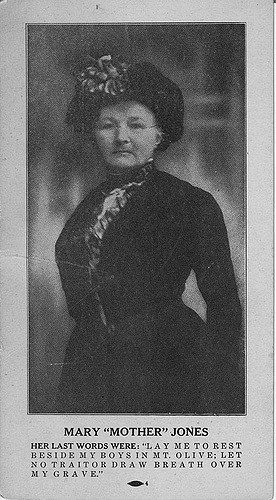

Actor & Playwright Kaiulani Lee Gives Riveting Performance as Mother Jones

In the past several weeks, award-winning actor and playwright Kaiulani Lee has been screening her riveting new film “Fight Like Hell: The Testimony of Mother Jones" around Maine. In "Fight Like Hell," written by Lee and directed by Maine filmmaker Ian Cheney, Lee delivers a powerful and captivating performance as the fiery and fearless labor organizer “Mother” Mary G. Harris Jones.

Lee brings Mother Jones to life, portraying her fierce passion for workers' rights and the deep empathy she had for the men, women and children laborers she spent her life organizing. Lee, who has a home in Phippsburg, says her goal is to make the film available to unions, schools and community spaces for workers to learn about the legendary labor leader who inspired millions of working people.

“Mother Jones had this powerful charisma and she stood behind this cover of being a nice old grannie,” said Lee. “She was considered dangerous because she had such power and authority. She was loved by workers, particularly miners, but also street car workers in San Francisco, bottlers in Chicago and garment workers in New York.”

Lee has spent her working career elsewhere, but she has deep roots in Maine and spent summers here as a child. Her mother’s family are Sewalls, a prominent Maine family who originally settled in Bath in the 1740s. As a kid, she was extremely shy and her parents joked that the reason why she wanted to become a forest ranger was because she wanted to hide in the trees.

While in college, she changed her career trajectory after meeting Czech-born actress Marketa Kimbrell after she lectured to her drama class. Kimbrell invited Lee to join the New York Street Theater, a socialist theater collective that performed to underprivileged and geographically isolated communities around the country and the world.

The following summer 20-year old Lee joined the New York Street Theatre Caravan, performing skits and plays about workers' rights, racial inequality, poverty and other sociopolitical issues on the back of International Harvester flatbed truck. The troupe performed for workers at union halls, sharecroppers in the South and migrant farm laborers with the United Farmworkers in California. They held performances in inner cities, Native American reservations, prisons, refugee camps in Nicaragua and the 1972 Munich Olympics.

Lee experienced some harrowing adventures during the theatre company’s tours. The troupe was performing for striking miners in Appalachia, when a pickup drove by and someone shot at the actors, blowing out the lights on their truck. During the tour of Kentucky and West Virginia, she was able to befriend miners and their families and was invited into their homes.

“In every cabin that I can remember, on one side of the door was a picture of Jesus and on the other side of the door was a picture of this old white woman dressed in Victorian granny clothes,” Lee recalled. I recognized Christ on the cross, but I had no idea who this woman was. After about three cabins I said ‘who is that?’ And they said, ‘you don’t know? It’s Mother Jones.’”

