Labor History: Maine Workers Mobilize for Wartime Production

In our latest segment on the role of Maine workers in the war effort during World War II, we borrow liberally from the late labor historian Charlie Scontras’ book “Labor in Maine: Building the Arsenal of Democracy and Resisting Reaction at Home, 1939-1952.”

A year and half before the US officially entered World War II, Maine Governor Lewis Barrows was already taking steps to prevent espionage and sabotage of critical installations in the state. The Governor ordered guards on 24-hour watch over Maine’s 32 armories, arsenals and military stores. Soldiers in Maine’s National Guard immediately began training for “mock wars” and fifteen privately organized defense units with approximately 1,100 men were drilling weekly by the fall of 1941.

Barrows also issued a proclamation requiring foreign nationals to register with the state and by July of 1940, 20,000 New Mainers had complied with the order. The state went so far as to confiscate the cameras, guns and short wave radios of Italian immigrants and didn’t return their possessions until 1944.

After the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, Maine went into full-wartime production mode. Shortly after the attack, John R. Newell, Assistant Manager of the Bath Iron Works Corporation, expressed fear that the shipbuilding city of Bath could be a target for enemy bombings like the German air raids of Coventry, England a year earlier.

“If Bath is bombed—and it may come tonight or tomorrow night—there will not be just two or three bombs or two or three fires, for I believe it will be an effort to make Bath another Coventry,” he told the Lewiston Daily Sun.

The Maine National Guard was ordered to “remain on alert, the State Police were put on standby for emergency calls and Deputy Sheriffs were required to be subject to 24-hour duty if needed. The same month, the Civilian Defense Commission announced that a network was set up to monitor forest-stream areas for saboteurs targeting the hydro electric dams that powered Maine’s war industries. In February, 1942, an active mine field was placed at the entrance of Portsmouth Harbor to protect Kittery Naval Shipyard from German submarines. The Coast Artillery positioned its mobile artillery to protect the Portland Harbor.

In a simulation of dive-bombing attacks, fifteen Navy planes “bombed” Portland Harbor, while the city’s Portland Public Works Department distributed sand to residents for extinguishing incendiary bombs. Air raid drills were frequently practiced in Portland and in other towns by ringing church bells and turning off street lights until air raid sirens were secured.

Citizen groups were also organized to monitor various parts of the state. The American Legion had more than 500 air warning observation posts with more than 10,000 watchers who were under the direct supervision of the Army. The states Forestry Department enlisted its wardens and 20,000 Sportsmen's Club members to ensure the protection of the state’s natural resources like timber. The State's Fish-Game Commissioner, George J. Stoble, promised a "warm reception" to anyone who planned to sabotage the forest lands of the state.

10,000 local fishermen were recruited to be the “eyes and ears” of the coastline by watching for any suspicious crafts. Boaters in. Portland formed a a Coast Guard auxiliary flotilla to patrol Casco Bay. Mainers were told to be on the look out for “fifth columnists” who secretly aided the enemy. The State Police investigated immigrants building warships at Bath Iron Works and required all of the workers be finger printed.

Maine’s Health Department made efforts to get all Mainers vaccinated for diphtheria, typhoid fever, and smallpox in case the state’s water supplies were damaged in an enemy attack. Local fire departments were trained to handle potential fire bombings.

Maine Workers Mobilize for Wartime Economy

Even before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941, Maine’s wartime economy was booming as Mainers worked around the clock to fulfill orders for Navy warships, ammunition, gun mounts, airplane parts, propellers, gas mask bags, bullet-making machines, submarine components, toothpicks, smokeless powder, paperboard containers for shells, paper parachutes, blood plasma kits, food and much more.

"Virtually every industry in Maine today is working wholly or partially on so-called war orders or is engaged in making goods necessary to the national comfort or morale,” remarked State Safety Director Arthur F. Minchin on Sept. 8, 1941.

Unionized workers in the state's textile hubs were busy making fatigues, parachutes, blankets tents and all types of clothing and accessories for the soldiers on the front lines in Europe. Shoe factories produced shoes for nurses and refugees, Alaskan snowshoes, laced leather boots and harnesses while cannery workers produced Turshonka, a canned stewed pork for Soviet troops.

