Labor History: Organizing the South Portland Shipyards

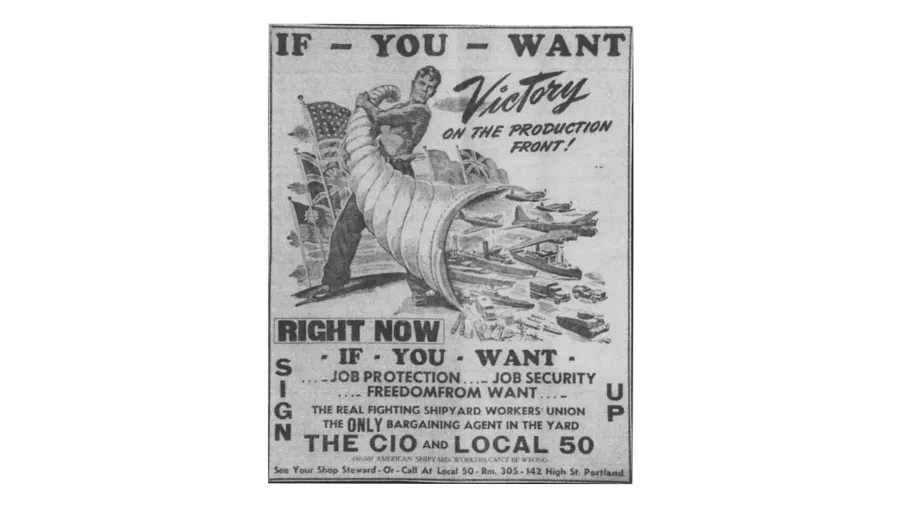

PHOTO: IUMSWA Local 50 ad in the CIO newspaper the Yard Bird, which was circulated in the South Portland shipyards in the early 1940s.

In the fall of 1941, Bath Iron Works welder and CIO union organizer Arthur Lebel headed forty-four miles down the coast to South Portland to set up a new office for his next organizing drive. Months earlier he and his CIO brothers and sisters suffered a heartbreaking defeat to the new Independent Brotherhood of Shipbuilders, a more company-friendly union that eschewed strikes and shied away from confrontation with the company.

“I was the first one there [at the South Portland yards], and I think I was the key organizer there,” recalled Lebell in a 1972 interview.

Lebel was determined that this time would be different. He and his colleagues brought in a typewriter and a mimeograph machine and ran off thousands of leaflets to distribute at the gates of the South Portland yards.

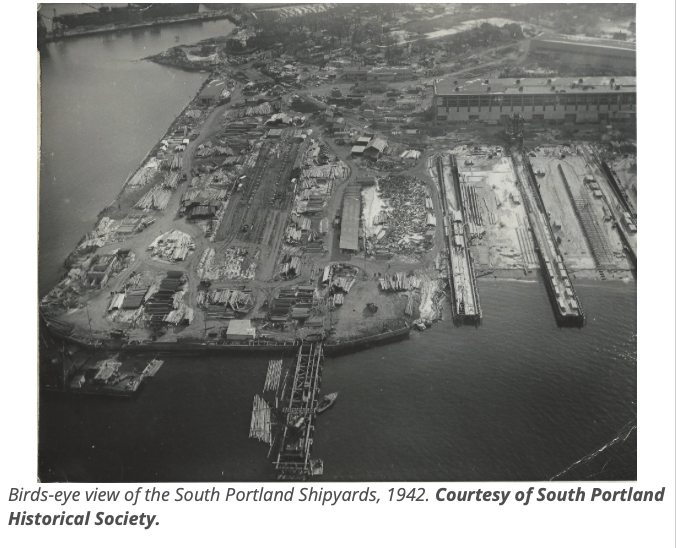

The previous year, union construction workers began work on the Todd-Bath Iron Shipbuilding Company (TBISC), known as the East Yard, for the construction of freighters for England on the South Portland waterfront. The adjacent South Portland Shipbuilding Company (SPSC), known as the West Yard, also began construction on a new yard to build cargo ships.

