IBEW 2144 Member Dean Gilbert Recalls 40 Years at the Rumford Mill

IBEW 2144 member Dean Gilbert has officially retired after over 40 years working at the Rumford paper mill. Deano, as he is known to his friends and co-workers, is a dedicated union man who has long championed workers’ rights both inside and outside the mill. An avid skier and musician, Gilbert says he is looking forward to hitting the slopes and playing some music in his band D-No & the Full Send in his retirement.

“One thing the labor movement can tout is that if you pay your dues and you do your time, when you get done there are some rewards for that,” he said.

A third generation mill worker, Gilbert first began working at the mill as a helper during the summer after high school graduation in 1981. He had originally planned to study electrical engineering at the University of Maine, but he was making good money in the wood room “dodging logs and rats.”

“At the time, having an 18-year old brain, I convinced myself that I should not go and become an electrical engineer because I was killing it in Rumford making $4 an hour cleaning conveyor belts,” said Gilbert.

Every forty years, there’s a big turnover in the workforce at the mill and in the early 1980s all of the old World War II veterans were retiring so the company needed to fill hundreds of positions. Gilbert was offered a job as a permanent employee so he stayed at the mill instead of going off the college. He was eventually promoted to work on the Number 5 paper machine, the flagship machine of the Rumford mill.

“It was very prestigious to get on that. I was the lowest guy and the top machine tender on my shift was my father,” he recalled. “My dad’s main goal was to make sure that there was no favoritism shown toward siblings. I learned a lot under his regime for sure.”

But there were dark skies on the horizon. It a was time when paper companies were being bought up by Wall Street firms more interested in ringing profits out of the mills than the community or making a quality product. Emboldened by President Ronald Reagan’s firing of unionized air traffic controllers in 1981, corporations across Maine and the nation were prepared to wage war on unions.

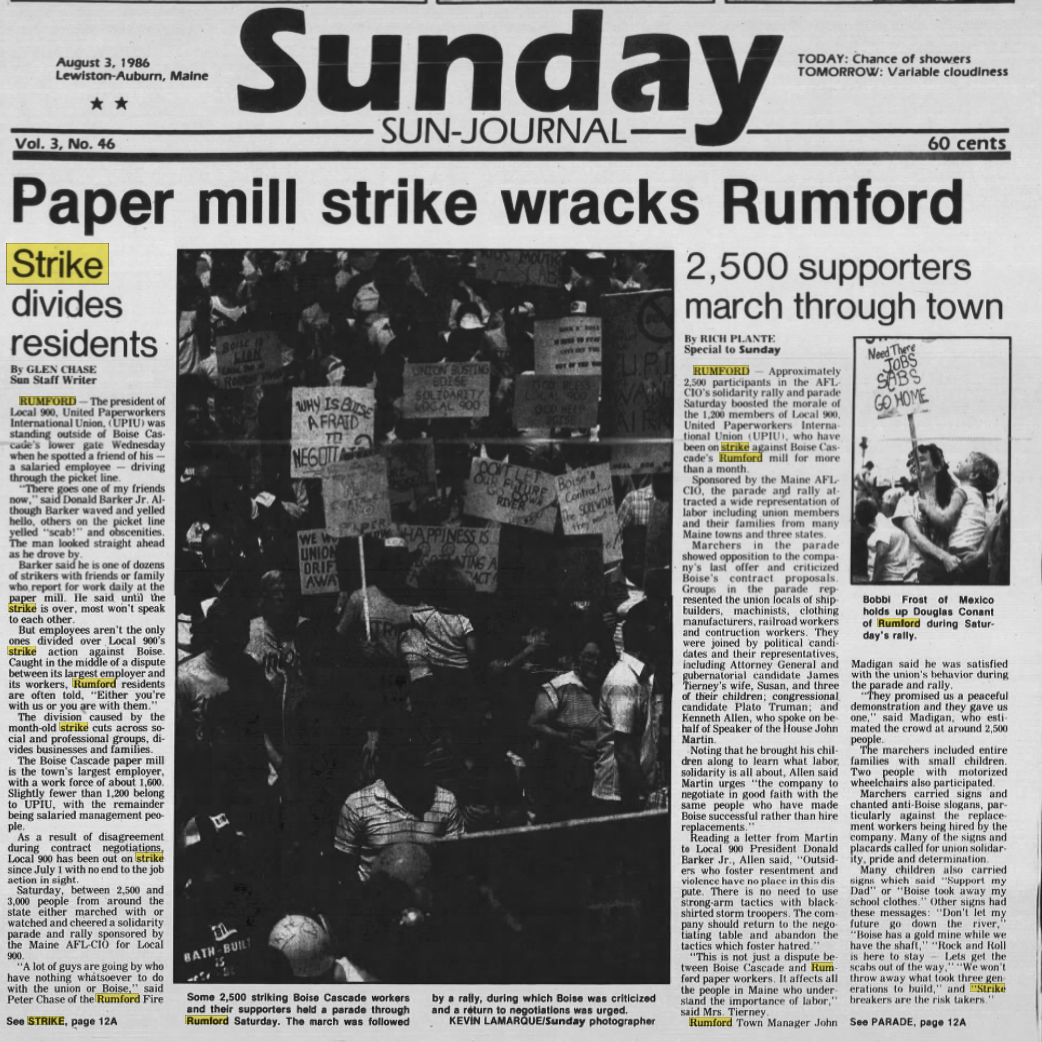

In July, 1980, 1,200 workers at the Rumford Mill went out on strike over then-owner Boise-Cascade's subpar wage and benefit package. But that was a mere prelude to the explosive strike of 1986.