In 1943, the New England Shipbuilding Corporation, which included the Todd-Bath Iron Shipbuilding Corporation and the South Portland Shipbuilding Corporation in South Portland, Bath Iron Works in Bath and the US Navy Yard in Kittery employed nearly 60,000 workers, including 8,526 women to help build the Navy’s war fleet. By 1945, Maine shipbuilders had built 234 Liberty Ships, sixty-four destroyers and seventy-one submarines. Even smaller shipyards in Maine in Mount Desert Island, Camden-Rockland and Boothbay were kept busy building minesweepers, salvage vessels, submarine net tenders, picket boats, barges, transports, and other vessels.

The wartime boom pulled thousands of Mainers out of the Depression as unemployment plunged from 17.2 percent in 1939 to less than 2 percent in 1945. The state Health and Welfare Commissioner reported that "scarcely an employable person remains on Maine's dwindling emergency aid rolls and virtually all employables have been weeded off direct relief.”

The wartime boom of high-paying defense jobs in the shipyards created massive labor shortages in lower paying industries like farming, canning, textiles and shoe factories. As a result, schools in Aroostook County had to delay the start of the school year to allow students to harvest all of the food. The number of minors issued work permits nearly tripled from 1940 to 1942 with 6,520 youths employed. Even teachers were asked to join the harvest alongside their students during their summer breaks.

Because so many textile workers left the mills of Lewiston to work in the South Portland yards, it was said that "Lewiston mills help built the shipyards.” Hundreds of Jamaican laborers recruited by the War Food Administration to harvest canning crops and potatoes in Maine were also hired to fill positions at Southern Maine foundries.

People with disabilities were also encouraged to join the workforce to support the war effort. One report described how fifty invalid women in the Penobscot region were working from home, making mesh bags from twine for the Navy.

"Cripples [were) no longer barred from war worker ranks. The lame, the halt and the blind, today loomed as a saving grace as employment agencies throughout this area sought frantically to fill unprecedented demands for able bodied workers in the accelerated war effort,” reported the Portland Evening Express in April, 1942. “Men and women, normally barred from competition for jobs because of amputated arms, hands or legs, failing sight, shriveled limbs, faltering hearts, and numerous other physical defects are beginning to be recognized as important cogs in the replacement of workers in civilian employment.”

