Labor History: The Punch that Launched the CIO

PHOTO: John L. Lewis & Bill Hutcheson.

On the final day the of the 55th Annual Convention of the American Federation of Labor in Atlantic City on October 19, 1935, years of tensions between craft unionists and industrial unionists exploded with a punch in the face that sent shockwaves through the labor movement.

For years, the pugnacious United Mine Workers of America President John L. Lewis and other more progressive labor activists had been unsuccessfully bird dogging the AFL’s entrenched leadership to more aggressively organize the nation’s industrial workers. As workers across industries became increasingly militant, the industrial unionists feared the labor federation was failing to seize the moment.

Beginning in the 1890s, the AFL union focused organizing on the most skilled workers, the “labor aristocracy,” and wrote off the masses of unorganized industrial workers who were largely women, immigrants and people of color. This practice earned the AFL the nickname the “American Separation of Labor” among its pro-industrial union critics. Since the craft unions weren’t organizing the so-called “unskilled” workers, radical left-wing unions led by the syndicalist Industrial Workers of the World, Socialists and the Communist Party stepped in to organize them. At times, the AFL even went out of its way to try to help management break IWW strikes and organizing drives.

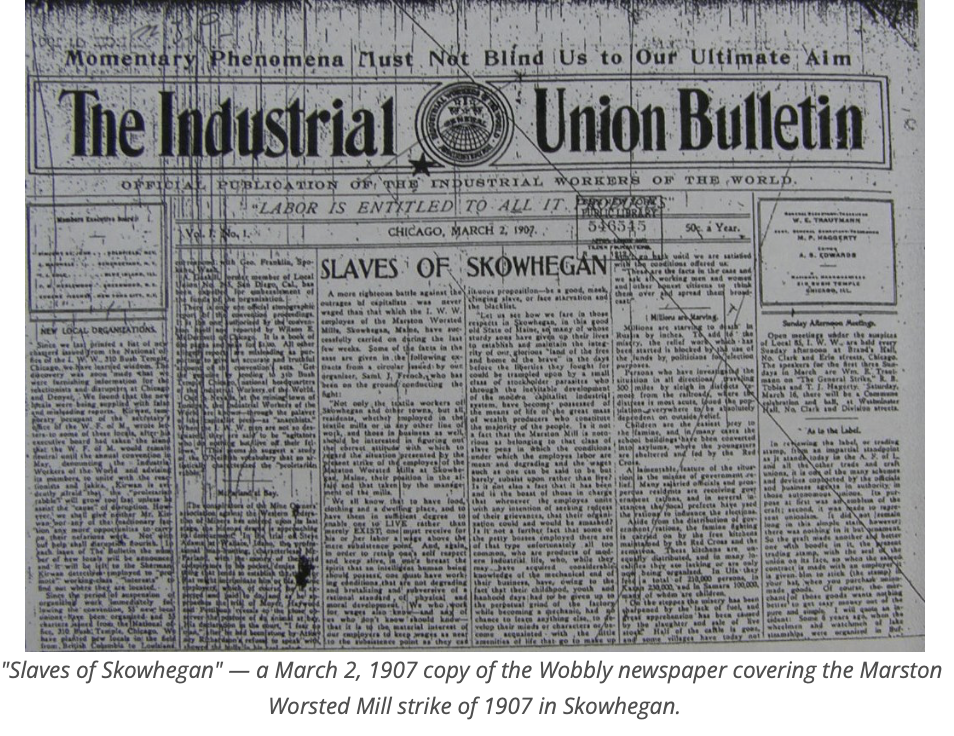

Notably, when 225 mostly women workers with the IWW went on strike at the Marston Worsted Mill in Skowhegan in 1907, John Golden, President of the craft-oriented United Textile Workers of America, an AFL union, offered to send in strikebreakers. For his efforts to defeat the IWW during the "Bread and Roses Strike" of 1912, the Wobbly troubadour Joe Hill immortalized Golden in the song "John Golden and the Lawrence Strike." By the 1930s, much of the AFL's old guard had come up through the union ranks in the early 1900s.

Leading the arch conservative block was 61-year old Carpenters Union President Bill Hutcheson, who not only opposed organizing mass production workers in steel and auto manufacturing, but worked actively to defeat those efforts. Once he even convinced the Teamsters to refuse to haul wood from a dissident CIO faction of lumber workers who had split from the Carpenters. While Hutcheson was known for his ruthless and unethical tactics, especially in jurisdictional fights with other unions, he had also built the union into of the most powerful affiliates in the AFL since his first election in 1915.

55-year old Lewis — who had spent many years working in the steel, rubber, glass, lumber and copper industries prior to becoming UMWA President — had grown frustrated with AFL’s strategy to separate workers by craft after witnessing first hand how it failed the vast majority of workers.

“Then, as now, the American Federation of Labor offered to the workers in these industries a plan of organization into Federal labor unions or local trade unions with the understanding that when organized they would be segregated into the various organizations of their respective crafts,” said Lewis on the floor of the convention. “Then, as now, practically every attempt to organize those workers broke upon the same rock that it breaks upon today – the rock of utter futility, the lack of reasonableness in a policy that failed to take into consideration the dreams and requirements of the workers themselves, and failing to take into consideration the recognized power of the adversaries of labor to destroy these feeble organizations in the great modern industries set up in the form of Federal labor unions or craft organizations functioning in a limited sphere.”

During a floor debate on a request of the rubber workers union for an industrial union charter, all hell broke loose. Speaking for the rubber workers, delegate William Thompson, argued that a proposed charter granting his union jurisdiction over 90 percent of the production workers and reserving to 10 percent of the remaining workers for craft unions was unworkable. He said that several times he and his coworkers had organized rubber workers into an industrial union, but that the craft unions had selected their own men from the group to the detriment of the industrial union.

Upon warning the convention that the rubber union would never again accept such an arrangement, Hutcheson shot to his feet to raise a point of order. He argued that the industrial union question had already been disposed of when the convention defeated the policy earlier. Lewis countered that Hutcheson's point of order was “small potatoes” and was meant to silence smaller unions. The burly Hutcheson, standing at 6 foot 3, replied that he had been raised “on small potatoes and that is why I am so small.” After AFL President William Green ruled in Hutcheson favor, Lewis marched across the floor and, following a brief animated conversation, clocked Hutcheson with a right to the jaw, sending him crashing to the floor amid the wreckage of a table.

According to the NY Times, shortly after that, Lewis received a telegram from a union carpenter from Kansas City: “Congratulations, sock him again.”

In the annals of the labor movement, the blow signaled to millions of workers across the country that John L. Lewis was a fighter for the unorganized worker.

Shortly after, Lewis co-found the Committee for Industrial Organization within the AFL, which changed its name to the Congress of Industrial Organizations when it broke away from the AF of L in 1938. Its founding unions included leaders of the United Mine Workers, International Typographical Union, the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America, International Ladies Garment Workers, United Textile Workers, the Oil Workers Union and the Hatters, Cap and Millinery Workers and the Mine, Mill and Smelters Union. At the 1938 CIO convention, Lewis was elected as the upstart labor federation’s first president.

Next week: the founding of the Maine CIO!