AFL-CIO Secretary-Treasurer Redmond & WSLC Pres. April Sims Emphasize Civil Rights & Labor Connections and the Transformative Power of the Labor Movement at APRI Dinner in Portland

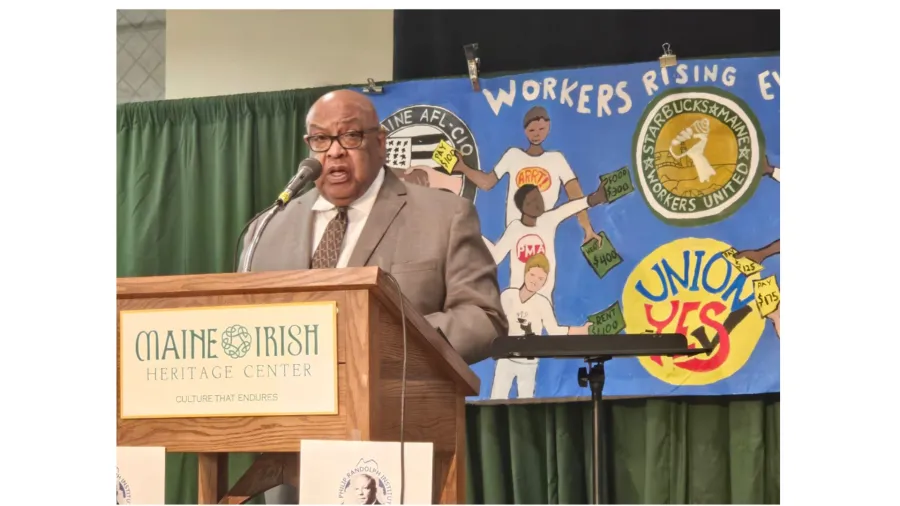

PHOTO: Secretary-Treasurer Fred Redmond speaking at the APRI-Maine dinner on March 9.

About one hundred union members and allies attended the A. Philip Randolph Institute dinner last Saturday at the Irish Heritage Center in Portland as part of our ongoing work to build a multi-racial labor movement that fights for racial and economic justice. At the event, AFL-CIO Secretary-Treasurer Fred Redmond and Washington State Labor Council President April Sims delivered powerful remarks about the transformational power of unions and our vision for a more fair, equitable and just society.

In his remarks, Brother Redmond referenced Dr. Martin Luther King’s famous speech before the 1961 AFL-CIO Convention in which he pointed out that the needs of the Black community were “identical with labor’s needs — decent wages, fair working conditions, livable housing, old age security, health and welfare measures, conditions in which families can grow, have education for their children and respect in the community.” As King told the convention, “The duality of interests of labor and Negroes makes any crisis which lacerates you, a crisis from which we bleed.”

Redmond said the AFL-CIO is working on continuing this legacy by building relationships with the civil rights movement and centering racial justice in all of the work we do.

“We’re making an intentional effort to recommit ourselves to join together with our friends and our allies in the civil rights and social justice movements, not only because we are stronger together, but because our mission of justice that expands opportunities for all people, especially those of underserved communities, are uniquely connected,” said Redmond. “And the A. Philip Randolph Institute will be a key partner in this work."

Redmond served as chairman and as a board member for the national A. Philip Randolph Institute, a constituency group of the AFL-CIO that focuses on racial and economic justice, for fifteen years. He told attendees Saturday that he has never seen the labor movement so committed to racial justice as this moment in history. As the son of a union worker, Redmond said he has seen first-hand how unions can be transformative for families.

From Sharecropping to Economic Stability with a Good Union Job

Redmond’s family is originally from Mississippi where they were sharecroppers — an exploitive post-slavery arrangement that required his father to work on another man’s land as a tenant in return for a share of the crops produced. In 1953, Redmond’s family moved to Chicago because his father wanted his four boys to have a better life. There his father pumped gas and stocked supermarket shelves while hauling junk in between jobs while his mother worked as domestic worker cleaning other families’ homes and cooking them meals.

“We grew up with a happy childhood. We played and did things that kids do and did not know the economic situation around us,” said Redmond. “They used to collect money at school on Friday for the local orphanage and I remember one of my brothers going to my mother and said, ‘I need a quarter for the poor kids.’ And it was at that moment when my mother had to sit us down and explain to us, ‘Ya’ll are the poor kids. Understand this.’”

In the beginning, Redmond’s family had to apply for food stamps to supplement their income and his mother bought the children’s school clothes at Goodwill. Then suddenly things changed.

“No longer did we go to free clinic. We started going to a doctor’s office,” said Redmond. “Mama started going to the Goodwill to drop off clothes instead of buying clothes and started shopping at Sears. It was a big deal. My father was able to save and buy a brand new used car. We went through a change, but I was too young to realize what was happening.”

It wasn’t until later that Redmond learned his father had gotten his first union job. With his union negotiated wages, the family was able to purchase a home and save for retirement.

“When you think back and you compare that time with the time when we’re in now, it was those sort of jobs that supported and lifted up communities all across this country,” he added. “Working on a collective bargaining agreement and a good union job was always the first step in reversing an unequal system that has caused generations of damage throughout this country.”

