A Higher Calling: Mike Seavey Discusses the Connection Between Faith & Labor

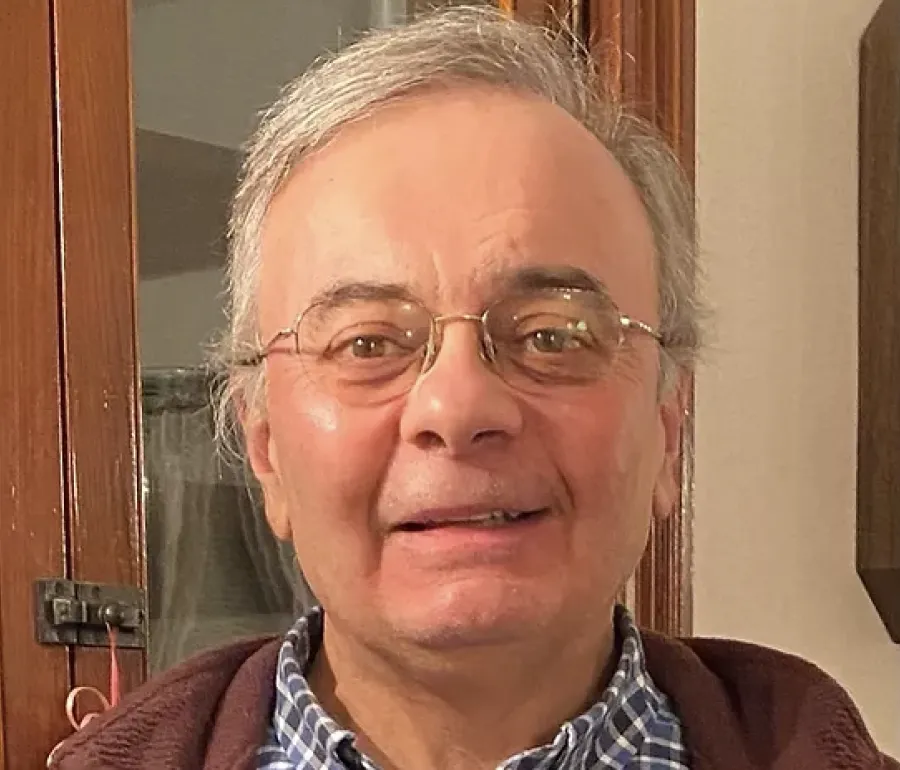

At our upcoming COPE Convention on June 23rd in Auburn, we will present Mike Seavey with our President’s Award for his years of work connecting labor and faith communities and making the moral case for workers' rights, unions and economic justice.

Known to many as “Father Mike,” Seavey was a Catholic parish priest for 35 years. Throughout his career he strived to incorporate the churches’ social justice teachings into his Biblical lessons and to advocate for workers, unions, immigrants and low-income communities. For many years, Seavey has performed benedictions at various labor events.

In January, 2020, Seavey requested a leave of absence from the priesthood and launched an initiative to recruit faith leaders to join the movement for workers’ rights. He is currently the volunteer Faith and Labor Liaison for the Maine AFL-CIO.

“I’m still in discernment and to be honest I’m still waiting for God to move in my life,” he says. “I’m just open to that and whatever that is.”

His passion for workers’ rights stems back to his childhood in Portland as the son of a union member. Seavey’s father was the president of his local union at the American Can Company, a now-defunct manufacturer in Portland. Union culture was baked into his parents’ social life as most of their high school friends all got jobs at union shops after graduation.

“When our families would get together, we’d play with their kids and my sister and I have been great friends with them ever since,” he said. “Our dads would be talking about their unions and what was going on and what they were doing.”

His father was very nurturing and patient with his children and he always had time to answer his curious son’s many questions about his work and his union. Once when Seavey was about six or seven, there was a major steel workers’ strike and he knew from his parents’ conversations that there was a chance his father would be laid off due to a potential shortage of materials. One day, his father came home announcing how proud he was that all but two of his members contributed money to the steel workers’ strike fund.

“I remember saying, ‘dad, why would you do that? You could get laid off,’” recalled Seavey. “He sat me down and he said, ‘Mickey, when you make a decision to stand up with somebody and you think they’re doing the right thing, you don’t sit down again just because you might get hurt.’ That was the way he talked about solidarity without using that word because I wouldn’t have known what they meant.”

One day, when his father showed up with a load of groceries, Seavey and sister complained that he had bought ginger snaps.

One day, when his father showed up with a load of groceries, Seavey and sister complained that he had bought ginger snaps.

“My sister and I said, ‘oh we don’t like ginger snaps. Those are cheap,’" recalled Seavey. "And my dad said, ‘well this might be all you have because I might be going out on strike and it’s all we can afford. So we said, ‘well, we won’t open those cookies until you go out on strike.’”

