The History of Shipbuilding Unions: The AFL Strikes Back in ’42!

PHOTO: New England Shipyard. South Portland, Maine. 1943. From Left to right; Carmaleta Haley, Irene Howard, Ella Bartlett, Rowena Gardner, Reta Martin, Madelyn Gross, Frances Spaltro, Sally Warning, and Mildred Burrage (at the far right). Maine Historical Society

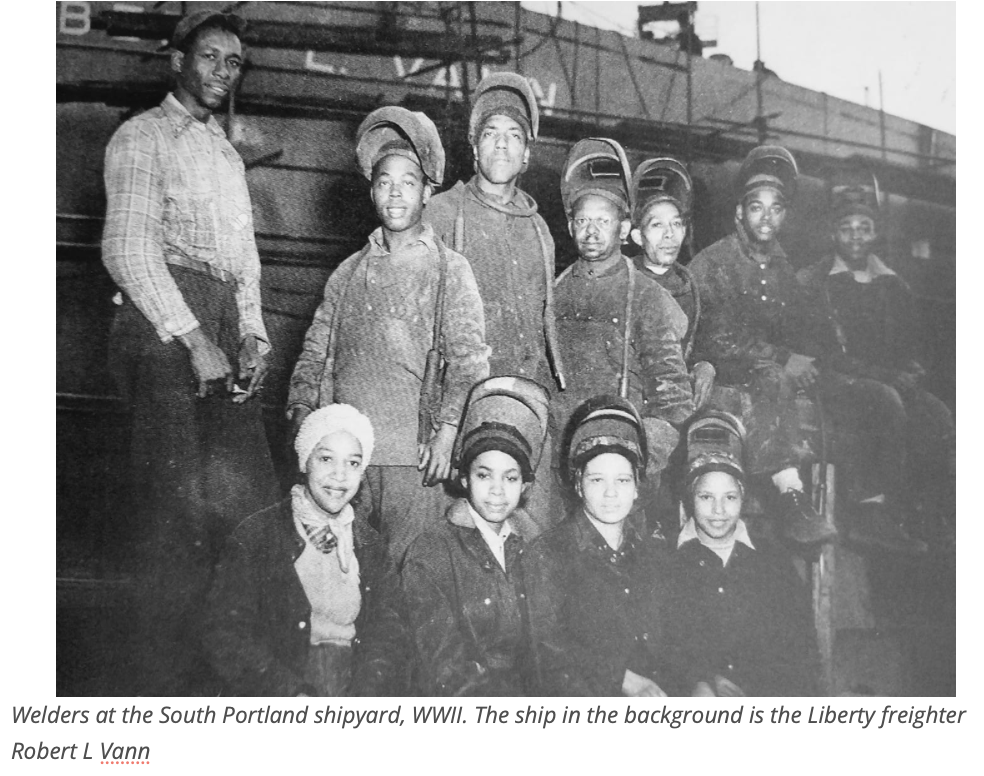

We are finally getting caught up on our series about the history of shipbuilding unions in Maine. Here is the next installment based on labor historian Charlie Scontras’ book "Labor in Maine: Building the Arsenal of Democracy and Resisting Reaction at Home, 1939-1952."

At the end of March, 1942, Maine shipyard workers with the CIO’s Industrial Union of Marine and Shipbuilding Workers (IUMSWA) at the Todd-Bath shipyard in South Portland were celebrating their landslide election victory over the more conservative American Federation of Labor and the Independent Brotherhood of Shipyard Workers, an unaffiliated, more company-friendly union that had organized Bath Iron Works shipbuilders in Bath the year before. However, their fight for union recognition wasn’t over in South Portland.

After President Roosevelt announced an Emergency Shipbuilding Program to produce 200 standard class cargo vessels, later known as “Liberty ships,” the U.S. Maritime Commission established the South Portland Shipbuilding Corporation to construct a new yard to the west of the Todd-Bath had their own union election in the spring 1942. It was a bitter struggle with both the AFL and the upstart CIO at each others’ throats while the plucky young Independent Brotherhood sought to recreate the magic that helped them win at BIW the year before.

The AFL drove a sound truck around South Portland and the neighborhoods of Lewiston, where as many as 3,000 shipyard workers lived, disparaging the CIO as a bunch of violent radicals.

