Labor History: The Two "Mavericks" of Maine's Labor Movement

PHOTO: 1942 Maine State Federation of Labor Convention, front row — Charles O, Dunton of Rumford, J.W. Townsend of Woodland, Benjamin Dorsky of Bangor, president. Back row” R.W. Gustn of Bangor, J.F. Wheeler of Millinocket and Horace E. Howe of Portland.

On June 19, 1934, the largest delegation of union members in the Maine State Federation of Labor’s history gathered at the American Legion Hall in Augusta for the state AFL federation’s 30th annual convention. More than a dozen of the unions represented had just recently affiliated in the past year, according to organizers. “Many new faces,” both men and women, had never before attended a state branch convention and were “primed with new ideas rarin’ for action.”

Unlike previous conventions, there were several delegates from newly formed unions in the textile industry. The labor movement was energized by President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s National Industrial Recovery Act, which included provisions to require employers to collectively bargain with their unionized employees for the first time.

Among the younger delegates were 30-year old George Jabar of Waterville, an organizer with the United Textile Workers of America (UTWA), and 31-year old Benjamin Dorsky, a delegate from the Bangor Motion Picture Operators Union Local 198. Both men came from immigrant backgrounds. Jabar hailed from a Lebanese family in Waterville, while Dorsky was a Russian Jewish American immigrant.

However, as the Kennebec Journal noted, there were also a “goodly number” of longtime delegates who are “inclined to lean toward conservative methods.” At the time, the federation was largely made up of white men, the descendants of the earliest English settlers and Irish immigrants who arrived on Maine’s shores in the mid-19th century. Many of them were members of the building trades unions, which were the most powerful unions in Maine at the time.

Jabar estimated that the textile industry was made up of 80 to 90 percent French-Canadian workers, many of whom came to Maine's mill towns from small farms in Quebec.

“They were uneducated. I don’t think you had one who had probably a higher than fourth, fifth grade or sixth grade education,” recalled Jabar. “In Biddeford a lot of people couldn’t speak English. Lewiston was the same way. The only [places] where they were Americanized was in the small areas like in Dexter and Pittsfield. They were French-Canadian, but they were Americanized.”

