Boilermaker Jimmy McHugh Recalls “Fight Back” Campaigns of ‘88

In the late 1970s, nonunion contractors and repair companies began taking the construction industry by storm in a coordinated effort to drive down wages and fatten corporate wallets. These nonunion companies later took advantage of the anti-labor political environment of the 1980s to cut into the market share of unionized contractors and lower the bar for traditionally high skilled and well-compensated trades.

Members of the International Brotherhood of Boilermakers, Iron Ship Builders, Blacksmiths, Forgers and Helpers knew that if they didn’t get creative and find a way to reverse this trend, everything they fought for would be lost. That’s when union leaders came up with an organizing strategy they called Fight Back to regain those lost jobs and rebuild power in their unions.

The campaign strategy involved sending voluntary union organizers to apply for jobs with nonunion construction firms and writing UNION MEMBER on the top of their applications. If the contractors refused to hire or even consider the applicants on the basis of their union affiliation, the union would file an unfair labor practice with the National Labor Relations Board on the basis that it is illegal for companies to discriminate against workers who engage in protected union activity, such as organizing or promoting unions to other workers. Although there are no fines for this behavior, if the NLRB finds the company violated the law, it has to pay the workers what they would have made on the job. That money added up and caused those contractors endless headaches.

Boilermakers Local 29 member Jimmy McHugh was one of the Maine members who joined the fight in the 1980s. In those days, Brother McHugh traveled all over the state to jobs at all of the paper mills, power plants and other large industrial facilities. At that time, nonunion contracting companies like Cianbro were gobbling up a lot of what was once union work.

“It was hard to compete with those companies because our package was $50-$60 an hour and theirs was about $35 or $40,” recalled McHugh. “But they treated their workers like garbage and lots of times they couldn’t even get qualified help, especially welders.”

So whenever the Boilermakers found out about a nonunion outfit coming in to do work, they would line up to apply with all of their certifications, experience and union cards. Cianbro often boasted that its workers also had pensions, health and welfare and other benefits, but after working for the company, McHugh found out workers had to purchase all of those benefits separately.

“I was getting $15 an hour in my paycheck and I would have had to buy a pension, insurance and the other benefits out of that,” he recalled. “In the Boilermakers I was making $18 an hour and already automatically had a pension, an annuity and all those benefits, so I didn’t have to think about it.”

McHugh said whenever he got on a job at a nonunion site he would hold up xeroxed copies of his pension report and annuity to show nonunion workers in an effort to recruit them to join the union. Sometimes he was even able to direct workers to other unions depending on their trade.

“I would show guys who were in their 40s and 50s and they just couldn’t believe the kind of cash we had coming to us when we retired,” he recalled. “We tried to use those things as organizing tools, particularly so we could take their best people from them.”

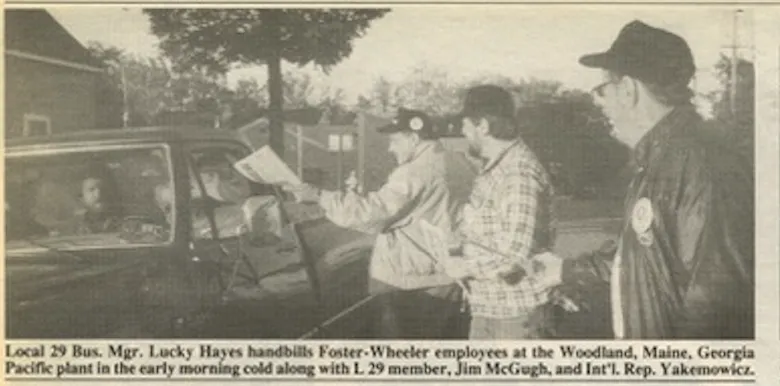

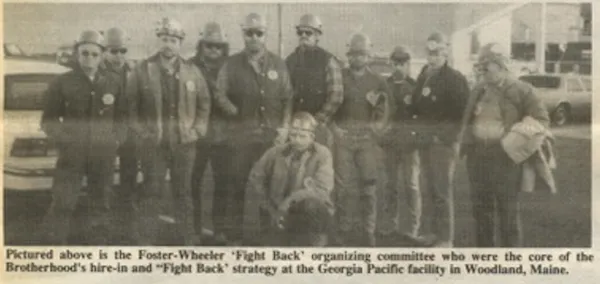

In 1988, Boilermakers 29 had two Fight Back campaigns — one at the Rumford mill and another at the former Georgia-Pacific paper mill in Baileyville. Local 29 members caught wind that boiler contractor Foster-Wheeler, which formerly had contracts with the Boilermakers, was doing a job at the GP mill using nonunion labor. That's when Local 29 set up an informational picket line and called in a union rep named Tony Yakemowicz. The larger-than-life organizer from Pittsburgh carried a ’45 pistol for protection and was known as “a living legend feared by ‘merit shop’ contractors from coast-to-coast.”

“When Tony came up here to give us a hand with this contractor, I never realized just how much he can shake these rat contractors up,” explained Business Manager Lucky Hayes in the union’s newsletter. “But I’ll tell you, Yak can strike fear in their hearts. They know that when he comes to run a Fight Back campaign, it won’t be just business as usual.”

Yakemowicz collected 86 job applications from members, but the company wouldn’t accept them at the gate, so they passed them in at the local employment office. After waiting weeks Local 29 members learned that the man at the employment office never sent in the applications so they made a complaint to the state and the man was transferred to Fort Kent.

“ I don’t think that was a promotion," said McHugh.

After ignoring the applications, Foster Wheeler ended up paying the price with a big fat unfair labor practice slapped on it for discriminating against members of the Brotherhood.

“When this contractor, who we built into one of the most successful boiler contractors in the country, walked away from our labor agreement, business as usual ended,” Yakemowicz was quoted in the union’s newsletter. “Now, for Foster Wheeler, business as usual means a Fight Back campaign on every job they have in the country. We have them targeted nationwide, and they will feel the bite of the Boilermaker’s Fight Back movement until they sign back up.”

Boilermakers field director Connie Mobley agreed.

“I think Foster-Wheeler is getting the message that they aren’t going to get away with just walking away after all we’ve done for them,” said Mobley. “We’re going to reorganize them no matter what it takes. And if the heat puts them out of business, it’s their own fault. But they just ain’t gonna do our work without a fight. And when I say it, they know it’s true.”

While McHugh was not among the members who got a pay out from the Foster Wheeler case because he was already working at the time, he did win wages from the separate campaign at the Rumford mill.

“The point was we cost them money and that was the idea,” he said.

McHugh would later become involved in another Fight Back campaign in 1995 with Cianbro at the Jay mill involving members of building trades unions. In 2009, 50 Boilermakers won a $12 million settlement with the company Fluor Daniel Inc. over the firm’s anti-union hiring practices stemming back to the early 1990s. A total of 167 union members in Kentucky, Louisiana and Arizona received back pay and interest payments ranging from $8,000 to $217,000.

McHugh said he’d like to see more efforts like the Fight Back campaign. Having just turned 73, McHugh says he is very grateful to have his pension and annuity and he wants younger generations of working people to have what he has.

“I’d like to see more of these kinds of Fight Back campaigns happening today,” he said. “With the proliferation of non-union companies, especially in the building trades, I think we should do more to point out the differences between union and non-union work.”