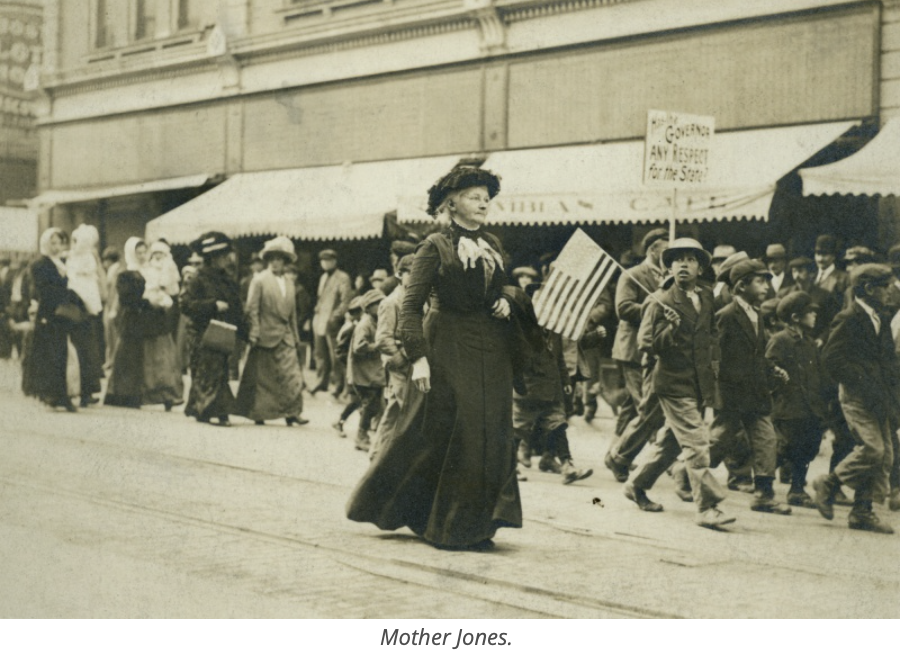

After Lee finished the tour she immediately started reading about Mother Jones to understand why she was so beloved 40 years after her death. A short, diminutive woman, her powerful presence belied her appearance. Unlike many union organizers of her time, she welcomed African American workers and even organized the workers’ wives, arming them with mops and brooms to guard mines against scabs. She staged parades with children carrying signs that read, "We Want to Go to School and Not to the Mines.”

Turning Pain into Power

Mary G. Harris Jones was born in Cork, Ireland around 1837 as a colonized subject of the British Crown. At the age of 10, she and her family were forced to flee their homeland due to what became known as the “Great Hunger.” Irish tenant farmers, who worked for absentee landlords, were reliant on the potato for sustenance so when a blight wiped out the potato crop in the 1840s, they began to starve.

Food grown in Ireland continued to be shipped out of the country while peasant farmers starved. Because politicians in England saw the Irish as inferior human beings and refused to deviate from free market orthodoxy to provide them relief, roughly a million people starved and another million people fled the country.

In researching for her play, Lee visited Cork, Ireland and spent time in the villages where the parents of Mary Harris grew up. She saw the giant cauldrons where villagers would throw potatoes and whatever plants they could find to make a thin broth to get some kind of nourishment while they slowly starved to death.

Young Mary Harris later trained as a dressmaker in Canada and eventually moved to Memphis, Tennessee where she married staunch union iron molder, George Jones, and had four children. Then in 1867, an outbreak of yellow fever swept through the city, taking her husband and all four children. After starting her life over in Chicago and opening a dress shop, she lost everything again in the Great Chicago Fire of 1871.

Lee compares Jones' attitude at that time to the way laid off autoworkers she met in Michigan felt after losing everything.

"They weren’t angry. They felt like they didn’t deserve the American Dream. Maybe they had aimed too high. They were just beat up,” she said. “Mother Jones was that way. She felt as a Catholic that she must have done something wrong and that was her lot. There was a deep hole in her heart.”

After the Great Fire, when she and thousands of other people became homeless, she began to realize that she wasn’t alone. She slept in a church pew in a church and found solace by attending Knights of Labor meetings.

“For the first time, she realized that this wasn’t her — that there were masses of women and children in her same position and she began to understand that that there was something unfair,” said Lee.

Jones focused her attention on the plight of the poor and working classes, child laborers and the families who had no safety net, unemployment, health care or pensions. She developed her oratory skills in Pittsburgh during the Great Railway Strike of 1877 and went on to lead hundreds of strikes, including the General Strike on May 1, 1886 in Chicago for the eight-hour day that culminated with the state execution of the Haymarket martyrs.

She found her family in working people all over the country and all over the world. She organized workers in Illinois of all ethnicities, races and backgrounds famously shouting, “Stop bickering with another. Join forces, join hands. Fight this battle together!”

