The Founders of Maine’s First Firefighter Union Struggled with PTSD & Terminal Illnesses Due to Their Work

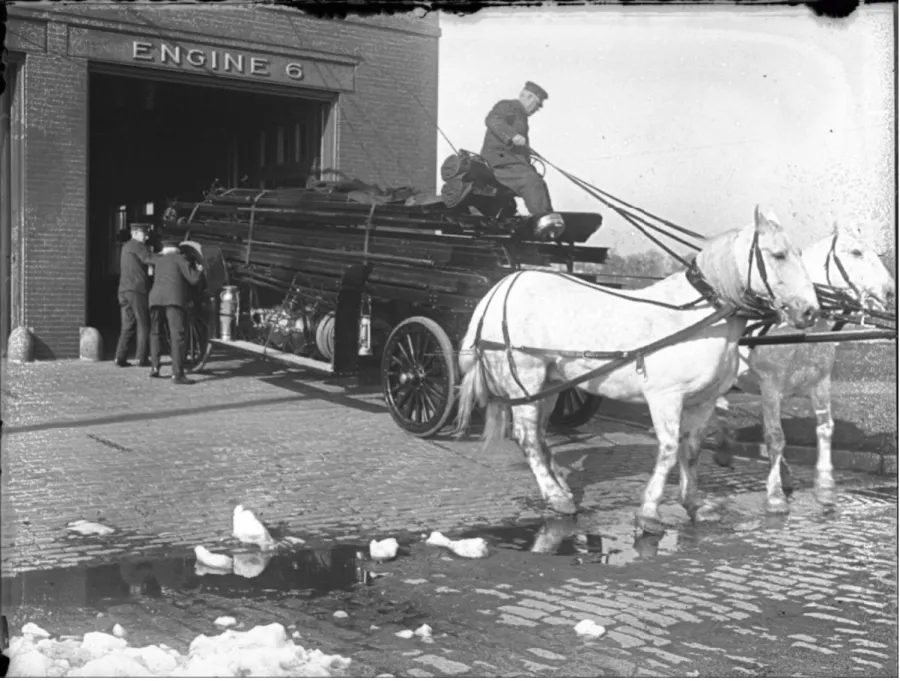

Ladder 6, Portland, 1924. Credit: Maine Historical Society

In our last installment on the history of firefighter unions in Maine we covered the devastating defeat of the Portland Firefighters (IAFF Local 133) in their effort to win two shifts in a municipal referendum. The union dissolved shortly after the loss. Sadly, most of the officers in Local 133 either died or left the fire service due to struggles with post-traumatic stress disorder before they were able to retire. Their stories serve as a clear example of why they needed the rights and protections that a union could have provided.

Local 133 President William J. Hawkins was promoted to Captain in July, 1921. He was nearly killed a year later responding to an iodine explosion at the wholesale drug and chemical company Brewer & Co. Inc. Hawkins and two other men were running a line of hose into the rear of the building when several bottles of acid exploded, enveloping them in heavy toxic fumes and knocking them back into the street. According to news reports, it was several minutes before the firefighters were able to get back to fighting the flames.

For over five hours, the firemen poured tons of water into the building before the fire was finally under control. Hundreds of people on their way to the islands lined the Portland Pier to view the blaze. Several firefighters were injured at the Brewer & Co. fire, including Local 133 Financial Secretary John Gubbins. The Portland Sunday Telegram compared the Brewer fire to the 1913 deadly chemical spill at the H.H. Hay & Sons pharmacy that killed Deputy Chief William H. Steele and Lieutenant Ralph Eldridge and nearly killed Gubbins. It's not clear what the extent of his injuries were at Brewer & Co., but the H.H. Hay incident kept him laid up for three months and it was another six months before he could return to work.

Two years later, Hawkins died at the age 48. It’s unclear how he died or if it had anything to do with his exposure to toxic gases in his work, but he had reportedly been ill for some time. Hawkins was known for having many friends and being a “fearless and efficient fire-fighter.” He left behind a wife and four daughters.

