EMMC Nurses & The Five-Year Fight to Win Union Recognition

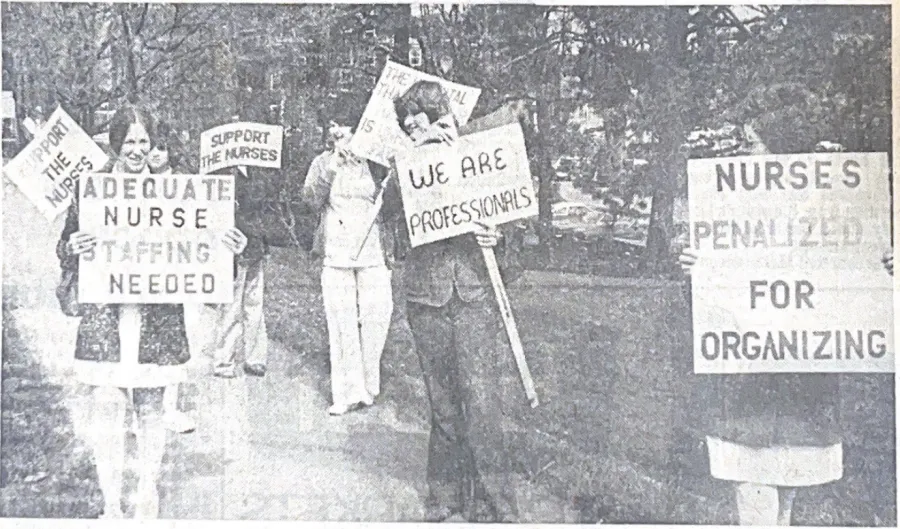

PHOTO: EMMC nurses picket outside the hospital in April, 1977.

This is part two in a series on the history of nurse organizing in Maine. You can read part one here.

When nurses at Eastern Maine Medical Center in Bangor won their union election by 14 votes on March 19, 1976, that was the “easy” part. They couldn’t imagine that it would take another five years of legal wrangling before the hospital was finally forced to bargain with them by court order. After being publicly embarrassed by the victory, EMMC’s Board of Trustees, its President Robert Brandow, and his hired anti-union consultants weren’t about to give the nurses an inch.

The Businessman's Board

The EMMC Trustees included representatives from some of the largest and most anti-union employers in the state. They included Chairman Doug Brown, President of the Doug’s Shop ‘N’ Save grocery chain; Ralph E. Leonard, Chairman of contractor H.E.. Sargent Inc., and Clifton G. Eames, President of N.H. Bragg, a Bangor industrial equipment supplier. Other members included the presidents of Bangor Savings Bank, Merrill Trust Bank and Merchants National Bank as well as the vice-president of the Dead River Oil company, a Republican legislator and lawyers with the firm Mitchell and Stearns and Eaton Peabody, the hospital’s employment attorney.

Perhaps most striking, given the negative coverage the nurse’s campaign received in the Bangor Daily News, was that EMMC’s board also included Arthur McKenzie, vice president, treasurer and general manager of Bangor Publishing, the parent company of the BDN. This was a fact briefly mentioned in the paper at the time, but not McKenzie’s connection to the newspaper.

Brown had served on the Bangor City Council as well as several community boards, from EMMC and the University of Maine Foundation to Husson College and the Governor’s Business Advisory Council. He liked to say that his business philosophy was “to take care of the customer first, the employees second, and the stockholders third.” But in practice, Brown was ruthless when it came to labor disputes at his stores, which Hannaford Brothers owned a majority stake in.

Five years earlier, workers at Doug’s Shop ’n’ Saves in Bangor, Brewer, Old Town, Ellsworth, and Bucksport organized a union after Brown forced six employees to submit to a polygraph test when some stock went missing. Brown’s refusal to agree to a union security clause provoked a long, bitter strike that was marked by court injunctions against picketers and an alleged plot to firebomb a Waterville supermarket. In the end, Brown defeated the workers and they returned to work eight months later without a contract. During the struggle for union recognition at EMMC, nurse Dottie Barron and several of her coworkers refused to shop at any Doug’s Shop ’n’ Save stores.

“There weren’t many of us who didn’t shop there anymore and I’m sure it didn’t make any difference, but politically I just couldn’t do it,” said Barron.

Brandow and the EMMC trustees followed a similar strategy of stonewalling in negotiations with the nurses, often postponing bargaining dates and even failing to show up for scheduling sessions. After more than a year, the two sides still had not reached an agreement. Meanwhile, the administration approved raises for other non-union employees, effectively providing fuel for the anti-union nurses who had collected enough signatures to hold another vote on the union. Some of the clinic nurses issued a statement to the press announcing their disapproval of the collective bargaining effort.