“Her organizing filled a void in her and she wrote, ‘I will never let another woman go through what I have been through,’” said Lee. “I think her fierceness came out of this enormous loss, as she once said, “while I couldn’t save my own husband and children, I will fight to save yours.”

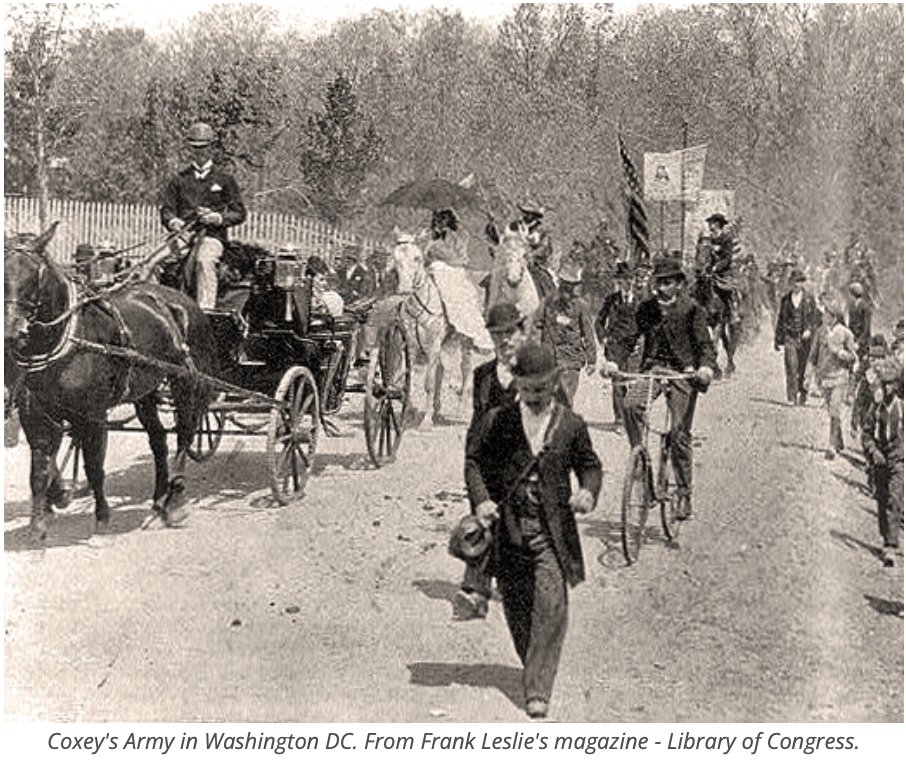

Jones volunteered to assist thousands of unemployed workers thrown out of work by the 1893 financial crisis, dubbed Coxey’s Army, in their march from Kansas City to Washington D.C. to demand a national jobs program. She backed Black and white miners in Birmingham, Alabama and supported a nationwide coal strike.

In the film, Lee's Mother Jones recounts the 1903 “March of the Mill Children” from Philadelphia to President Teddy Roosevelt’s Long Island summer home to draw attention to harsh child labor conditions to demand a 55-hour work week.

“I asked the newspaper men why they didn’t publish the facts about child labor in Pennsylvania,” said Jones. “They said they couldn’t because the mill owners had stock in the papers. ‘Well, I’ve got stock in these little children,’ said I, ‘and I’ll arrange a little publicity.’”

The President refused to meet with the marchers.

