Labor History: When Portsmouth Naval Shipyard Workers Won Their Collective Bargaining Rights

PHOTO: Portland Press Herald, Nov. 24 1963.

On January 17, 1962, President John F. Kennedy issued Executive Order 10988, "Employee-Management Cooperation in the Federal Sector," granting collective bargaining rights to federal employees. The reform was a long time coming for the hundreds of thousands of federal workers who had been excluded from the rights their private sector counterparts enjoyed under the National Labor Relations Act of 1935.

Executive Order 10988 came as the result of findings from the Task Force on Employee-Management Relations in the Federal Service, which was created by a memorandum issued by President Kennedy to all executive department and agency heads on June 22, 1961.

In the memorandum, President Kennedy wrote that, "The participation of employees in the formation and implementation of employee policy and procedures affecting them contributes to the effective conduct of public business," and that this participation should be extended to federal employees and their unions. The Task Force had held extensive hearings, collected reams of evidence on labor relations in the federal sector and determined that granting federal workers the right to bargain collectively would actually improve the services they provide to the nation.

“The Task Force wishes most emphatically to endorse the President’s view that the public interest calls for strengthening of employee management relations within the Federal Government,” the Task Force wrote in its recommendations. “A continuous history, going back three quarters of a century, has established beyond any reasonable doubt that certain categories of Federal employees very much want to participate in the formulation of personnel policies and have established large and stable organizations for this purpose. This is not a challenge to be met so much as an opportunity to be embraced.”

The executive order gave federal workers the right to bargain over working conditions, work and vacation schedules, personnel relations, employee services, job classifications, promotion and demotion practices, reduction-in-force practices and grievance procedures. Unlike in private shipyards like Bath Iron Works, the Portsmouth workers still did not have the right to strike or to bargain over wages and other compensation. The task force had also determined that the “closed shop” model was “inappropriate” for the federal sector and that it would be optional for workers to pay dues for the costs of collective bargaining.

Despite the relatively narrow scope of the executive order, this was wonderful news for the civilian workers at Portsmouth Naval Shipyard. As we wrote in our previous story on the history of workers’ struggles at the shipyard, PNSY employees began organizing the first modern unions at the yard in the early 1900s. But they were severely limited in their ability to effect change because they weren’t legally recognized as the official bargaining agents for civilian workers. By June of 1962, the Metal Trades Council of the AFL-CIO expressed confidence that it would be able to win exclusive rights to represent all federal employees at each of the eleven Navy shipyards as well as Army arsenals and Air Force bases.

The Machinists Union had assigned 36 additional organizers to its government employee unit with more to come. On June 6, 1963, the Portsmouth Metal Trades Council officially petitioned for the exclusive recognition to represent 3,000 shipyard employees. That was also the day of their first arbitration hearing in which representatives of the American Federation of Technical Engineers and the Pattern Makers sought recognition as separate “units” in future negotiations. The Metal Trades Council was to become a third unit with Joseph C. Keraghan as president, Merle O’Donal as Vice President, and Robert Hardy as Secretary-Treasurer. In August of that year, the Defense and Navy Departments gave official recognition to the Metal Trades Council, which represented fourteen trade union locals. Its next step was to obtain authorization from 51 percent of the 8,190 workers at the shipyard.

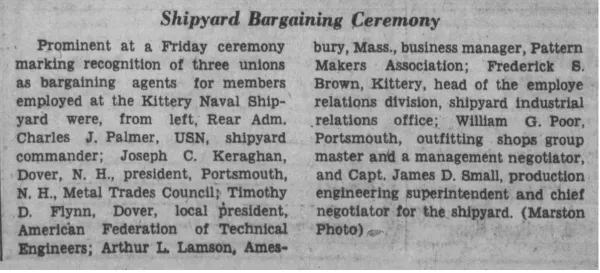

Two days after the tragic assassination of President John F. Kennedy on November 22, 1963, the Metal Trades Council, the American Federation of Technical Engineers and the Pattern Makers Association were officially recognized as bargaining agents for shipyard workers at a ceremony with naval officers. It would take another two years to finish bargaining their first contract.

Threats of Closures and Wage Disputes Roil the Yard

In the meantime, several controversies over pay and the very future of shipbuilding at the shipyard kept the Metal Trades Council in the news. Since the end of World War II, the threat of closure loomed over the yard as the Navy sought to consolidate its shipyards and shift work to private yards. At the end of the Eisenhower administration in June 1960, the Navy announced a reorganization plan to reduce costs by farming out work to private shipyards when they believed they could do the work more efficiently.