Fortunately, they never had to open them and after sitting in the pantry for a year they were eventually discarded. But from then on ginger snaps were known as “strike cookies” in the Seavey household.

When Seavey went to study for the priesthood, he had no knowledge of the Catholic Church’s social justice teachings and support for unions, but after learning about it in seminary his love for justice expressed through labor unions became a motivating factor in his life.

“It has always been part of the church’s light to care for and advocate for the poor,” he said. "When the church hierarchy loses touch with that or we become more corrupt or decadent, is when the church starts falling apart. When that happens, usually there’s a new religious order that emerges and starts taking care of the poor again and the church finds new life.”

For most of the 19th century, the Catholic church had little interest in supporting labor organizations even as business put profits above all else and working class Catholics were brutally exploited, maimed and even killed by the machinery of the Industrial Revolution. Since church leaders wouldn't advocate for them, Catholic workers in Europe began to leave the church and joined radical movements that were advocating for policies to help workers. Even as companies were using government troops and police to attack striking workers and crush strikes in the 1880s, Bishop James Healy of Maine, where an estimated 41 percent of workers belonged to the Knights of Labor, condemned the unionbecause he considered it too radical.

Then in 1891, Pope Leo XIII issued Rerum Novarum (Rights and Duties of Capital and Labor), a papal encyclical that decisively came down on the side of the workers and was scathingly critical of the plutocrats who had amassed tremendous wealth on the backs of workers during the Gilded Age. The Pope called for the amelioration of "the misery and wretchedness pressing so unjustly on the majority of the working class” and supported the right of workers to form unions. The encyclical also rejected both socialism and unfettered capitalism and affirmed the right to private property.

In the first half of the 20th century, church leaders began pushing for more economically progressive policies like universal health care, Social Security and child labor laws. But after the 1950s, issues like Civil Rights Movement, the Vietnam War and Roe versus Wade politically divided Catholic workers. Many began supporting anti-union politicians because they agreed with them on social issues and Cold War foreign policy.

“Between the early 1960s and 1980 there were these elements of a perfect storm,” said Seavey. “I think there have always been efforts to keep the pro-labor teachings alive within the church, but they just became far less influential than they were in the 1930s through the early 60s. Part of it was that we were so successful in getting so many masses of Catholics educated through the GI Bill and earning better wages that the Catholic enclaves broke up in the big cities. Those people began to move into the suburbs and other neighborhoods. There was sense that ‘well, we don’t need unions so much anymore.’”

Seavey was in seminary when Ronald Reagan defeated former President Jimmy Carter 1980 and remembers how divided the students were in their political allegiances. But during the following year, Pope John Paul II issued another encyclical titled "Laborem Exercens” (“On Human Work”), which called for greater power for workers in workplace management decisions and determining the fruits of their labor. It also addressed the crisis of unemployment and called for fairer treatment of migrant workers and people with disabilities. It urged the creation of a “family wage” to support families and the labor of rearing children.

At the time, Laborem Exercens was widely seen as supporting Solidarity — a massive Polish labor union representing one-third of the nation’s working-age population that fought for workers’ rights and helped put an end to Communist rule in Poland. Seavey said reading the encyclical was like the “scales falling” from his eyes as it introduced the idea that work is more than just an activity or a commodity, but an essential part of human nature that includes parenting, hobbies, rest and recreation, prayer life and more. The Pope wrote that when we work, we are “co-creators with God” and then through Baptism we are “co-redeemers with Christ.” For Seavey, this meant rethinking so much of what he learned in American culture about labor and the economy.

“I had always seen work as something that was secular, but I began to see that in the eyes of the church that all of creation is basically good, so that our encounter with creation is meant to be something that is good and develops over time,” said Seavey. “God might make a forest, but only people can make furniture or homes. God gives us the raw materials, but only people with the skills God gave them can make things from that. The primary foundation teaches that the work is for the worker, not the worker for the work. This means we need to center the worker in everything we do, like paying people living wages and family wages.”

These days, Seavey is working on building stronger links between the labor and faith communities to empower union members to advocate with their clergy for workers rights.

“With a deeper understanding of human dignity extending to the workplace and a greater realization of the dignity of work itself, faith communities deepen their experience of expressing belief in a divine presence along with a deeper experience of worship,” he explains. “This becomes a source of energizing renewal.”

Ultimately, Seavey’s goal is to form what Martin Luther King called “Beloved Communities” where all are welcome regardless of race, gender, sexual orientation, religious affiliation (or no affiliation), economic class, ethnicity, or political identity.

“I think unions are about building community. Faith communities are about building community,” he said. “I think if the two of them got back together that would be a really significant force in towns, neighborhoods and lives.”