How Calais Nurses Won the First All Professional Hospital Union in Maine

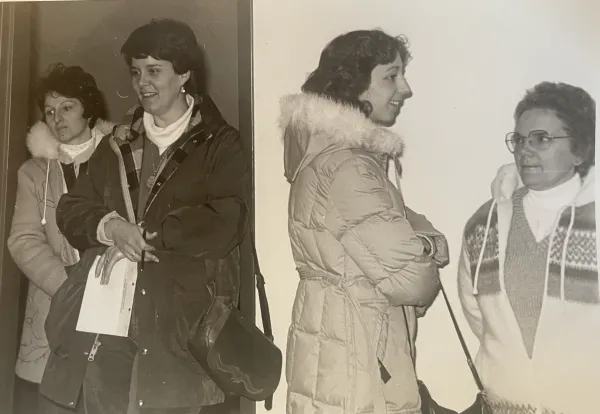

(L-R) Calais nurses Kathy Day, Joyce Nixon, Cindy Whalen, Debbie Wheaton, Karen Thomas & Gloria Hollingdale celebrate their union election win on January 16, 1985. Courtesy Gloria Hollingdale.

The Maine Hospital Association was petrified that the ratification of the first hospital contract in Maine by Eastern Maine Medical Center nurses in 1981 would set off an organizing wave across the state. That’s kind of what happened, but it didn’t play out the way MSNA nurses hoped it would when they passed a strong resolution to organize the state’s 5,000 registered nurses the year before. Instead of winning victories at the other large hospitals in Portland and Lewiston, the majority of successful union drives were in much smaller, rural health care centers in central and Downeast Maine.

Former MSNA organizer Polly Campbell said part of the challenge in organizing the larger hospitals was that there was so much staff turn-over that it was hard to get a core group of nurses together to form an organizing committee. But the biggest barrier was a 1983 ruling by President Ronald Reagan’s National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) that required nurse bargaining units in hospitals to also include positions like lab technicians, pharmacists and other health care workers. Non-nurses resisted being lumped in with nurses and typically voted against unionizing.

“They didn’t want to be part of a nurses’ union. That’s why we were losing elections,” said Campbell.

By allowing only three or four bargaining units at a hospital, unions had to prove that the interests of the different workers were so distinct that it justified additional units. Not surprisingly, the American Hospital Association strongly backed the ruling as it resulted in a sharp drop in the proportion of hospital workers belonging to unions.

As AFL-CIO attorney David Silberman explained to the NY Times in 1988, ’'The practical effect was that if a union tried to organize less than wall to wall, the employer would object and tie it up in the NLRB. The larger the group, the harder it is to organize, particularly when you have to cross different groups that have few common concerns.’'

But at Calais Regional Hospital, a group of determined nurses and their colleagues would buck the odds and form the first all-professional bargaining unit at a hospital in Maine in 1985. This is their story.

********

Gloria Hollingdale early in her nursing career.

Retired nurse Gloria Donahue Hollingdale of Calais, 91, grew up just across the border in the textile manufacturing hub of Milltown, New Brunswick.

“There were no cell phones or internet back then,” she said. “Mothers got their news at the clothes lines. They washed every Monday or Tuesday.”

Her father was a loom fixer and a proud union man who worked at St. Croix Cottons, which employed 1000 people in its heyday of the 1940s and 50s. Hollingdale remembered when her father and his coworkers formed their union at the mill and when he was elected to the union's board. He instilled in her a respect for unions from a young age.

“My father was a Donahue, a good Irish name of a lot of union people. He was very laid back, very genuine, very people oriented,” Hollingdale recalled.

When it came time for Hollingdale to decide what to do for a career in the early 1950s, she decided to attend Mercy Hospital’s nurse training program in Portland because it had a strong reputation. After she graduated in 1954, she returned home to Milltown and met her husband, an American boy from Calais.

“Border town living is different than any place else,” she said. “The American boys would go over to Canada to get their girls. There are a lot of Canadian wives over here who married American boys.”

She worked on the Canada side for a few years until she and her husband decided to start a family. They lived in Calais and she got a part-time job at Calais Regional Hospital (CRH) in 1964. Like many nurses of young children back then, she worked on weekends while her husband watched the children. She first worked in the maternity ward.

“I had a week’s orientation and then I was on my own. I mean terrible things could happen. It wasn’t safe at all,” she said.

One day she had a patient in for delivery and called the doctor for assistance. He was out on the golf course and called back to tell her not to call until she saw the top off the head. It was the woman’s fifth child, so he wasn’t concerned.