“Our problem is to reduce cost without reducing quality,” said Assistant Secretary of the Navy C. Milne at the time.

Unions and Maine and New Hampshire congressional leaders charged that the Navy’s goal was to close PNSY all together, resulting in the loss skilled workers who had pioneered nuclear submarines and benefitted private yards with their ingenuity. Workers had also been fighting for years to get the Navy to improve pay equity between PNSY employees and shipbuilders at the nearby Boston Navy Yard. From 1957 to 1961, Congress supported equalization of pay rates between the Kittery and Boston Navy Yards, but could not garner support from President Dwight D. Eisenhower.

In July 1960, the Navy announced a miserly 1 cent per hour average increase for Portsmouth workers, far short of the average 2.5 cent hourly increase given to Boston Navy Yard employees. By law, the Navy’s wage scales were pegged to wages paid by private industry in the immediate vicinity of naval installations. President Eisenhower twice vetoed a bill that would have equalized pay at the Portsmouth and Boston yards, arguing that it would “unsettle the economy of the Portsmouth area.” This infuriated Portsmouth workers who were getting less for doing the same work as their Boston workers.

Joseph C. Keraghan, President of Portsmouth Metal Trades Council retorted that Eisenhower believed “what is good for big business is good for everybody, regardless of what injustice it may entail.”

“We can only feel that the Navy is guilty of less than fair-mindedness when it is realized that it has held up the implementation of a wage survey for eight months,” he told the Concord Monitor on July 15, 1960.

Unions enthusiastically supported the nomination of John F. Kennedy when he was nominated for President on the same day, even if some leaders were less than enthused with his pick of Senate President Lyndon Johnson for his running mate. In March of 1963, the Portsmouth Metal Trades Council met with the Maine and New Hampshire Congressional delegations to call for a six-part program to support the shipyard. It included the elimination of the 35 percent allotment to private yards, a more equitable formula for the awarding of contracts and awarding more new construction to public naval yards; a due checkoff system; and equalization of wages between Boston and Portsmouth.

Kennedy’s election didn’t stop the Navy’s plan to consolidate Navy yards. In the summer of 1963, Rear Admiral Charles A. Curtze, caused an uproar at the yard when he blasted Portsmouth workers in response to a question from Democratic Maine Senator Edmund Muskie about why the shipyard was doing so poorly.

“They don’t work,” Curtze said without hesitation. “It is as simple as that.” He added that he worked at the yard from 1938 to 1940, but it had changed. “What I remember from 30 years ago - it is not the same shipyard.”

Rear Admiral Willam A. Brocket, the chief of Navy Bureau of Ships, backed up his deputy and repeated a warning to the yard that it would have to “shape up” if it wanted to obtain new work in 1964. He said he planned to cut the PNSY workforce from 9,000 to 6,000 if no new sub work was awarded to the yard in 1964. Brockett said that Navy shipyards were not in danger of closing but would probably do more overhauling and repair work than shipbuilding. “Frankly it will plummet,” he said.

Union leaders were furious at the Navy’s characterization of their members. Metal Trades President Keraghan called the Navy’s comments a “public indictment of proud and capable workmen and a gross insult to labor” in a telegram to AFL-CIO President George Meany.

Vice President O’Donal retorted that work at the yard “has always been superb” and claimed the derogatory comments were “just a disguise” for an attempt to take new construction away from Kittery. He said many subs built in civilian yards were sent to Kittery to be brought up to naval specifications. He noted that his members had been correcting the mistakes of other private yards for several years now.

“The Abraham Lincoln, a subpolaris sub, was built here and it’s the only one of its type that didn’t need its regular overhaul this year because it was so well built,” O’Donal said. “The Bureau of Ships has wanted to close the yard and keep submarine building in the laps of private yards.”

Senator Smith Margaret Chase Smith later released a report that found PNSY actually had the second lowest costs per hour of any of the eleven government yards.

two.jpg)

The submarine theUSS Abraham Lincoln

In December of that year, the Department of the Navy approved a four cents average hourly wage increase for the Portsmouth workers, but it was still well short of what Boston workers were paid.

