Labor History: How the National Labor Relations Act Jumpstarted the Labor Movement in Maine

Prior to passage of National Labor Relations Act, known colloquially as the “Wagner Act,” in 1935, there was no mechanism in federal law to govern union elections and require employers to bargain in good faith. There also weren’t any protections from employer retaliation for organizing, so workers were often afraid of being fired for joining unions. While membership in Maine’s textile unions had exploded to 3500 during the general strike of 1934, it plummeted to just 2000 members after the Supreme Court effectively took away their collectively bargaining rights in a ruling striking down portions of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s National Industrial Recovery Act the following spring. By 1937, the only United Textile Workers of America locals left in Maine were in Waterville, Madison, Brunswick, Fairfield and Pittsfield.

But the passage of NY Democratic Senator Robert Wagner’s National Relations Act in May, 1935 dramatically changed the game. The law created a new agency, the National Labor Relations Board, to enforce employee rights. It gave workers the right to form and join unions and required employers to bargain collectively with unions selected by a majority of workers in a bargaining unit.

“Oh boy, that was needed,” recalled UTW organizer George Jabar in a 1972 interview. “It was like a shot in the arm. You just went in, you gone up, you sign cards, and then you went along and you got, you started getting agreements.”

Following the election of Ben Dorsky to the presidency of the MSFL in 1937, he boasted that “thousands of organized textile workers had contributed to the growth of organized labor in the state and contributed to the growing success” of the federation. However, a bitter factional feud at the national level between the insurgent pro-industrial unions of the Congress of Industrial Organizations and the conservative, entrenched leadership of the craft-oriented American Federation of Labor would soon split the movement in Maine.

After the CIO’s first iteration, the Committee of Industrial Organizations, was formed in 1935 following a physical confrontation at the AFL’s convention, AFL leadership refused to recognize the upstart industrial organizing committee and demanded that it dissolve. Jabar attended the UTW’s 1936 convention where it endorsed the CIO and helped form the organization’s Textile Workers Organizing Committee (TWOC) a year later. After the CIO was officially expelled from the AFL in 1937, Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America President Sidney Hillman provided the funds for TWOC to hire organizers throughout the northeast. The merged unions in TWOC formed the Textile Workers Union of America (TWUA) in 1939. Prior to its formation, Jabar had been the only full-time organizer in Maine, but at his insistence, TWOC provided funding to hire three organizers, including a French speaker to organize the thousands of Franco-American textile workers.

Jabar had been placed in Holyoke, MA in 1937 because many textile workers still associated him with their embarrassing defeat during the strike of 1934. However, the new TWOC state director had failed to organize any new locals in the two years since he was hired. Union leaders realized that Jabar knew the terrain much better and called him back to the previous director in 1939. After meeting with national leaders in Waterville to map out their organizing plan, Jabar got right to work helping Madison Woolen Mill workers land their first collective bargaining agreement.

Prior to passage of the Wagner Act, none of the textile unions in Maine had contracts. Soon textile workers with TWUA began negotiating contracts at more mills, gaining for the first time union security agreements to have dues taken out of workers’ paychecks to pay the cost of collective bargaining. Jabar called the dues check-off provision “the guts of the labor movement” because it ensured everyone paid their fair share for representation. That’s also why corporations and their anti-labor allies in Congress rammed through the Taft-Hartley Act of 1947 which gut the NLRB and allowed states to pass right-to-work laws to make those union security clauses illegal. Prior to passage of the Taft-Hartley Act, Jabar noted that the NLRB required employers to remain neutral during union organizing campaigns, so workers didn’t have to endure captive audience meetings that are so successful in pressuring workers to vote against unions. It wasn’t until 2023 that Maine passed a law allowing workers to opt out of captive audience meetings.