That was the year Boise Cascade attacked the worker's core trades by demanding that skilled tradesmen fill in wherever they wanted them to work in the mill with no regard to their job descriptions. The workers said "enough is enough."

“You had Boise-Cascade come in with extremely deep pockets and they targeted the Rumford Mill because it was an out-of-bounds mill,” said Gilbert. “We had tin knockers, riggers, welders, painters, bricklayers and they wanted to come and say ‘if you’re a millwright, you can do anything. You can weld, you can paint, you can rig' and there was a huge pushback on that. But Boise came in guns a-blazing with a lot of money and were well organized.”

Gilbert said "no one saw the enormity of the pendulum” that was coming for them. Kerri Arsenault, author of the book Mill Town, remembered how horns blared for hours in town on the night union members walked off the job and drove laps around the mill’s gate “blaring their grievances.” Her father, who worked the 3 to 7 shift, sat with his friends in folding chairs drinking “coffee that tasted like it had been brewed with twigs that dropped from the beds of logging trucks,” in front of Dick’s Restaurant. The diner “vibrated with the broody rumble of the temporarily unemployed.” And then the company brought in the scabs.

“The strikers fought for their rights and eventually fought each other. It was scab versus non-scab; you sided with the Union or else. Picketers howled at logging trucks and banged on the hoods of scabs’ cars as their vehicles slithered through the mill’s main gates. People vandalized homes. Neighbors fought toe-to-toe. Cars got keyed. Heads were bashed. A roustabout even fired gunshots. At night, men and women gathered at the unofficial strike headquarters, The Hotel, for beer and blackballing super scabs, a special designation given to millworkers who went on strike and returned to work during the strike, but in someone else’s job.”

Gilbert gets choked up when he recalls that period. Thirteen weeks into the strike, the company fired 342 strikers and permanently replaced them.

“There were brothers who crossed with brothers who stayed on strike. It was unreal the amount of pain you saw in that area. It really ripped the town apart,” he said. “Then we watched the same thing happen 20 miles down the river in Jay in 1987.”

“That was 1986 and to this day, I can walk through the mill and see a guy who crossed the line and have someone ask, ‘That guy is a scab, right?’ That’s more than 30 years later.”

Gilbert recalled how union members would pack the local gymnasium for informational meetings during the Jay strike.

“Someone’s spouse would stand up and say ‘They can’t do this. My husband is irreplaceable,’” he said. “The lesson that we learned is that everyone can be replaced and they had no problem with doing that.”

In the aftermath of the strike the Ku Klux Klan came to Rumford to hold a rally in an effort to capitalize on the lingering bitter feelings from the strike. An anti-Klan rally held at a school auditorium drew about 300 protesters. Although the Klan rally was tiny, it was a stark reminder of how wealthy elites and their white supremacist allies use racism and xenophobia to divide the working class in America because worker solidarity threatens their economic interests. It took a few years, but eventually the fired strikers were hired back.

Meanwhile, Gilbert used the time off to look for other career opportunities. Besides the mill, there weren’t many options in the area aside from construction or working in a retail store. He decided to pursue an apprenticeship to train in electrical and instrumentation (E&I). His father wasn’t pleased that his son was switching to the IBEW local, but years later he told him it was the right decision in hindsight.

These days, Gilbert says his job has become much harder due to understaffing. Workers are frequently drafted to work much longer days and come in on their off days. He said he used to think he had the “coolest job ever,” but by the end he was burned out.

“I was planning to work an extra year, but with the new bosses in there, they just don’t care about your home life. I just figured if I can get out now I’m going to get out,” said Gilbert. “I work with a lot of people who are awesome and there are really good folks in the mill, but you can just see in our industry, it’s a little harder to hold a job down. You’re away for longer than ever. It’s all profit, profit, profit.”

He said it’s hard to attract people to work in the mill when workers have other options. Back in the 1980s, every time the mill had a job fair there were 1000 applicants lined up and down Congress Street to sign up, but now the mill struggles to find qualified applicants. He’s observed that younger workers want to have a better work-life balance and often leave after a few weeks of doing shift work in a hot paper mill.

He says his favorite memory with the labor movement is the euphoria he felt with his union brothers and sisters as hundreds of them filled the State House in 2011 and killed the notorious right-to-work for less bill. He says young workers need more role models who go the extra mile and volunteer their labor to improve conditions for all workers.

“For a lot of us, it’s not about the cash when you take these jobs [in the union]. It’s about the history and knowing you’re working past guys who you’ve idolized. I was always told ‘do what you can, but if you can leave it better than it was, you won.’”