By the time Lebel arrived, there were about over 6,000 workers at the two South Portland yards and 6,000 at Bath Iron Works. The three companies had hired a whopping 10,200 shipbuilders in just two years. Shipbuilders complained that they were earning less than other workers in the defense industry. The cost of living was surging and affordable, quality housing was very hard to find.

Horace Howe, president of the Portland Central Labor Union, and Vice President of the Maine Federation of Labor, noted that there was no standard for the crafts at the yard and some machinists were making as low as 66 cents an hour, $13.79 in today’s dollars. Workers also complained of the lack of parking spaces to accommodate the thousands of commuters. While Todd- Bath management had their own reserved parking spaces, the shipbuilders received "continual tickets.” It was the perfect union organizing opportunity and the elections were hotly contested.

The Portland Central Labor Union was not about to let such a massive workforce become enticed by the promises of the International Union of Marine and Shipbuilding Workers (IUMSWA), CIO. But the two rivals found common cause in their passionate loathing for the Independent Brotherhood, which claimed it had 3,500 members at Todd-Bath. The AFL and CIO called it a “company union” to anyone who would listen.

The AFL argued that "the fact that the president of the independent union does his organizing work on the company’s time, indicates that the shipyard organizations are company and not independent unions.” The powers that be certainly favored the Independent Brotherhood. After the Independent Brotherhood held a meeting at the South Portland City Council Chambers, the CIO was denied use of the venue on the grounds the chambers were for local organizations only,” wrote Charlie Scontras in his book “Labor in Maine: Building the Arsenal of Democracy.” The denial was yet another example of how CIO supporters were treated as “outside agitators” rather than the local workers that they were.

During the BIW union drives, Todd-Bath President William S. Newell, who was also president of BIW, made no secret of his support for the the weak Independent Brotherhood and even helped fund its successful union drive at BIW. In those days, defense industry contractors knew that their workers would eventually unionize, so they tried to sway them to choose less militant options.

As Scontras wrote, members IUMSWA Local 50 distributed leaflets and held meetings in both English and French, not only in the South Portland area but also in Saco, Biddeford, Sanford and other towns where shipbuilders lived. At the meetings, the workers played union records and sang rousing labor songs. CIO members called for the creation of housing committees for Portland and South Portland and demanded that workers have representation on these boards.

They also accused the company of hiring learners who deprived first class mechanics of work. “Favorite sons,” they argued, were given all the overtime works at the expense of seniority. CIO leaders said the company classified everyone in the outside hull department — with the exception of the chippers, drillers, riveters, and a few other outstanding crafts — as shifters' helpers. As a result, whole job classifications were eliminated resulting in wage cuts.

The CIO also took aim at the Independent Brotherhood’s contract with BIW that ensured Bath workers would not lose their seniority if transferred to the South Portland yard. This meant South Portland workers could be replaced by Independent Brotherhood members when work was slack, undermining job security in favor of "the inner circle of the Bath company union.” The CIO ridiculed the fifty cents a month dues required by the Independent for “misrepresentation.” Meanwhile, the company was raking in massive profits from government contracts.

Lebel recalled workers coming into meetings to learn more about the benefits of unionizing with the CIO. Soon they were forming organizing committees in each department and workers began wearing buttons and signing authorization cards.

“We talk about the conditions under which the people are working,” said Lebel. “We compare the wages with unionized shipyards and let the workers think about it and make a decision. And it's just like any election process, you put your best foot forward and, you don't make any promises to the workers, but you point out what they can do if they band together.”

The union election for Todd-Bath workers was to be held on March 12, 1942, IUMSWA, CIO, AFL Metal Trades unions and the Independent Brotherhood were all on the ballot.

