Black History: How Portland's Red Caps Organized for Better Lives

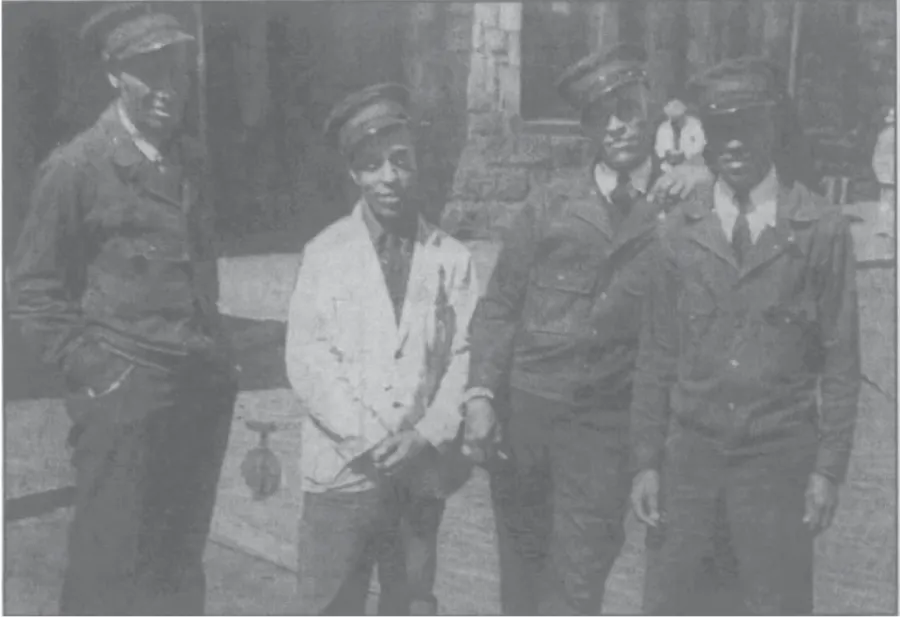

Photo: From left, Parker Watts, Charley Cook, Leslie “Tate” Cummings and Bill Graham worked at Portland’s Union Station until it was torn down in 1961.

In the late 1930s, African American luggage handlers at Maine’s major rail stations in Portland, Waterville and Bangor decided it was time to get organized to fight for a fair wage and humane working conditions. They were known as “Red Caps” for the hats they wore that made them clearly visible for weary travelers in need of assistance. Roughly a dozen Red Caps carried bags, cleaned bathrooms, cooked and served food to passengers traveling in and out of Portland’s Union Station on St. John Street before it was torn down on August 31, 1961.

In the 1930s and 40s, Red Cap brothers Charles “Eddie” Cummings, Leslie “Tate” Cummings and Eugene “Gene” Cummings all worked for the Maine Central Railroad at Union Station. In those days, career opportunities for Black workers were very limited due to racial discrimination. Working as a Red Cap was one of the few opportunities they had for steady employment.

As Gene’s son Leonard Cummings told the Portland Press Herald in 2002, one of his relatives, who was a pharmacist, once came to look for work in Portland. When he couldn’t find any place that would hire him he took a job as a Red Cap. Eddie Cummings was bright and ambitious, but he and his wife Rose Shurtleff Emerson Cumming also had seven children to support.

“Although he could have been whatever he wanted, he made the best of it with what was available for him,” Leonard Cummings said.

Being a Red Cap was also considered a prestigious job in the Black community and they were well-respected. They were highly disciplined and trained to be polite and courteous at all times.

“It was somewhat left to black people that (service railroad jobs) were their position,” veteran civil rights leader Gerald Talbot told the Press Herald, “but for black people to hold that position and to be respectable and cordial and kind. To be personable and to be the best they could be, they brought dignity to it.”

Eddie Cummings was very proud that he came to know personally many famous people while carrying bags for like First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, Senator Edmund Muskie, opera singer Marian Anderson, composer Roland Hayes, author Kenneth Roberts, novelist Booth Tarkington and many more. When they came to Portland, they requesting Cummings by name.