“Although I am pleased that the workers at the Kittery Naval Shipyard have received a wage increase, I am disturbed that the increase of seven cents an hour recently announced for workers at the Boston Naval Shipyard adds three cents per hour to the wage discrepancy between the two yards,” said Senator Muskie. “I plan to continue to press the administration for wage equalization. Equal pay for equal work is a right to which Kittery-Portsmouth workers are entitled.”

Keraghan, the council president, called the wage adjustment “disappointing,” noting that the union carried the fight for equal pay for equal work twice to the President and for 15 years had fought to get blue collar shipyard workers fair wage rates. Ermanno Rossi, president of the Pattern Makers Association, said that the wage schedule was “completely unrealistic and unfair.” He said that it places the pattern makers at a 45 cent-an-hour disadvantage with the rate paid in Boston. He said “we find out wages determined by bureaucratic fiat which works against us.”

The same month, more news headlines spelled doom for both the Boston and Portsmouth shipyards. Senator Smith told reporters that PNSY was “on the way to being closed.” The following month, she told the Portland Press Herald if the economic burden of the Navy yards outweighed the benefits, then the yards should be closed, telling workers to “work hard and hope for the best.”

Later that spring, U.S. Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara said that while PNSY would have to cut costs, “we don’t believe that the high costs are a reflection of the attitude of the employees or a lack of skill of the employees… It’s a management responsibility. We accept it here. We propose to act to reduce those costs.”

Metal Trades Council Wins Its First Contract

Finally, on October 16, 1964, the first collective bargaining agreement between the Metal Trades Council and Kittery-Portsmouth Naval Shipyard was signed. The agreement, which covered over 5,000 ungraded, nonsupervisory employees at the shipyard, covered working hours, leave, safety, training and grievances. Recently-elected Metal Trades Council President Merl O’Donal, a Smithfield, Maine native, said the agreement was the product of much hard work, research and thought, “and through it we hope to be able to better represent all those employees within our unit.”

“I cannot emphasize too strongly the necessity for both management and labor to live up to not only the letter of the agreement… but also the spirt of each,” said O'Donal. “I know it is impossible for labor and management to always agree; however, in the spirit of the executive order, each, through mutual respect, should make an earnest attempt to understand the other’s position and reasons for it.”

Captain William C. Hushing, the shipyard commander, said the agreement was an important event “in an industry such as ours” and “a clear indication of our support of the program.”

Hushing expressed hope that the agreement would boost the morale of employees, improve efficiency at the yard, and build a better image of the shipyard by reducing costs.

Both Republican and Democratic administrations continued to support collective bargaining rights for federal employees for the next six decades. A special review committee appointed by President Johnson found in 1967 that Executive Order 10988 had produced “excellent results” that were “beneficial to both agencies and employees.” Additionally, the committee found that the new policy “contributed to more democratic management of the workforce and marked improvement in communications between agencies and their employees.” It also resulted in "improved personnel policies and working conditions,” the report found.

In 1969, Republican President Richard Nixon expanded collective bargaining rights for federal workers, creating guidelines for unfair labor practices and authorizing the use of binding arbitration in certain disputes. Executive Order 11491 also established the Federal Labor Relations Council to oversee the program, hear appeals and decide cases. Like Kennedy, Nixon argued that collective bargaining not only benefitted workers, but improved the mission of their departments.

In 1965, Secretary McNamara ordered the closure of 95 military bases, including Portsmouth Naval Shipyard. However, it was given a ten-year extension before the order to close was rescinded by President Richard Nixon in 1971. The Boston Navy Yard, on the other hand, was decommissioned in 1974. The last new submarine constructed at Portsmouth Naval Shipyard yard was the Sand Lance in 1971. It currently only overhauls, refuels and repairs vessels. In 2005, the shipyard was once again placed on the list for base closures and scheduled to be shut down in 2008, but it was removed from the list once again. In recent years, the shipyard has expanded with the construction of additional dry-dock capacity.

2025 and Beyond

In 2025, Portsmouth Naval Shipyard workers are once again faced with extreme challenges after President Donald Trump stripped them of their hard-won collective bargaining rights. But the workers have persevered through many other struggles before. From guarding the port against the threat of the British Navy during the War of 1812, to launching wild cat strikes throughout the 19th century and forming unions in the early 1900s, they have fought for their rights and economic interests long before the government legally recognized their right to exist. They will continue to stand strong, organize and fight back against forces that seek to destroy everything they fought for over the past 225 years.