Earlier in the day, Redmond met with new LIUNA 327 apprentices, several of whom just graduated from the Union Construction of Academy of Maine. During the speech he praised the Maine Building and Construction Trades Council for growing opportunities for people of color and other communities that have historically been left out of union trades. He noted that the number of registered apprentices in Maine nearly doubled last year.

“A. Philip Randolph once said that a solid contract is in a very real sense, another Emancipation Proclamation,” said Redmond. “We know that a collective bargaining agreement is the single most powerful tool to make sure that all workers are included, that our workplaces are diverse and accessible, that there is equity in hiring practices, pay and advancement opportunities and that workers gain the skills needed for jobs of today and the jobs of tomorrow.”

"Baby, if I can just keep this job it’s going to change our lives”

WSLC President April Sims also described her family’s own struggles in the deep South and how unions transformed their lives. Her grandparents were sharecroppers in Louisiana and picked cotton to survive. One day, her grandfather Theodore Turner realized the landowner was shorting some of the Black families and paying white farmers more with the crop payout. In response, he organized other Black families to protest the discrimination.

“I like to think of him as a union organizer. But as you can imagine, that created some problems for the family,” said Sims. “The landowner sent some men to the house and they dragged my grandfather out to the whipping post. They were intent on making an example out of him. And my grandfather was a strong, proud man and he fought back and escaped, but only because he used what he always referred to as his Texas jag, which was this knife he kept tucked inside his right boot.”

While Turner was able to escape, he knew that he would be lynched if the white men caught him, so he fled to Northern Louisiana where her great grandmother told him, "You can stay, but you’ve got to learn how to keep your head down and your mouth shut because we don’t want those kinds of problems around here." It was the 1940s when Sims’ grandparents joined the Great Migration, one of the largest movements of people in US history, when roughly six million African Americans moved from the South to the North to escape racial violence and Jim Crow discrimination and to pursue more economic and educational opportunities.

“He knew he couldn’t raise his family with any dignity in the segregated South and my grandfather dreamt of a better life, not just for him but for his children and his children’s children,” said Sims. “So he left my grandmother and the family in the safety of her family and he migrated to Washington in search of economic and racial justice. And here, for the first time, he earned a fair day’s pay for a hard day’s work.”

While working at the Hanford Nuclear Plant in Eastern Washington, Turner was able to earn enough money to support his family, but they lived in an original “sundown town,” a traditionally all-white community that banned Black families from living there. African-Americans were often threatened with violence if they were caught there when the sun went down.

“It wasn’t until the family moved to Seattle that my grandfather got a job as a janitor at a department store and was represented by Teamsters 174 that he had both the economic justice and racial justice he was seeking when he fled the South,” said Sims. “So for me and my family and my community, the struggle for economic justice and the struggle for racial justice were inextricably linked. They are the exact same struggle. One cannot simply exist without the other.”

Sims was raised in the 1980s by a single mother, Sherrie Courtier, who worked very hard, but she was unable to get ahead. For a time, the family was homeless and had to rely on public assistance.

“I remember her frustration and desperation,” said Sims. “For every three steps she would take forward, something would push her back. We were trapped in this cycle of poverty. Then she got a union job and things changed. I remember her coming home from her interview and she said, ‘Baby, if I can just keep this job it’s going to change our lives.’”

Sherrie’s union negotiated contract did change their lives by ensuring that her hard work was rewarded with a a livable wage so she could pay the light bill. Her union contract included benefits like paid sick leave and health care so she didn’t worry about whether she was going to make the rent when Sims and her two siblings all got the chicken pox back to back. When her employer reclassified her position, her union fought for her back pay. She was able to use that money to buy her first car, so she didn’t have to commute an hour and half on the bus.

“When her supervisor was making inappropriate comments she didn’t want to say anything. She didn’t want to risk her job. She knew her kids were counting on her,” said Sims. “She did mention it to a coworker who happened to be a union shop steward and her union shop steward told her, ‘You’re not the one who needs to worry about losing your job.’”

After 30 years of hard work and commitment, Sims said her mom retired with economic dignity and financial stability because of her union pension.

“And when I tell ya’ll Sherrie is living her best life right now, she is living her best life now,” said Sims. "She is traveling. Life is good.”

In 2018, union members elected Sims as Secretary-Treasurer of the Washington State Labor Council. Then in 2022, she became the first Black woman elected as President and Cherika Carter, another African American woman, was elected as Secretary-Treasurer. Sims said her understanding of the generational impact that a good union job can have on the life of families and communities is what drives her vision “for a labor movement that transcends race and place, gender and ability, ideology and sexuality — a movement where every worker sees themselves represented in our ranks and in our leadership.”

“That vision is made possible because of all of you, because of the work that you all are doing here in Maine," she said. “That’s because you all know that we are united by one simple and fundamental belief: that an injury to one is an injury to all. That my fight is your fight, that your fight is my fight and united, there is nothing that we cannot do. There’s no fight we cannot win. There is no challenge we cannot overcome. There is no obstacle we cannot move. Our solidarity is our strength.”

Join APRI-Maine Chapter to Fight for Racial & Economic Justice

Would you like to join the A. Philip Randolph Institute - Maine Chapter in the fight for racial and economic justice? APRI is now officially accepting memberships!

| Join APRI-Maine! |