Red Caps Organize Their Union

However, Red Caps’ earnings wildly fluctuated because they relied solely on tips before 1938. Eddie Cummings relied on working a number of jobs, including running a cleaning business, in addition to his full-time work at Union Station. In 1923, Eddie Cummings and his wife opened a guest house that catered to Black tourists, including many traveling musicians, out of their home at 110 Portland Street. At the time,Maine inns and hotels were allowed to refuse lodging to Black guests and it wasn't until 1971 that Maine passed a law making it illegal to discriminate Black people in accommodations. Tate Cummings ran a side business selling coffee, muffins and doughnuts to workers at the station.

As the Bangor Daily News noted reported their tips were “slim” due to the Depression and the Red Caps in Bangor’s Union Station hoped that the job would get their feet in the door to find better paying jobs as porters on the trains. As Red Caps struggled to keep their households afloat on tips alone during the Great Depression, they began organizing for union protections, shorter hours and a minimum wage.

In 1937, Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters members at the Pullman company inspired Black workers across the country by becoming the first Black-led union to win a collective bargaining agreement with the the single largest wage increase they had ever received, a 240-hour work month, proper rest times and guaranteed pay for preparatory and terminal time.

Taking a cue from the Pullman porters, Chicago Red Cap Willard Saxby Townsend led a national campaign to organize Red Caps that same year with the CIO. In the beginning, the burgeoning union suffered internal racial divisions and after white union official was charged with misappropriated union funds, the white members left the union to join the Brotherhood of Railway Clerks, a rival AFL union that was only open to white workers. But that didn’t stop the Red Caps union's momentum.

At first, Townsend printed thousands of pro-union leaflets that he handed to Pullman Porters to distribute to baggage handlers in rail terminals throughout the nation. Then he and two other organizers bought an old car and headed east to meet with Red Caps throughout the East Coast. With a shoe string budget, they relied on contributions from Red Caps at their meetings, but they eventually had to abandon their car for lack of money. They finished the rest of their organizing journey by hitch hiking.

At some point along the way, they likely met with baggage handlers in Maine.

The Battle Over the Tipped Wage

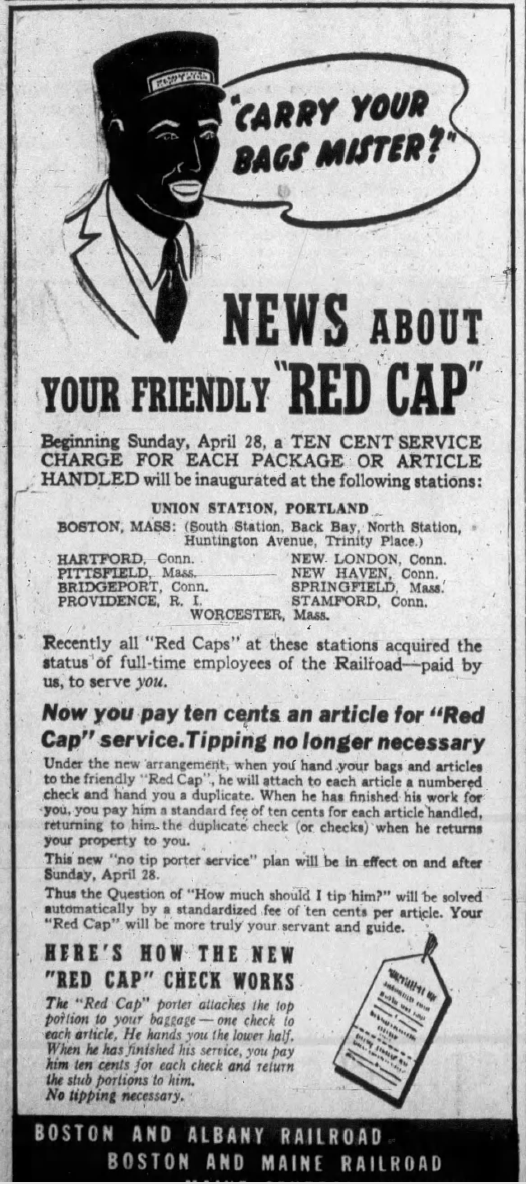

But even though Red Caps were increasingly unified, they didn’t have any power at first because the rail companies classified them as "privileged trespassers” on rail road property rather than employees. But after successfully petitioning for employee status with the Interstate Commerce Commission, the International Brotherhood of Redcaps gained union recognition and the baggage handlers were made eligible for a minimum wage under the Fair Labor Standards Act. It was later affirmed in a 1840 Supreme Court decision. Finally, they had won their hard-fought battle for a steady, reliable wage in addition to tips. The union changed its name to the United Transport Service Employees (UTSE) that year after it became recruiting Pullman laundry workers.