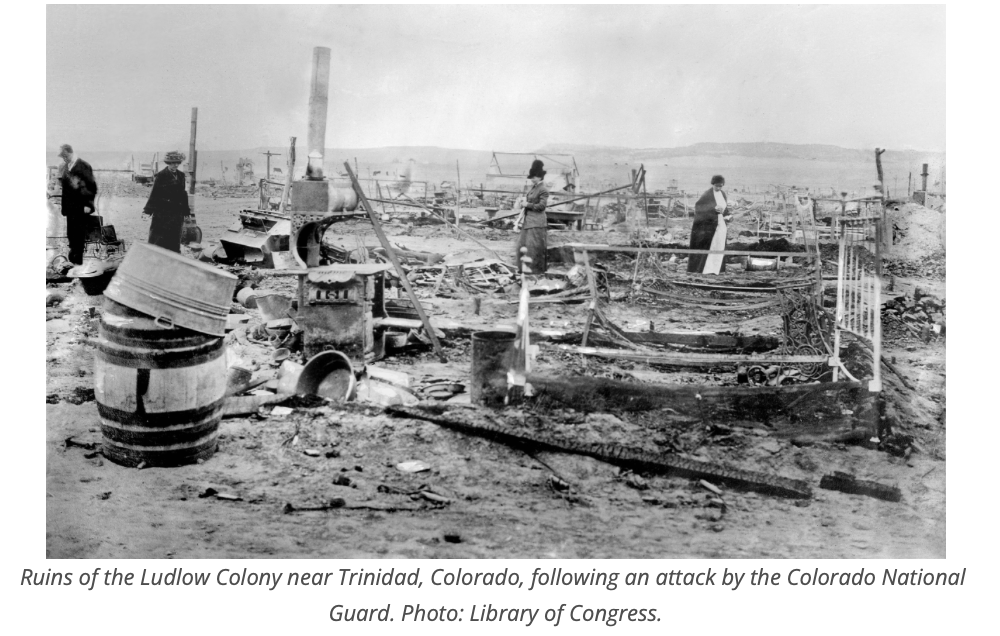

Jones had been supporting strikers in Ludlow, Colorado when on April 20, 1914, soldiers from the Colorado National Guard and private guards employed by the Colorado Fuel and Iron Company attacked a tent colony of 1,200 striking coal miners and their families, murdering 21 people, including miners' wives and children.

For her efforts, Jones was thrown into solitary confinement in jail, charged with a capital offense by a military tribunal in West Virginia in 1912 and put under house arrest until a mass mobilization of public support forced the Governor to release her. One Virginia judge called her "The Most Dangerous Woman in America” because, “At the crook of her little finger, she could get 8,000 men to walk out on strike.”

When Jones died in Silver Spring, Maryland, she was put on a train that took the exact route as Abraham Lincoln’s body to a massive funeral in Illinois. She was buried in the Union Miner’s Cemetery at Mount Olive, which she founded many years earlier. She was laid to rest next to the Virden "martyrs" — striking miners who were murdered by Chicago coal company barons during the 1898 Battle of Virden.

While researching for her play, Lee traveled to West Virginia and stayed in the state for a month gathering information. It was shortly after the 2011 Upper Big Branch Mine disaster that killed twenty-nine out of thirty-one miners 1,000 feet underground. She met the wives and mothers of the men who died and they told her about family members who developed cancer and black lung as a result of mining activity.

“They were like the daughters of Mother Jones. They had had it. They were angry,” said Lee. “I was so struck by their courage in speaking out.”

At one point while visited the site of the Upper Big Branch Mine, Lee was confronted by hostile company men with guns and was tailed for a long distance by company trucks. One day at the hotel she found that all of the air was let out of her car's tires.

“When I met with the United Mineworkers, one of them threw down a manila envelope and slid it all the way down on the long conference table. I opened it and there was a picture of my license plate, a picture of my car at the motel and a picture of me backing out after looking at a sludge heap,” said Lee. “They had been following me and thinking that maybe I was the press writing a bad story about Upper Big Branch.”

If Mother Jones were alive today, she probably wouldn’t be surprised to see that workers are still fighting for some of the basic rights that miners were fighting for over a hundred years ago.

“Then she would follow up immediately by pointing out, ‘Look at what we won. We can do it.’ Like she says at the end of the film, ‘Freedoms don’t drop from the sky while you sleep. Buckle on your armor. It’s a fighting age.’”