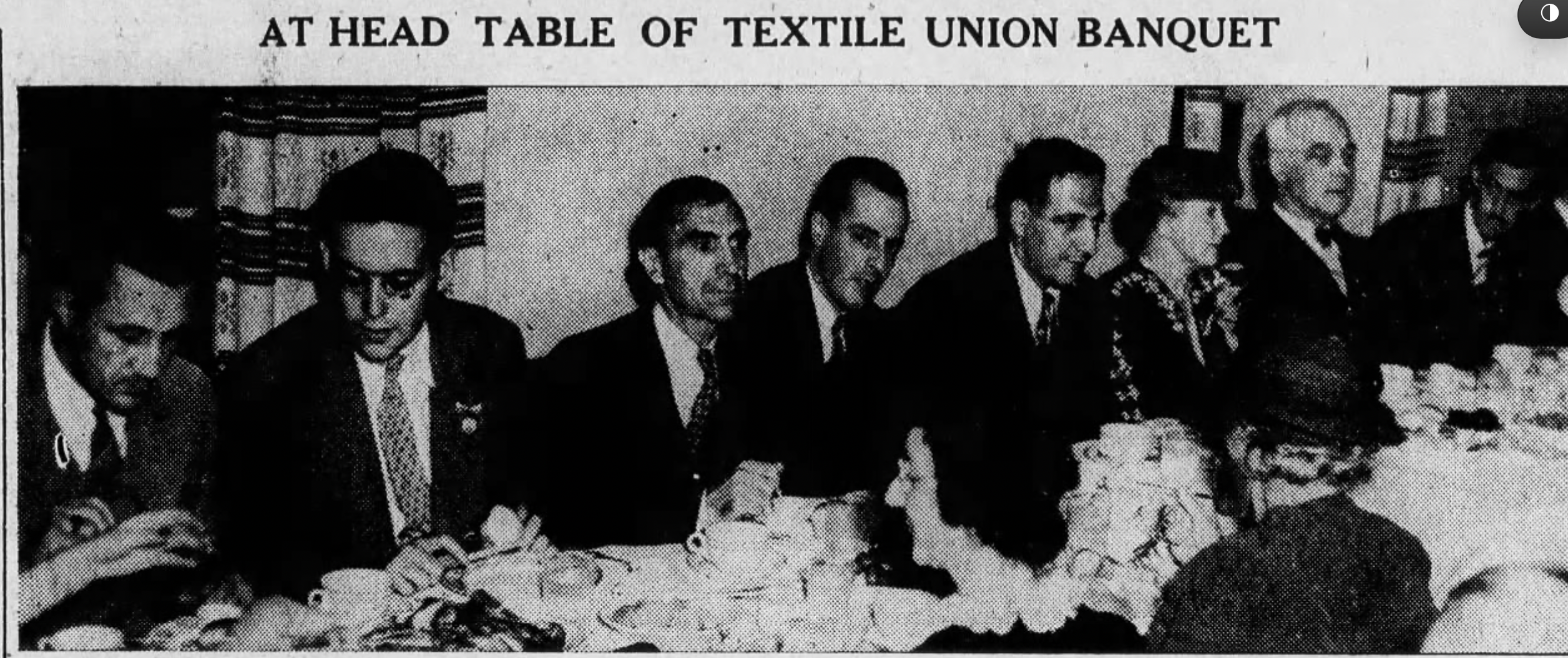

PHOTO: 1943 Textile Workers Union of America banquet. Fifth from left - TWUA State Director George Jabar.

As a Catholic, Jabar had attended parochial schools so he could understand some French, but he knew he really needed a French speaking organizer to reach all of the workers. There was also a widespread belief that French Canadians were adverse to unions.

“They don’t fight city hall,” said Jabar in a 1972 interview. But, he quickly added, “once you get them together, I mean they’re hard to beat.”

It was much easier, Jabar believed, to organize workers from places like Italy, the UK, Germany and Poland where workers had more knowledge of unions and many of them had been members of socialist parties. Management typically sought to use ethnic differences as a wedge to divide workers whenever they could. In those days, there was an ethnic hierarchy in the textile industry. The English held the management positions while skilled trades like dyeing were held by Germans and bleaching was dominated by the Irish. The French, on the other hand, had trouble getting into those higher paying trades. Like all non-union industries, favoritism was rampant.

Since its founding, the Maine State Federation of Labor was staunchly opposed to immigration from anywhere but Northern Europe. In 1923, the MSFL Convention passed a resolution opposing all immigration from countries in Southern Europe like Italy and Greece. The resolutions stated that the federation was not in sympathy with those who wish to admit “hordes of uneducated and unskilled laborers to be exploited by the great employers of labor and brought thus to form the lever to increase hours of labor.”

"While the federation does not favor the bringing to our shores of the hordes from 'southern Europe,' the convention declared, "it does gladly extend the hand of welcome to the stalwart and intelligent immigrants from the north of Europe because of their easy assimilation of American ideals and their staunch support of the principles of our government.”

Little did they know that the two largest labor organizations in the state would one day be led by a Russian Jew and a Lebanese textile worker.

The 1934 Convention passed resolutions opposing a proposed state sales tax and supporting the establishment of a special fund to pay workers compensation claims and the creation of an unemployment insurance program. The delegates also voted to raise per capita dues to have the Maine State Labor News delivered to all AFL members. In addition, the convention established the federation’s first full-time paid position to handle organizing and legislative affairs.

However, younger delegates like Dorksy and Jabar were fed up with business as usual at the State Fed and were determined to make their voices heard. The two young “mavericks,” as Jabar described Dorksy and himself, felt that “the old timers” clung to power over the federation using un-democratic means. When it came time to elect officers, he said one man would get up and nominate a slate from the President on down and then the Vice President would nominate the slate of executive board members, which was immediately followed by another motion to nominate the VP.

“I get up and I hit the ceiling. I was, you know, “What goes on, what kind of organization…?’” And then Dorksy followed me out,” Jabar recalled chuckling. “Well, the irony [is] that he became the president of [the Maine State Federation of Labor] later and I became president of the CIO and for twelve years… we were on either side of it… trying to get kids to join our group.”

Later that year, thousands of Maine textile workers joined the Great Uprising of 1934 in a general strike, which ended in defeat in the short term after the Supreme Court effectively repealed their collective bargaining rights. Jabar worked within the state federation to pass a resolution calling for a law clarifying the right of workers to picket peacefully in response to the mass arrests of striking workers outside factory gates that September.

As Jabar explained, there was no law governing where workers could picket before 1948 so the police just made up arbitrary restrictions. In 1948, he pleaded his case to notorious anti-labor Supreme Court Judge Harry Manser, who was most known for breaking the 1937 Lewiston-Auburn strike and sentencing union leaders to jail time. Even Manser had to admit that there wasn’t a limit on how far workers could picket as long as they let people in and out of the business.

But while United Textile Workers (UTW) leaders in Maine continued to work collaboratively with their state federation, riffs were opening up between the more progressive union and the national AFL. At UTW's convention in 1934, national UTW leaders called for more emphasis on forming industrial unions as opposed to the AFL's traditional craft union model. At the 1935 National AFL Convention a year later, UTW introduced a resolution to study the potential of forming a third party while condemning both major political parties for failing to protect strikers and address rampant income inequality. The resolution failed, but the union was heading for a split with the more conservative federation and into the arms of the Congress of Industrial Organizations. UTW President, Thomas McMahon, would later become one of the charter members of the CIO.

Next week: Passage of the NLRB Unleashes Massive CIO Organizing Wave in Maine.