Gubbins, who was promoted to lieutenant in 1922, he made a dramatic rescue of an elderly, invalid woman at a lodging house on State Street the following year. According to news reports, he found the woman by groping through thick, black smoke, wrapped her up in a blanket and carried her down the stairs through a window to a second story piazza roof and in the safe arms of the other firemen. But the trauma of his work and his home life began to take a toll on his emotional well being. In 1920 his wife Abbie Conroy fell ill with pneumonia after taking care of the family stricken with influenza. She died that January, leaving him and their two daughters. Gubbins remarried, but he began to hit the bottle hard and started behaving erratically. His years of responding to some of the most serious fires in the city's history also began to take a toll on his mental health.

On March 6, 1926, Gubbins responded to a roaring blaze at the Dirigo Fish Company at the end of Union Wharf. As firemen responded, explosions of ammonia from refrigeration tanks shot flames farther across the wharf, spreading the flames dangerously close to the other buildings. Waldo H. Perry, a call man who had retired from being a full-time fire fighter, was sent to the hospital after he was clothes lined by a fire hose while running to the blaze. Gubbins was physically unharmed, but the Dirgo Fish fire was his psychological breaking point. He had been on duty at the blaze for about 30 hours with only a one-hour rest at noon and four or five hours late in the afternoon. Gubbins reported back to the fire at 9pm and remained on duty until 7:40am the next day.

By that time, his drinking had gotten totally out of control and his marriage to his second wife began to fall apart. Two weeks after the fire, he was arrested after coming into work drunk and using profane and abusive language toward the Fire Chief. It wasn’t the first time he had come to work drunk. After 15 years in the department, Gubbins’ career was in a tailspin. He was demoted from lieutenant to private.

He was later suspended after being arrested for beating up his wife and demolishing the inside side of his house with an axe while blackout drunk. He didn’t attend his trial that July because he was “in a highly nervous state and laboring under mental agitation,” according to his lawyer. Gubbins said he began drinking due to stress and exhaustion from the long shift fighting the Dirigio Fish fire and his marital troubles.

He also testified that he was still experiencing psychological trauma from exposure to toxic fumes at the 1913 chemical spill at H.H. Hay and Sons pharmacy. By 1932, Gubbins had been let go from the department and had been arrested about a dozen times. He went to jail again in 1935 for breaking a door. But it doesn’t appear that he got into trouble after that and his wife stayed with him. In 1940, he was 52 years old and working as a caretaker. Gubbins died in a nursing home on March 29, 1965.

Local 133 Recording Secretary William E. Fuller went on to become Captain of Portland’s Central Station in 1925 and co-founded the Maine Firemen’s Association in Lewiston in 1927. Fuller was elected as the first president of the statewide organization, which was formed “for the mutual benefit of all firemen" and "render financial aid to the widows and other dependents of firemen who are injured or killed in the service.” Little did he know that his family would someday have to take advantage of this benefit.

On July 9, 1929, Fuller responded to a three-alarm fire at a warehouse on Kennebec Street. The fire was reportedly the hottest blaze in the city in a decade and Captain Fuller was among several firefighters who were injured that day. It’s not clear what the injury was, but it might have been from inhaling toxic fumes. He attended one last Maine Firemen’s Association convention as a delegate on August 27.

On October 18, the Portland Evening Express reported that Fuller was critically ill in Maine General Hospital and had been unable to work since September. As Fuller’s family struggled to make ends meet without his income, he filed a petition to the city to allow him to continue to get paid because he said his injuries were the result of the fire in July. However, Portland City Manager James E. Barlow and the City Council argued that there was a “danger of establishing a precedent” if they made an exception from the ordinance and continued paying Fuller. Instead, they suggested that firefighters and police officers should be subjected to annual physical examinations to make sure they were healthy enough to serve. “This, of course," they noted, “would mean retirement of those failing to demonstrate physical health consistent with the job.”

Captain Fuller lingered for another two weeks and then died on Nov. 2, 1929. He was 47 years old and left behind his wife Mabel, two sons and two daughters.

The Portland firefighters continued to fight for dignity, fair wages, work place safety and a life outside the fire house for many years after. The struggle would eventually culminate in the reformation of the Portland Firefighters’ Union and showdown with the rabidly anti-union City Manager James E. Barlow over a revived two-platoon system in the 1940s. More on that in the coming weeks.