gap between [News Corp founder] Rupert Murdoch and my editor is vast and deep.”

One of the demands of the striking HarperCollins workers was to raise their starting salaries from $45,000 to $50,000 a year. The company met them part way in the final contract, raising the base wage to $47,500. It’s no coincidence that MacMillan and Hachette Books, two of the non-union Big 5, just raised base wages for their workers to exactly $47,500 — a potent example of how union workers raise the bar.

"I told my 26-year old editor, ‘Jessica, you’re far too young to be an elder, but this is what elders do. They make sacrifices for the ones who are coming behind them and this is what you all have done,” she said. “‘You’ve fought this fight so that it’s going to be better for the other people coming up in the publishing industry, which has been infamously stingy with it’s largely female workforce.’”

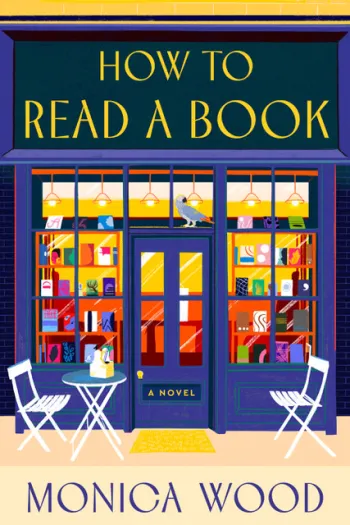

“How to Read a Book”

Wood’s upcoming novel “How to Read a Book” will be out in May, 2024. It’s the story of Violet Powell, 22, who has just been released from prison. “Shunned by her family, she finds an unlikely ally in the widower of the woman she killed.” In the meantime, Woods other books — including her bestselling memoir When We Were Kennedys: A Memoir from Mexico, Maine — are available through Powell’s Books, an online unionized book seller.

All Wood asks is that you don’t buy her books through Amazon. As one passage in her upcoming novel goes:

Baker clicked at the computer. “I can’t get the book for another week.” Leaning in again, voice lowered: “It’s two days, tops, if you go through Amazon.”

“Amazon is the devil,” Harriet informed not only Baker but whoever might be listening. She slid her credit card across the counter. “The Nazis worked with more subtlety.”