Pro-union nurses struggled to get their side heard because company rules prohibited them from talking to other nurses about the union, even when they were off duty and in non-working areas. The Bangor Daily News seldom ran pro-union letters to the editor. Eventually Barron and a group of nurses got together and made an appointment to complain to the newspaper’s editorial board.

“We’re sitting up in a balcony-like office and they’re saying ‘oh no no, we only print so many of everything that comes in' and we’re like ‘well how come none of the nurses’ letters are being printed?” recalled Barron. “Suddenly, the hospital’s lawyer comes bursting in downstairs screaming, ‘‘Who the hell wrote this article?!” not knowing there were about eight of us nurses sitting upstairs with the administrator on the balcony. We had one reporter who, when she could, would write what I called a ‘fair article’ [about the EMMC nurse campaign].”

Barron said the reporter later told the nurses that she “had to be careful” or she would get fired for what she wrote.

“Oh yeah, they owned the Bangor Daily back then…. But we did get a few nurses’ articles in the next two weeks,” she added.

A De-cert and a Re-cert

PHOTO: EMMC RN Christine Harrington demonstrates at a picket. Photo by Jack Loftus

After a mediator declared an impasse in bargaining in February, 1977, pro-union nurses organized their first informational picket to call for a fair contract. In response, Brandow had letters delivered to the hospital’s 300 patients bad mouthing the nurses as “unprofessional” and unethical. The hospital expressed “grave concern over the psychological impact the picket could have on the patients.”

“Say you’ve got a woman from Millinocket with a child year,” hospital spokesman James Coffey told reporters. “She has to work. While this [picketing] is going on, she’ll be asking herself, what is going to happen to my loved one down there in Bangor at EMMC?”

The administration also sent telegrams to MSNA leaders falsely declaring the informational picket “illegal” and threatened to file a complaint to the NLRB if they did not cease immediately. Speaking to reporters, the MSNA local President Pat Martin dismissed the letter as “another tactic to try and scare us.” When asked by the Bangor Daily News to comment on the hospital’s claims that the picketing was psychologically harming patients, Martin vehemently disagreed.

“Most of the patients were not even aware of it until the hospital dragged it up for them,” she said. “It’s nonsense."

The hospital even sent out staff to photograph nurses on the picket line, which many of them saw as an act of intimidation. Retired nurse Dottie Barron recalled standing on the picket line when a man drove up in his car.

“He points up to his administrative office in the older part of the hospital and says, ‘They’re all the same. They’re on boards of the banks. They’re on the boards of both hospitals. They’re on the university [board]. Those people don’t care.’ He got back into his car and he drove off. It was true.”

At the end of July, 1977, the EMMC nurses voted 132-81 to decertify the union and leave the Maine State Nurses Association.

Union President Pat Martin attributed the results to the collective bargaining process taking too long because of the lack of across the board raises and “because the hospital hired two consultants and two lawyers, and conducted a daily campaign to discredit nurse organizing.” Martin noted that the administration had the backing of the powerful Maine Hospital Association, and that EMCC had paid the cost of flying four nurses back from vacation in order to vote.

But the fight wasn’t over. The nurses filed several unfair labor practices against the hospital charging that it failed to bargain in good faith, withheld wage increases to discourage union activity, unfairly prohibited off-duty nurses from advocating on behalf of the union in non-working areas of the facility, and interrogated prospective nurses on their views of the union.

A year later in October, 1978, Judge Robert A. Giannasi, an administrative law judge at the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB), invalidated the decertification election because hospital officials committed unfair labor practices by not bargaining in good faith. The court also found that the hospital illegally prohibited pro-union nurses from soliciting their coworkers to join the union during off-duty hours and in non-working areas and unlawfully withheld wage increases from nurses who supported the union while granting increases to anti-union nurses. The judge called on the hospital to reimburse MSNA for collective bargaining costs incurred during negotiations.

Meanwhile, negotiations were still stalled because EMMC appealed the decision. Barron recalled the stress of being deposed and having to testify at court hearings and the NLRB.

“The whole process dragged on and on and anything they could bring up to stall it happened,” said Barron. “We were all a wreck because we knew we had to testify.”

It wasn’t until August, 1981 that a First Circuit Court judge in Boston rejected the appeal and ordered the hospital to bargain in good faith with the Maine State Nurses Association’s 235 members. MSNA spokesman Patrick Scanlon called EMMC’s appeal “a delaying tactic to postpone collective bargaining in good faith” and an unsuccessful effort to bankrupt the union. While the hospital seemed to have endless resources, the nurses struggled due to having to take time away from work for negotiations and hearings. At one point the nurses had to turn to legal aid because they ran out of money.

“We are absolutely delighted at the court’s finding, and we look forward to sitting down and negotiating in the near future,” Scanlon told the Bangor Daily News.

A month later, the nurses finally received $190,000 in back wages with an average reimbursement of $450 plus $125 interest for withholding raises from union members.

Next week: The first union nurse contract in Maine.