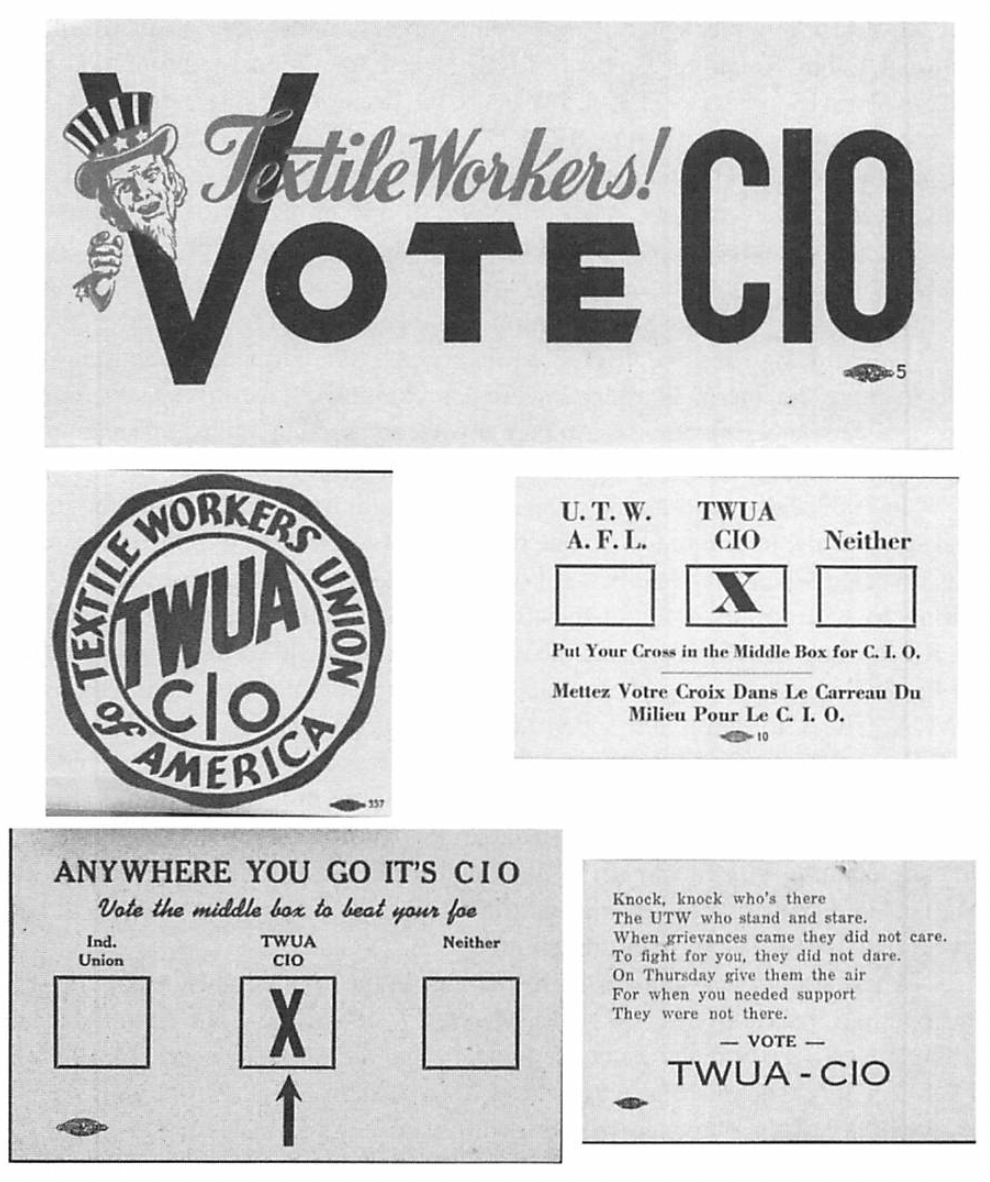

TWUA campaign literature.