Rail companies responded to the court decision by charging a ten-cent per-bag fee to pay the handlers the minimum $2.40 minimum wage per day. It was very controversial at first. The Bangor Daily News in particular several critical stories about the policy, claiming in January, 1839 that the “boys” who handled baggage at the rail station had “allegedly” been let go due to the new wage system. But in later years it was reported that Red Caps still worked at the station.

In an April, 1940 story titled "Red Caps Fear They’ll Wind Up in Red As Tips Vs. Pay Row Nears Decision,” the BDN ran a headline raising the question if the Supreme Court would decide whether the Red Cap is “rugged individualist competing for your business at any rate his smiling service can command? Or is he a wage-worker?” The paper claimed that Red Caps were alarmed that the “$2.40 minimum per day tends to become a a maximum” because customers would tip less.

Indeed, there were many Red Caps in other states who expressed concern that travelers were tipping less and this put union leaders at odds with some rank and file members. In a 1941 story titled “Boston’s Bluebloods Protest 10c A Parcel Carrying Fee,” a Portland Red Cap named Oswald Jordan told the AP that passengers felt “exploited” by having to pay the 10-cent fee.

However, when a Portland Evening Express reporter asked Eddie Cummings how he felt about the new fee system in April, 1940, he was optimistic.

“We have nothing against this new service,” he said, acting as spokesmen for the Portland Red Caps. “We are here to work and to cooperate with the railroad officials. We will try it out and see how to works.”

Cummings said that the Red Caps didn’t expect to get any more tips, but they would continue to earn decent tips from their longtime summer visitors. He figured travelers would be opting to carry their lighter items like sweaters and jackets rather than pay the fee for each one, but overall the system would be beneficial to the luggage handlers.

“Our big business,” he explained, “comes during the three summer months. Getting a regular salary during the other nine slack months might even matters up all around and prove a benefit rather than a detriment.”

He added that tipping had steeply declined in recent years anyway, likely due to the Depression.

“The dollar today is only worth 49 cents,” he said, “and we porters taking our licking accordingly. The fellow who used to tip a dollar now tips 35 cents and the fellow who used to tip half a dollar now gives us 15 or 20 cents. People riding on the railroad have just so much to spend. If they have been in the habit of tipping 20 cents and find themselves with four bags, they’ll carry two and give us two and that will take care of the 20 cents.”

Despite all of the fear mongering about loss in tips and jobs, even the Bangor Daily News begrudgingly acknowledged that Red Caps in Maine were doing much better after unionizing. In addition to higher wages, Rep Caps union members quickly achieved shorter working hours and seniority rights.

“Today, a 'Red Cap,’ who works 8 hours a day on a 7-day week gets a salary of $50.96 per week from the Boston and Maine or the Portland Terminal company and one who works 6 days a week gets $43.68 — plus, of course, tips,” it wrote in 1947.

Some news articles from that time revealed an underlying racism in opposition to granting the Red Caps a minimum wage. Tipping became widespread in America after the Civil War as employers exploited newly emancipated African Americans by forcing them to solely rely on tips in service positions like waiters and porters. Racist employers and others believed it was improper to provide Black workers with the same wages and worker protections as white workers. Labor leaders and progressive reformers at the turn of the century fought an unsuccessful battle against tipping because they saw it as a form of worker exploitation.

In a 1946 column in the Portland Evening Express, conservative commentator George Ephraim Sokolsky took aim at political leaders and the labor movement for empowering and emboldening Black workers.

"The citizens are used to being pushed around as they are getting accustomed to standing in line for their daily necessities or to get a meal in a restaurant, to being sassed back impudently by a clerk or a Red Cap or a waiter.”

Unfortunately, passenger rail service began to decline in the 1950s as more and more people turned to automobiles and air travel. Portland’s Red Caps later took jobs as “skycaps” at the airport in South Portland and by 1969 membership in the United Transport Service Employees plummeted to 3,000 members, less than half of what it was in the late 1950s. In 1972, it merged into the Brotherhood of Railway Clerks. While Red Caps are still employed in major railroad hubs, there are none in Maine anymore. But their legacy of fighting for civil rights and workers rights is still with us today.

Eddie Cummings worked for 50 years as a Red Cap and put six of his seven children through college with the money he earned.