"Remember what the CIO did to this town in the shoe strike," the AFL shouted from the loudspeakers.

It reminded Lewiston residents of the CIO’s disastrous 1937 Lewiston-Auburn shoe strike and how its failure cost workers several millions of dollars in wages and contracts that were never regained. Unlike the CIO, the voice boasted that the AFL had not had a strike since Pearl Harbor.

In its literature, the AFL characterized the CIO as “strangers at the gates” — Communist-led out-of-state agitators seeking to trick and take advantage of hard working, salt-of-the-earth Mainers. The AFL proudly boasted that it expelled anyone suspected of subversive activity. Extra copies of the Maine AFL's Maine State Labor News were circulated to shipyard workers with a front page editorial stating that Maine workers were too intelligent to join a union that “sponsors sit-down strikes and other un-American methods during controversies.” Such direct actions, MSLN argued, played right into the Nazis hands by hampering war production

“Ever since Pearl Harbor we have read of CIO strikes and threatened strikes,” wrote AFL women’s auxiliaries in the paper. “Some of them in the very industries producing the supplies so sorely needed by the gallant General MacArthur! Certainly, we women do not want any of that kind of action here in Portland. We are first Americans.

Were the workers of South Portland Shipyards, the AFL asked, "willing to tie themselves up with an organization that would kill and maim people because they refused to join in an association whose officials subscribe to a philosophy which is entirely foreign to our democratic way of thought and action?”

In the end, the AFL clobbered the CIO by a margin of 1,261 to 433 in the SPSC election. The Independent Brotherhood came in second with 511 votes. The AFL’s Metal Trades Department negotiated a new contract with a union security clause, paid vacations, shift differentials, cost of living adjustments, time and a half for working over 40 hours a week, double time on Sundays, dues checkoff and a grievance procedure. However, it failed to agree on wages due to disagreements over classifications and the rate system. The CIO attributed the breakdown in negotiations over wages to jurisdictional problems among various crafts as "warring organizers" bickered over which crafts were to perform certain tasks.

This was exactly the problem the CIO sought to avoid with its industrial union model that organized all of the production workers at a shipyard into one union rather than having separate unions for each individual craft. As Maine labor historian Charlie Scontras noted in his book Labor in Maine: Building the Arsenal of Democracy and Resisting Reaction at Home, 1939-1952, ship fitters, tackers, welders, and yard crews tended to support the CIO, while machinists and electricians supported the AFL. After IUMSWA, CIO won representation at the neighboring Todd-Bath shipyard, electricians refused to affiliate with the CIO because of the loss of AFL benefits. As a result, twelve electricians were discharged and six walked out. Rumors soon flew that other skilled workers — including carpenters, machinists, tinsmiths, and crane operators — would follow the lead of the electricians.

By the time the SPSC contract was ratified in July, 1942, the SPCC workforce had grown to 9,000 workers and expected to reach 12,000 by the end of the year. However, the battle between AFL supporters and pro-CIO workers was far from over. That spring, Todd-Bath’s East Yard and the SPSC’s West Yard merged to form the New England Shipbuilding Corp. (NESC) — the fifth largest emergency shipyard in the nation with 25,000 workers. With the IUMSWA -CIO representing workers in one yard and the other yard unionized with AFL’s Metal Trades, both unions claimed to represent the consolidated yard. The only way to resolve this jurisdictional quagmire was another NLRB election.

Tune in next week for the next installment of “The Spirit of the CIO: The Origin of Shipbuilding Unions in Maine.”

Read the first eight installments of our series covering the Origin of the Shipbuilders’ Unions in Maine:

- Part 1: 90 Years Later: Local S6 & the Spirit of the CIO Part 1

- Part 2: The First Union Formed at Bath Iron Works

- Part 3: Maine Workers & the March to World War II

- Part 4: Maine Workers Mobilize for Wartime Production in WWII

- Part 5: When "The Hicks Beat the City Slickers” in the BIW Union Election of 1941

- Part 6: When BIW Welders Launched a Wildcat Strike

- Part 7: Welders Continue to Wage Wartime Wild Cat Strikes

- Part 8: Organizing the South Portland Shipyards