“He said, ‘oh the fifth child. She’ll just push that right out. I won’t even need to be there hardly,’” Hollingdale recalled. “Then he put the receiver down and I had to deliver that baby with the help of the supervisor. He did come after the baby was born."

Other times, nurses had too many patients to care for safely at once.

"Usually, you didn’t get too many through the night like on the weekends, but you really did at times and it really wasn’t safe,” she said. “We wouldn’t even get home and the phone would ring and we’d have to go back. You would ask for more help, but of course in the nursing office they thought they knew more than the nurses on the floor about what was going on, which they didn’t.”

Other times, Hollingdale and her colleagues were forced to get down on their hands and knees to pick up used syringes and other medical waste the surgeons threw on the floor. She recalled being directed to go to the medical-surgical unit right after finishing up in the operating room, when on call, to find several of the most difficult patients.She had not seen those patients she was assigned so she had to consult the Physicians' Desk Reference (PDR) to look up the drugs she needed to administer. They never used those drugs in surgery and what drugs they used were administered by an anesthetist.

“It was very, very dangerous going out on those floors,” she said.

The one time in her career that she filed a report about unsafe working conditions was when she had seven patients whom she had never cared for. One of them was a two-year old child with croup, which can be life threatening for young children. While she was setting up a croup tent for the child, a woman came in complaining that her father had not had a bath yet.

“She was going to report me and I was trying to keep this little baby alive. Five other patients I hadn’t even seen yet,” said Hollingdale. “Well, I had just had it. I thought this is so dangerous. That baby could die. That heart patient could have another heart attack or something and the other people were ringing the bell.”

But when she asked her supervisor for more help, she was denied assistance, so she had to file a complaint.

“That’s when I thought, ‘I’ve got to do something. I can’t be in this situation again. Something bad could happen,” said Hollingdale. “The supervisor at the time was a friend of mine and I hated to do it, but I had to. I was just at my wit’s end.”

In response, the hospital did make some changes to ensure nurses received better orientation before going out on the floor, but other problems persisted. Job security became one of the biggest concerns for nurses at CRH.

“Girls who were pregnant would go out on maternity leave and they had about six weeks, which wasn’t a lot of time,” said Hollingdale. “And when the nurses came back, especially one I remember in the emergency room, she no longer had a job.”

Often the hospital would replace nurses out on maternity leave with Canadian nurses who lived across the border in New Brunswick where there weren’t many nursing jobs available. This created a lot of resentment among the American nurses. The Canadian nurses weren’t interested in immigrating to the US because they didn’t want to lose their Canadian national health insurance, she said.

“They got all the jobs that they wanted and the American girls were out of a job,” said Hollingdale. “There were little rumblings about a union then and that probably was the biggest thing happening because there were five or six Canadian girls who got full-time jobs.”

One of the reasons there wasn’t a nurse shortage in Canada, said Hollingdale, is because nurses were paid much more than American nurses and they still are. The money also went further over the border in Canada due to the exchange rate. RNs suspected that CRH paid the Canadian nurses more than the American nurses because their supervisors always told them not to share salary information with each other. Prior to forming their union, the Calais nurses brought their concerns to the hospital administrator Ray Davis, who said he would address them. And then he didn’t get back to them for several months.

“Six months later we talked again and there wasn’t any change so that’s when we called the Maine State Nurses Association,” said Hollingdale. “We figured we went through the director of nurses and we went through the CEO so we knew we weren’t going to get any help and that was our recourse.”

It was a young nurse from Millinocket named Kathy Day who really kickstarted the campaign, according to Hollingdale.

Kathy Day supporting Eastern Maine Medical Center nurses on the picket line in 2010.

“Kathy Day was the one who is really responsible for our union,” she said. “She wasn’t local so she didn’t have to worry about knowing everybody in town and people taking sides and that sort of thing. She was our savior.”

Kathy Day started her career at Millinocket Regional Hospital when she was just out of nursing school in the 1970s. Like Hollingdale, her father was a union man and worked at Great Northern Paper like many men in town at the time. It was before a union formed at Millinocket, but she did end up working as a per diem nurse at Eastern Maine Medical Center where she voted for the union there in 1976.

But in 1978, her husband took a job for US Customs in Vermont, so she ended up leaving Bangor. After a stint in Montreal, her husband got transferred to Calais in 1982 and she started working as a per diem nurse at CRH the following year. Day was struck by how chronically short-staffed the hospital was at that time. At the time there were about 50 nurses at CRH covering three shifts.