A week before the election the 60,000-member Maine AFL’s news organ Maine State Labor Newsran a headline expressing confidence that South Portland workers “will not vote for the Communist-Dominated” CIO alongside a photo of a violent strike with the caption “Authentic Picture Taken During a CIO Strike.” The sub-head blared:

“Maine Workers Regarded as Too Intelligent to Become Tied Up With An Organization That Sponsors Sit-Down Strikes and Other un-American Methods During Controversies — Recall How CIO Reversed Anti-Defense Policy When Nazis Invaded Russia, and Also Its Fight to Free Browder and Persistency in Keeping Communists and Fellow-Travelers in Office"

However, the AFL’s red-baiting failed. When all the ballots were counted, 3,620 workers voted for the CIO, 1,529 for the AFL, 513 for the Independent Brotherhood, and 353 for no union out the 8,614 eligible voters. After years of false starts, the CIO supporters had overwhelmingly won their first union election at a Maine shipyard.

This time the company surprisingly remained neutral in the election, which Lebel attributed to high profits. The Shipyard Worker reported that Todd-Bath was resigned to the fact that the CIO would win the election and “therefore there has been no intimidation or coercion whatsoever on the part of the foremen and other company men to force our men to remove their buttons.” Scontras noted that CIO buttons were seen everywhere from the streets and buses to restaurants, and clubs. The victory was so overwhelming, according to some workers, that the ground was covered with AFL Buttons "which had been thrown away by men ashamed to be seen wearing them,” wrote Scontras.

On May 4,1942, IUMSWA Local 50 and Todd-Bath signed a new contract that included a raise from 66 cents to between 72 and 78 cents an hour, a dues checkoff system, grievance procedure; seniority provisions, one-week vacation for those employed for one year, and two weeks vacation for those who were employed for two years or more; time and a half on Saturdays and double time on Sundays, and on nine specific holidays.

The contract included a no-strike or lockout provision for the term of the agreement and created a closed shop where dues were compulsory as a condition of employment. The workers agreed to waive vacation time and instead took their vacation pay in the form of war bonds and stamps. Employees who were drafted into the war were given bonuses. The contract was followed by the reclassification of all employees of the Todd-Bath shipyard which meant pay increases, depending on the skill and ability of the individual employee.

Some workers who voted against IUMSWA were not happy to learn that they would be obliged to join the union or leave the yard. As Scontras notes, some questioned how the CIO could declare a “closed shop” during war time when all hands were needed on deck. IUMSWA countered that they could keep their AFL cards as long as they paid CIO dues.

"It's about time we found out who is running the country—the Government or the CIO. We've all heard the slogan 'No walkouts. No lockouts, No strikes in war time,' but this looks every much like a lockout when they can tell us where to work,” one disgruntled shipyard worker bitterly told a reporter. He added, "I don't know who's to blame,” but it looks to me as though it were Pres. Newell."

As Scontras noted, the comment blaming Newell for the CIO victory could be traced to the fact the BIW President actually encouraged his workers to join unions and was outspoken in his acceptance of the closed shop. In all likelihood he changed his position to create a more stable, predictable and harmonious workplace free of labor strife so he could meet tight contract deadlines.

After all, the Independent Brotherhood’ proved it could not control the wildcat strikes that rocked the open shop BIW shipyard that year. At the time, Newell's acceptance of the closed ship was an unprecedented decision by a corporate executive in Maine because the open shop was seen as the “hallowed principle in labor-management relations,” wrote Scontras. At the same time, Newell also provided the same contract gains that the IUMSWA won in South Portland to BIW workers — a move that the CIO viewed as an effort to prevent it from organizing the Bath shipyard.

AFL organizer and leader Alonzo Young believed the odds “were too great” for the craft unions to beat the industrial IUMSWA. The Maine State Labor News argued that CIO had a longer presence at the yard and it was able to out-organize the AFL union. The CIO reportedly had 300 full and part-time” CIO workers stationed inside and outside the yard to engage workers.

Others "rang door bells all hours of the day and night during the entire organizing campaign” while the CIO targeted welders, burners and tackers with large ads in daily newspapers stating the AFL had refused to charter them into an international union. Unlike the CIO, the labor paper complained, the AFL had run a "clean-cut campaign” which contained no "abusive" statements about the CIO.

Although the AFL had suffered a series of defeats at Maine shipyards, it wasn’t out of the game. In January we will cover the AFL’s spectacular comeback at the nearby SPSC yard.