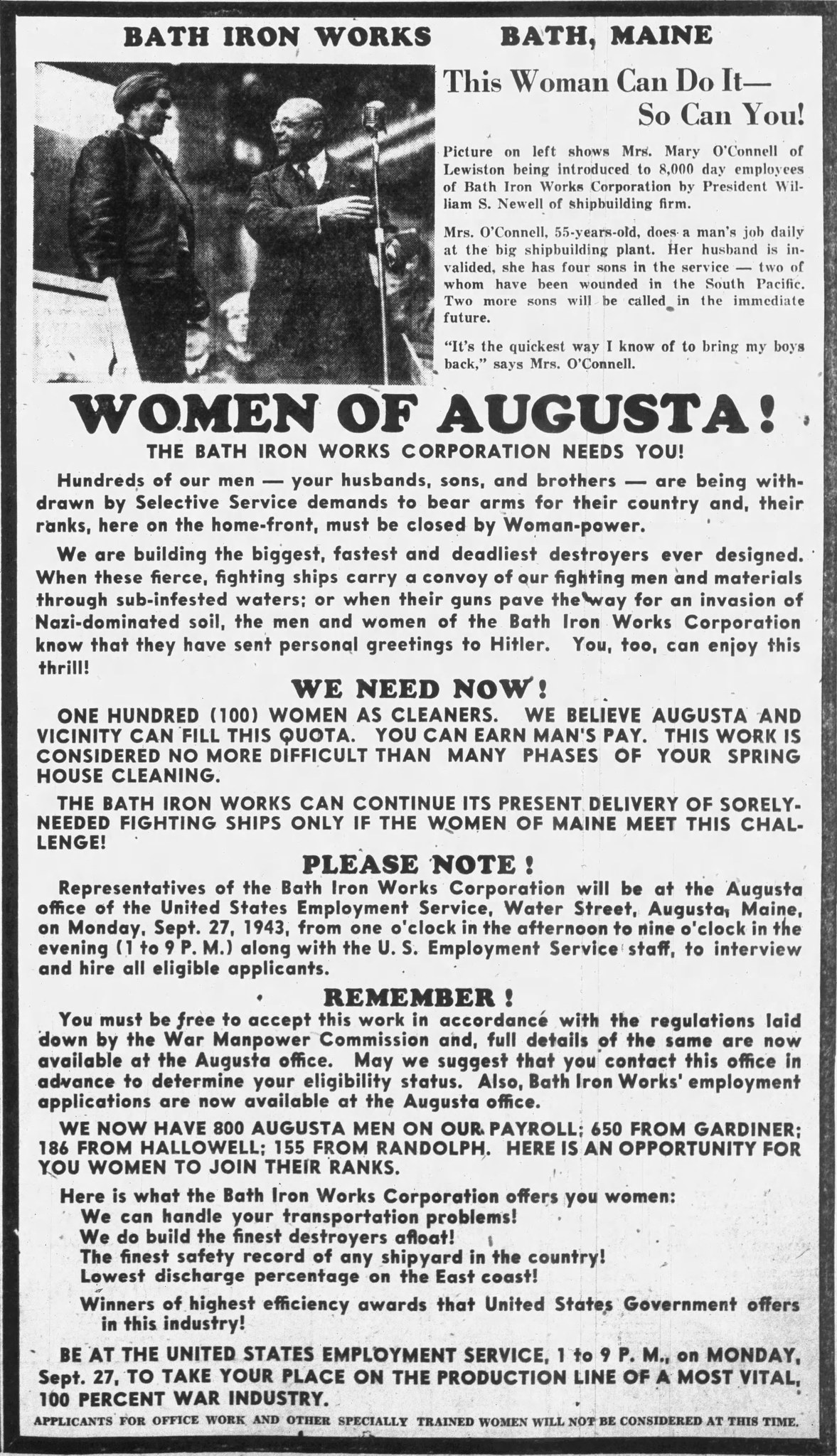

BIW recruitment ad targeting women workers. Circa 1940s.

Women were critical to building up the defense industry and Bath Iron Works went all over the state to recruit them for work in the shipyards.

"It is no military secret that during the coming year [1943] increasing numbers of women persons not now engaged in essential war work and handicapped persons must take their places on the civilian front,” the Lewiston Daily Sun reported.