“One night I was asked to work and I would be the only nurse in the whole hospital. And I did it because there wouldn't be another nurse there if I didn’t do it,” she recalled.

Conditions had gotten so bad that Day suggested to Hollingdale that they explore forming a union.

"My first impression was how amazing the nurses were there and how hard they worked,” said Day. “I was just blown away by the dedication and skills of the nurses in Calais. I met some incredible people there and we all hated the way they were being treated.”

Hollingdale greatly admired Day because she wasn’t afraid to speak her mind and she didn’t worry what other people in the community thought of her. She was seen as an outsider.

“I envied Kathy being able to speak out,” said Hollingdale. “What we didn’t dare say, she would.”

Day reached out to her contacts at the Maine State Nurses Association and it wasn’t long before MSNA’s Director of Economic and General Welfare Polly Campbell, Day and Hollingdale were meeting with nurses in their homes and at a local church to discuss organizing. As soon as the hospital caught wind of the effort, Day had a target on her back.

“We were considered evil,” said Day. “I was friends with some managers and there were some really weird stories floating around about me that I was planted there because I initiated the campaign but I had a lot of help leading it.”

When the nurses submitted their union petition, CRH challenged the composition of the bargaining unit and requested that other professional employees be included. Hearings continued into the spring of 1983. Although the election was held that June, the ballots were impounded by the NLRB pending a decision on the composition of the unit. Finally in Dec. 1984 the Board ruled in favor of an All Professional Bargaining Unit and a new election was held. Eligible voters included 50 professional employees comprising RNs, staff pharmacists, social workers, alcoholism councilors, certified nurse anesthetists, physicians assistants and medical lab technologists.

The Hospital's Anti-Union Campaign

Ray Davis (far left) with Gov. John Baldacci at a hospital ribbon cutting in 2006. Courtesy of CRH.

The hospital hired the anti-union law firm Skoler, Abbott and Hayes out of Boston and paid an attorney $1000 a day to defeat the union.

“Every week, Ray Davis the administrator hit up all of the employees at different times, but he made sure to hit all of them up in the solarium where he would put down unions,” said Hollingdale. “They waged a big anti-union campaign and threatened us that if we were caught talking about the union on hospital time we could be fired."

A few of the 150 hospital employees who were ineligible to vote in the election even circulated a petition and presented it to the 50 eligible voters prior to the election, informing them that they opposed the union because they believed it would harm patient care.

The Election

(L-R) RNs Mary McLellan, Kathy Day, Karen Thomas & Edna McLellan await the results of the election. Courtesy Gloria Hollingdale.

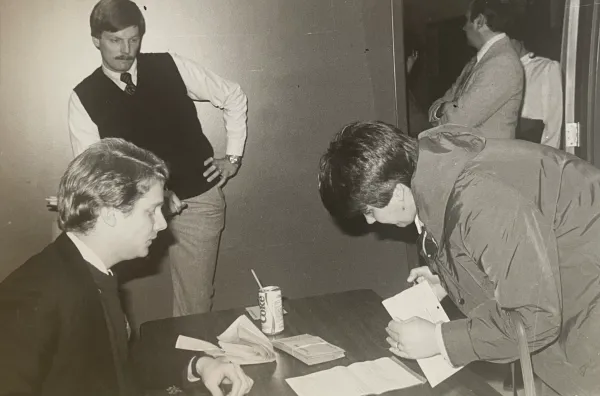

NLRB staffer is seated while Kathy Day signs documents and hospital attorney John Glenn stands by. Courtesy Gloria Hollingdale.

A new election was held on January 16, 1985 and when the ballots were finally counted the $1000 per-hour anti-union lawyer from Boston proved to be no match for a group of tough Maine nurses. The union side won on a vote of 26-15 to become the first all-professional health care workers unit in the state of Maine. They were now part of a growing MSNA family that included nurses at EMMC, Millinocket, Mount Desert Island in Bar Harbor, American Red Cross Blood Services in Portland and Bangor and Monadnock Hospital in Peterborough, NH.

“Our vote reaffirms our commitment to the quality of patient care at Calais Regional Hospital. We organized because we knew a Collective Bargaining Agreement was the only way we would have input into our practice in the first step in improving patient care at Calais Regional Hospital,” said Gloria Hollingdale, the new MSNA Local 3 President in a statement following the vote. “The hospital management has tried, through delays, and other tactics to keep the union out of Calais Regional Hospital. Management thought that forcing other professionals into the bargaining unit would dilute our strength. The hospital’s tactics have backfired… instead of a union of registered nurses, now, all of the professionals are unionized. The nurses see this as a positive step toward unifying all employees within the hospital and look forward to contract negotiations.”

