Labor History: When the Supreme Court Broke Maine’s Textile Unions

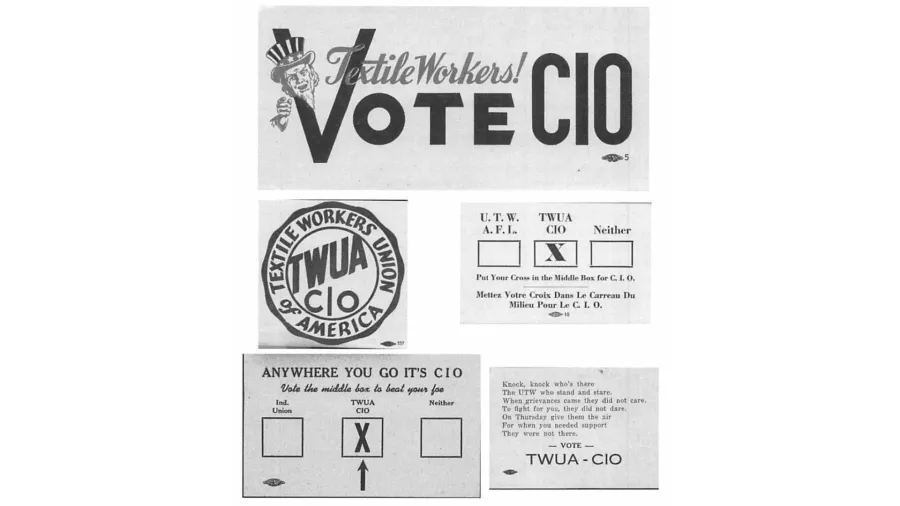

PHOTO: Organizing materials from the Maine Textile Workers Union of America, CIO.

When 10,000 Mainers joined 400,000 textile workers across the nation in a general strike known as the “Great Uprising of 1934,” there was a short window of hope before the Supreme Court stepped in and blew it all to hell.

The Lead Up to the Strike

Never before had there been such a strong showing of solidarity between northern and southern textile workers. With a 25 percent unemployment rate, it was far from an ideal economic climate for a strike, but they knew they would have to organize and fight back if they wanted a better life for themselves and their family.

Foreign competition and overproduction had caused textile prices to plummet in the 1920s and New England textile companies responded by outsourcing jobs down south to take advantage of cheaper labor and its harshly anti-union climate. Northern mills frequently used the threat that they would ship jobs south if workers stepped out of line and spoke out about unfair wages and working conditions.

Then when the Great Depression hit, mills dramatically cut their workforces, adding to the nearly 13 million unemployed workers at the height of the financial crisis in 1933. Those workers left on the job were forced to pick up the slack as management sped up production demands using a practice known as “stretch out,” forcing workers to work longer and harder for the same pay.

Despite 25 percent unemployment, the workers were pushed to the limit and many saw no other option but to strike. If it was successful, organizers hoped the strike would unite both northern and southern workers in solidarity and unionize the entire industry. Expectations were also raised with passage of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s 1933 National Industrial Recovery Act, which guaranteed workers the right to collective bargaining, though it had no mechanism to hold union elections or any legal requirement that employers had to bargain. The spark that ignited the movement was when the the National Recovery Administration granted the textile companies a 25 percent reduction of machine hours that summer of 1934.

30-year old George Jabar, a United Textile Workers of America organizer from Waterville, knew from the beginning that the workers faced an uphill struggled as they prepared for the strike. But he also held out hope that the Roosevelt administration would help find solution. Two days after the strike was called on September 3, Roosevelt appointed a Board of Inquiry led by New Hampshire Governor John Winant to investigate treatment of workers in the textile industry and come up with recommendations.

Democrats had become somewhat more pro-labor in recent years and Maine had elected Democrat Lewis Brann in 1932, one of just three elected Maine Democratic governors since the 1850s. However, any hope of sympathy from Brann was dashed the day after his re-election on September 11 when he called out the National Guard against the strikers.

As Jabar later recalled, UTWA organizers were barnstorming mill towns across the state in their “flying squadrons” in preparation for the strike when he instructed them to return their polling places and vote for Governor Brann.

“Brann was a Democrat and we, the workers, were Democrat... and he was the first one to win in 1932 when Roosevelt got it,” said Jabar in a 1969 interview. “Oh, that was ironic. Oh, I almost hit the ceiling.… September 11, he had the militia out all the over the place for no reason.”

Baton wielding police also beat back the strikers from the mill gates and forced them across the streets from mills while arresting several workers on questionable charges.

“I mean they took some of our boys [to jail] … so I went down there and I said, 'Why are you keeping them,’” recalled Jabar. “‘Well,’ they said, ‘we may send them home, we don’t want them around here.’ So we got them out, there was no bail on them, but I mean our rights [were] not like today.”

The workers certainly couldn’t count on the local media to provide balanced coverage of the walk outs. But the problem wasn’t the reporters, insisted Jabar. They were generally friendly with the workers. It was the anti-labor editors and publishers of the papers that branded Jabar as a “red” and slanted coverage to focus on chaos and disorder, rather than the demands of the workers and the behavior of the employers and law enforcement.

“Lewiston and Waterville papers.. wouldn’t give a true account. They were saying the agitators come in,” said Jabar. “The only time that they respected the labor movement was… when we started to get agreements signed and then they realized that the labor leaders and that things were not that bad.”

The Supreme Court’s Death Blow to the NIRA

The strike lasted 22 days before United Textile Workers leadership called off the strike and requested workers to return to their jobs on September 24 on the basis of the Roosevelt administration’s Textile Industry Crisis Board Report, which concluded that a whole new system needed to be established to handle labor relations. Two days later, the President issued an executive order creating the Textile Labor Relations Board to “immediately investigate, hold hearings, make findings of fact, and take appropriate action in any case in which it is alleged that there has been discrimination in taking men back to work after the textile strike.”

The board eventually held hearings in the textile towns of Sangerville and Biddeford, but it never finished its work because the following May, the US Supreme Court struck down Roosevelt’s National Industrial Recovery Act as an unconstitutional delegation of Congress’s powers to the executive branch. As a result, the President could no longer enforce labor codes contained in the act. Following the decision, Roosevelt declared war on the court. At a press conference he said, “We have been relegated to the horse-and-buggy definition of interstate commerce.”

Meanwhile, textile workers up in Maine were suffering the repercussions of their courage in fighting back against their exploitation. Companies refused to hire back many of the strikers and strike leaders were blacklisted from working in the industry. The court decision chilled union organizing in the textile industry for another two years as most workers refused to take a stand for fear of losing their jobs.

“We’d go around and try to talk people, they wouldn’t listen to you, they’d shun you,” said Jabar. "‘Get away, keep away from me,' shut the door in your face. ‘We don’t want to see you, look you cause me to lose my job.’”

The strike had generated a tremendous amount of worker enthusiasm with 3500 Maine textile workers joining theUnited Textile Workers between the fall of 1934 and winter of 1935. But the union was never able to secure contracts with any of the mills and following the Supreme Court’s ruling membership plummeted. It would take another two years following the passage of the National Relations Act in July, 1935 for the unions to rebuild the strength they had during the Great Uprising.