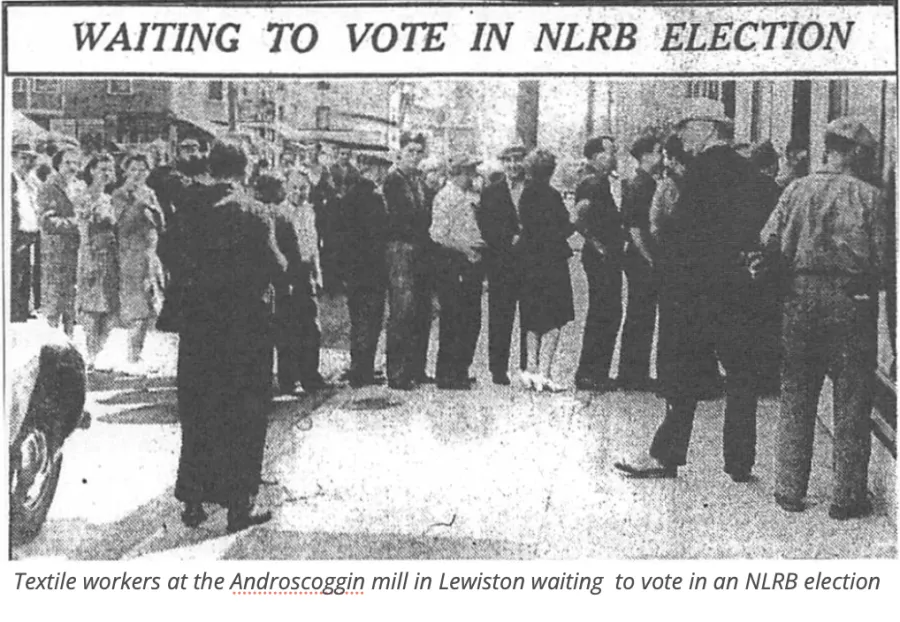

When the Wagner Act was at its strongest in the late 1930s and early 40s, it sparked a flurry of union organizing in Maine. As Jabar recalled, CIO organizers travelled from mill to mill across the state “knocking 'em off like flies” as workers signed up en masse to join the union. These days getting a super majority of workers to sign union cards is the gold standard for union organizing, but in the late 1930s, TWUA would typically file for an election after signing up just 10 percent of the workers. And they usually won.

In 1940, TWUA unionized Biddeford’s Pepperell Mill, which became the first textile mill in Maine organized under the NLRB. From their the dominoes began falling as locals organized at the Bates, Hill, Bleachery and Continental mills in Lewiston; the Edwards in Augusta, the Saco-Lowell shops and the York Manufacturing Company in Biddeford/Saco and nearly all of the American Woolen mills across the state. They also prevailed in contested elections over UTW locals who stayed with the AFL in Fairfield and Old Town.

Workers at the Abbot Mill in Dexter and Vassalboro opted to stay with the AFL, which Jabar attributed to lingering resentment over the 1934 strike. Still, the AFL-affiliated UTW was a shadow of its former self and had few resources to organize. It would continue on in a much diminished state until 1996, when it merged with the United Food and Commercial Workers. The new TWUA union had much more resources and its contracts provided workers with better wages, their first paid holidays and eventually health insurance plans.

The textile union drives marked the first in a series of battles between the CIO and the AFL in Maine as UTW distributed leaflets branding Jabar and the CIO as “Communists,” even though nothing could be further from the truth. Jabar was a New Deal Democrat and CIO President John Lewis was a Republican who support President FDR’s GOP opponent Wendell Willkie in the election of 1940.

Jabar attributed the massive success of TWUA in the 1940s to strong union leadership, proper funding for union organizing and passage of the Wagner Act. He said TWUA had also learned from the “debacle in Lewiston” when a CIO shoe workers strike was violently put down by police and National Guard Troops in 1937.

“The shoe strike gave us a lesson,” said Jabar. “When we approached it, we didn’t go right off, bang, bing, bang. We took the National Labor Relations Act, went to election and went to get the waiver and get the best agreement. Whatever we got in those days, the first written agreement even just to recognize on paper was an improvement. It isn’t like that today.”

Tune in next time for the Lewiston-Auburn Shoe Strike of 1937!