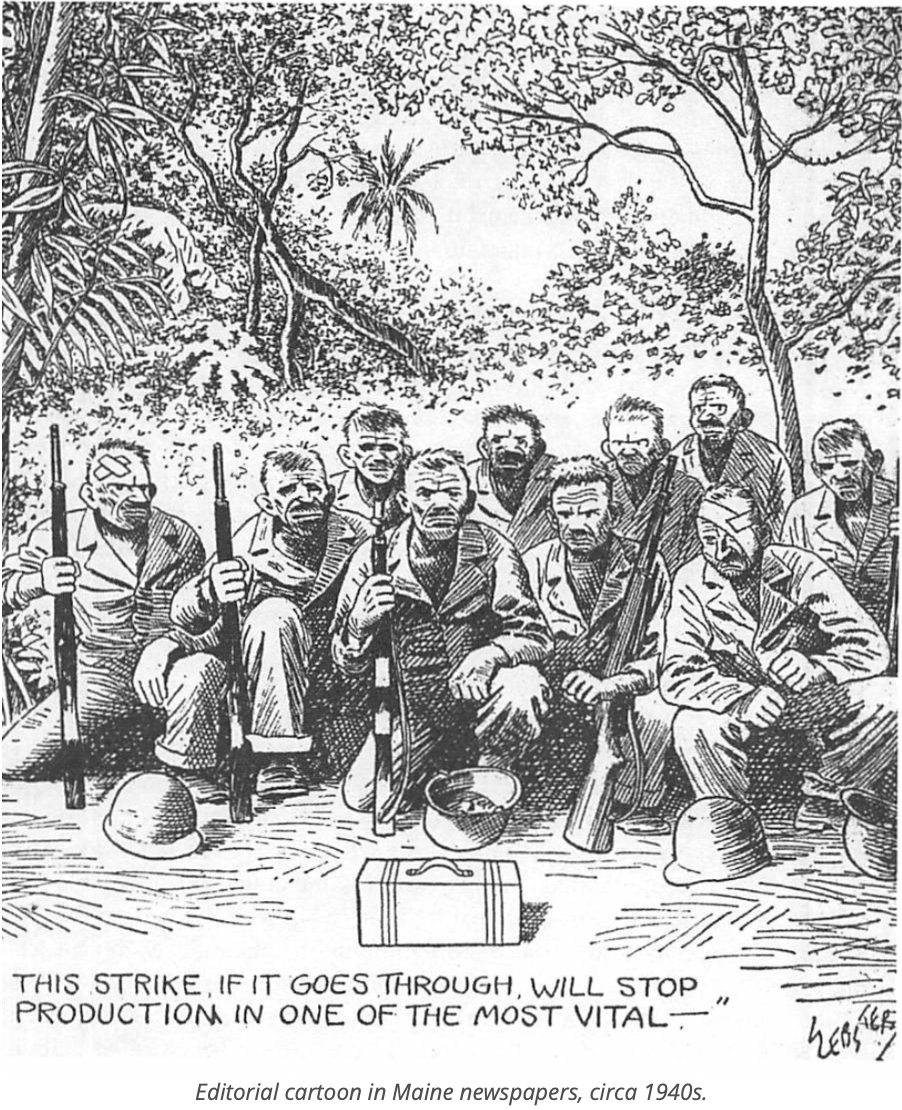

The theme of the 1942 Maine State Federation of Labor (MSFL-AFL) convention was “Patriotism” and delegates pledged to support a wartime “no strike” policy and full committed to "cooperation between industry and labor in the production of all defense materials and supplies.”

Furthermore, MSFL Vice-President Horace E. Howe announced that the AFL “will not tolerate communism, nazism [sic] or fascism within its ranks." He warned the convention delegates of Fifth columnists and “yellow men” who “extend the hand of fellowship and cooperation while the other hand holds the dagger.’”

"There is no room for any fifth columnists in the ranks of labor and wherever we find them in these organizations we should take the proper steps to get them out and put them where they belong,” he proclaimed.

Like during World War I, the MSFL Executive Board called on unions to set up committees to investigate “subversive elements and activities” and to urge all non-citizen workers to become naturalized. The Maine State Labor News regularly printed the FBI's message: "If you See a Saboteur or Spy please Call the FBI COLLECT, Augusta, Maine 0280 Liberty, Boston 5533.”

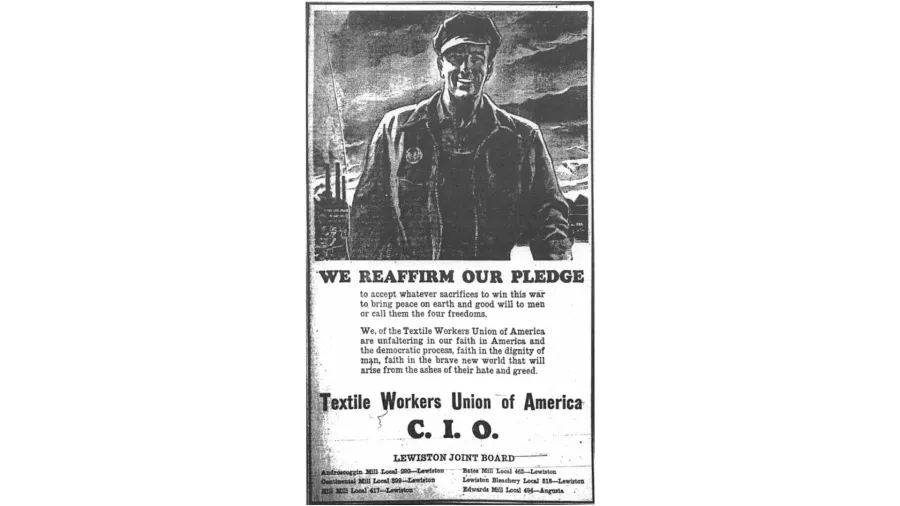

George Jabar, the Maine State Director of the Textile Workers Union of America (TWUA), CIO, echoed patriotic calls for workers to get behind the war effort.

“We laboring people realize that we live under the greatest government of the world. We know what has happened across the waters,” he told members. “There are no unions in Germany, Italy and Japan. Only in this country do we have the right to organize freely and to bargain collectively ... our only ism must be Americanism ... no sacrifice can be too great so long as our flag may wave and freedom reign.’”

The Bureau of Public Relations of the War Department provided Maine unions with a list of War Department films for viewing such as The Army Behind the Army, which promoted the critical role of workers in supporting US troops on the frontlines. In the shipyards workers repeated the “Shipbuilder’s Creed," stating that they would not miss a day of work and “every extra day off is a red letter day for the enemy!”

“I solemnly pledge to devote every working moment to the task given me by the United Fighting Forces,” went the “Shipworkers’ Pledge.” “I pledge to extend my effort to do my job well, so that I may never have it on my conscience that I caused one soldier, sailor, marine, or coast guardsman to die.”

As Maine labor historian Charlie Scontras Scontras observed, the war effort highlighted “the indispensable role of labor in the production process and the winning of the war, and by doing so reinforced workers’ claim to their historic role as the ‘producers' of wealth.”

Next week: The rise of the CIO in the South Portland shipyards