Hollingdale credited the win to the solidarity among hospital workers across different departments.

“We’re in a small community so everybody in hospital knew everybody else,” she told Maine State Labor News in an interview recently. "We knew everybody and had friends in every department, so I wasn’t too worried, but you never know what people are going to do when they’re in the voting booth.”

Day remembered a lot of negativity and how antagonistic it was between pro-union and anti-union nurses. But in the end she thinks several of the quieter ones came around to see the benefits of unionizing.

“They came to meetings, they just didn’t know if it was the right thing to do, but I think they appreciated that we got the union in the end,” she said.

Ray Davis told the press he accepted the results of the election and said he looked forward to negotiations. However, the hospital made sure Day paid the price for her organizing work. She stopped getting calls for per diem work in a blatant act of retaliation. Instead, an LPN was given work that Day would have done normally. After the union filed an unfair labor practice complaint, one of Day’s supervisors testified that she was instructed not to give her any work.

“The hospital claimed that my employment had ended, but it was the first I knew of it. I hadn’t quit. Nobody told me I was fired so that was a lie and that didn’t fare well for them,” Day said.

The NLRB ruled in favor of Day, but did not award her back wages because she had been per diem. By that time, she had moved on to mostly working as a nurse at the local paper mill and the Passamaquoddy reservation.

“The [ULP] win was more symbolic than anything,” she said. “It was a warning to them though not to do that to other people who were in the union.”

Hollingdale led negotiations for the Calais nurses’ first contract. The other RNs figured she wouldn’t be harassed by management as much because she worked “behind closed doors” in the operating room, but just the opposite happened.

“The director of nursing and the assistant director were in the recovery room three or four times a day while I’d be working to see if they could catch me doing something I guess,” she said. “They really badgered me but it was worth it in the long run.”

The Calais nurses finally won the job security they were seeking at the bargaining table. They also won better pay, union protections, a grievance procedure, seniority rights, improved staffing and more. In 1988, the NLRB expanded the number of bargaining unit categories, allowing for all-nurse unions again.

Hollingdale went on to lead the union for many years before finally retiring in1994. Day ended up moving back to Bangor with her family and worked a number of nursing jobs at Eastern Maine Medical Center where she was an active union member. She retired from nursing in 2000 to help raise her granddaughter, but became more involved in politics after her father died in 2010 of a hospital acquired infection called Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA).

After researching the issue, she enlisted the help of her State Rep. Adam Goode (who is now the Maine AFL-CIO’s legislative and political director) to sponsor legislation to protect patients from MRSA infections. She reconnected with MSNA and the union testified in support of the bill. A watered-down version of the bill passed that only covered certain groups of patients. She went back to the Legislature the following year with a stronger bill, but it didn’t pass unfortunately. She is still involved in a group called Patient Safety Action Network that advocates on the state and federal level.

“People say why don’t you run for office? And I say because I’d be too ugly all the time,” Day said laughing.

Day and Hollingdale acknowledge that some of the battles they fought are still ongoing, like the safe nurse-patient staffing crisis.

It’s just a chronic issue with nurses and nursing,” said Day. “It has to be remedied or we’re going to lose the profession. I sincerely feel that way, especially since covid and the scary business that nurses had to deal with, like by having insufficient protective gear and inadequate staffing.”

The two retired nurses still reminisce about their struggle to form their union at Calais Regional Hospital. They talk about the lifelong friendships they made at the hospital and their colleagues who have since departed. Day says a strong bond was formed between the RNs as they united in their struggle for better working conditions and patient care.

“I think what we gained from that experience was our respect and love for each other,” said Day. “We all wanted what was best for our patients, but we also wanted what was best for us. We didn’t want our licenses endangered because we didn’t have enough nurses to work. We didn’t want to be forced to work in a department we knew nothing about. I hope to God the nurses there never let their union go.”

Hollingdale says her advice to new nurses is to always “put the patient and their families first because behind every patient there’s a family.” She says she experienced this kind of care and compassion first hand while having an aortic valve repaired at EMMC last April.

“Those nurses couldn’t have been any nicer or compassionate,” she said. “It was a really wonderful experience and they made it that way.”